AFRICA

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Consistent

Image: Eduardo Soteras/Getty Images

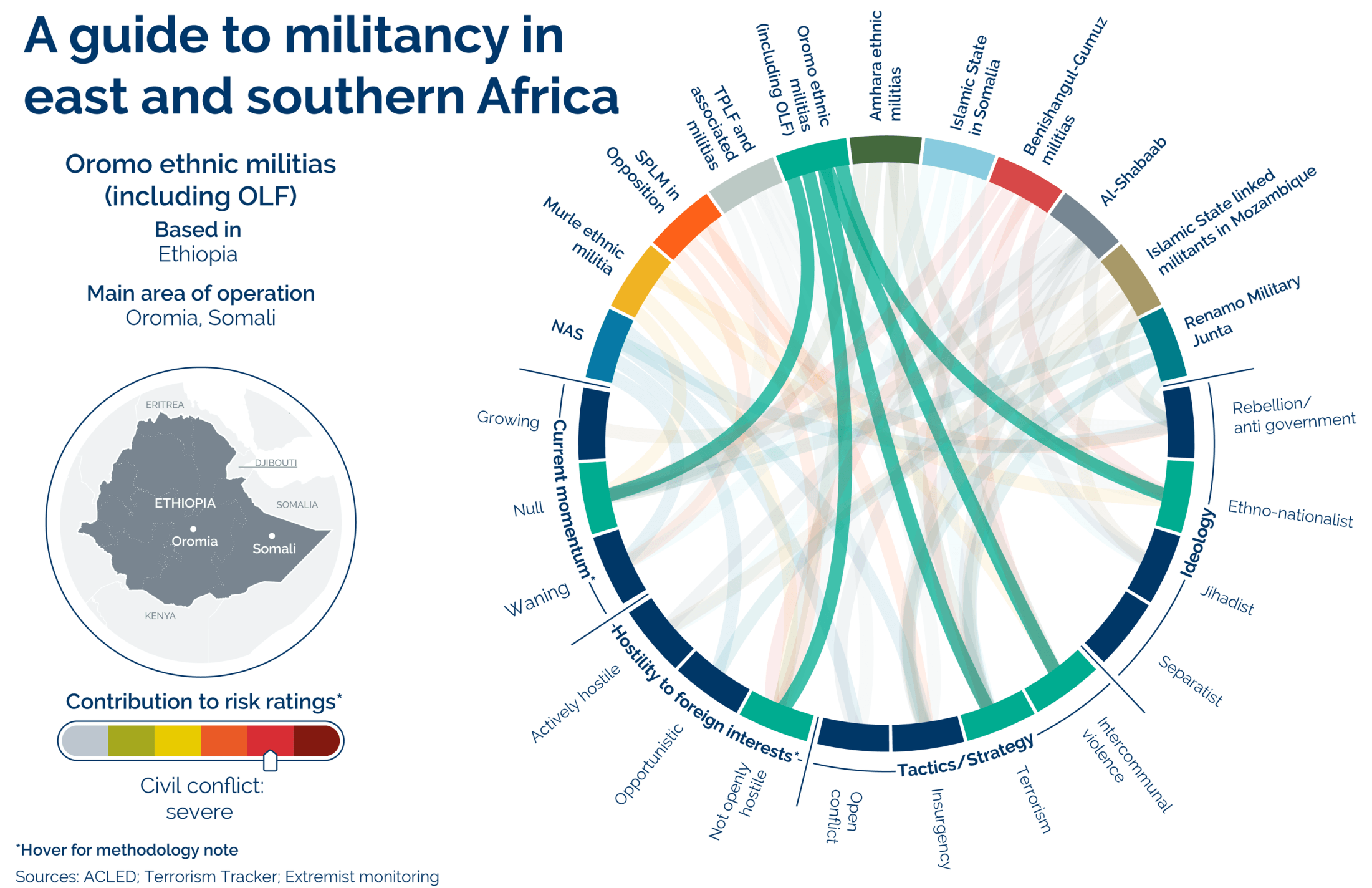

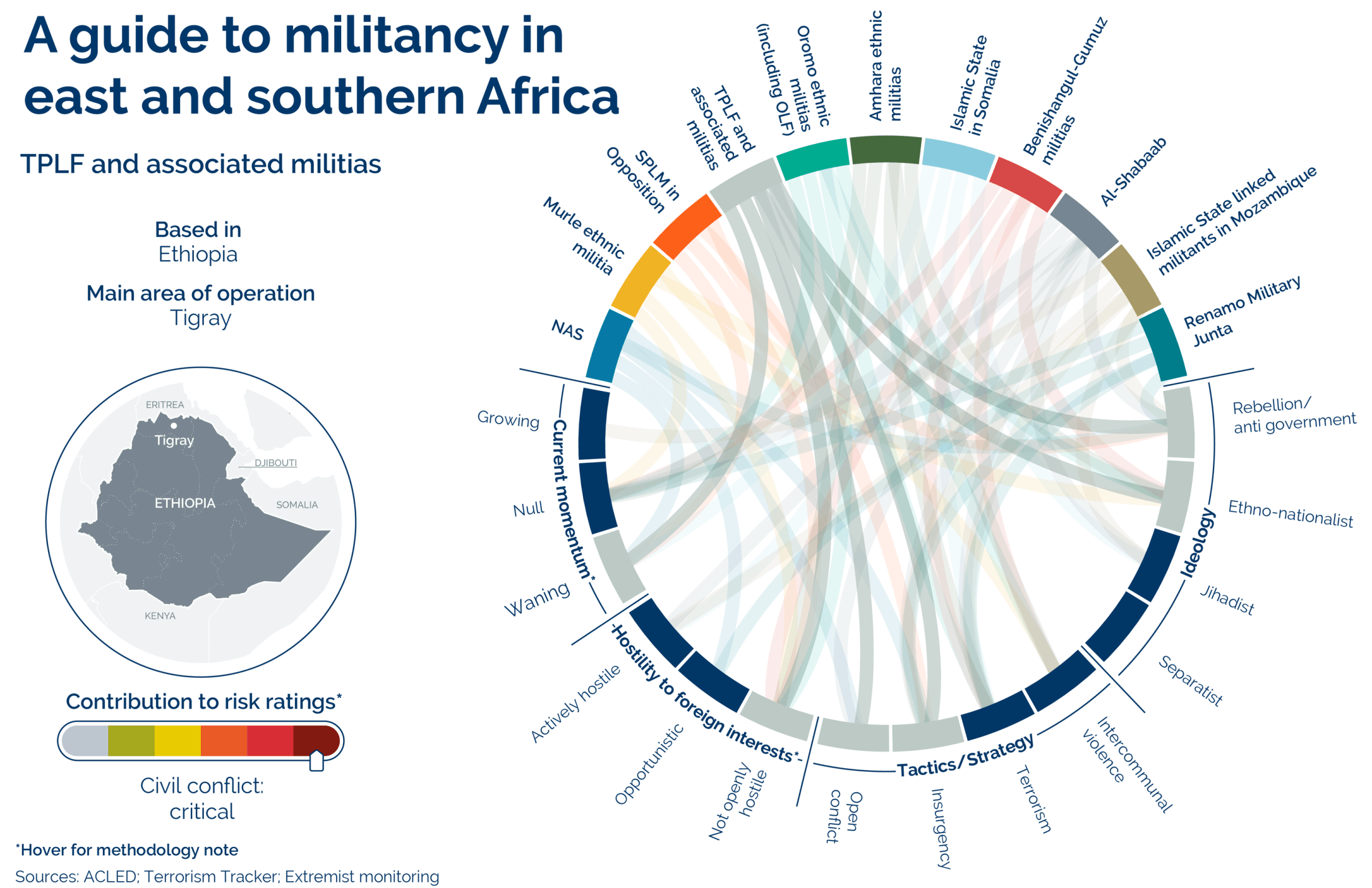

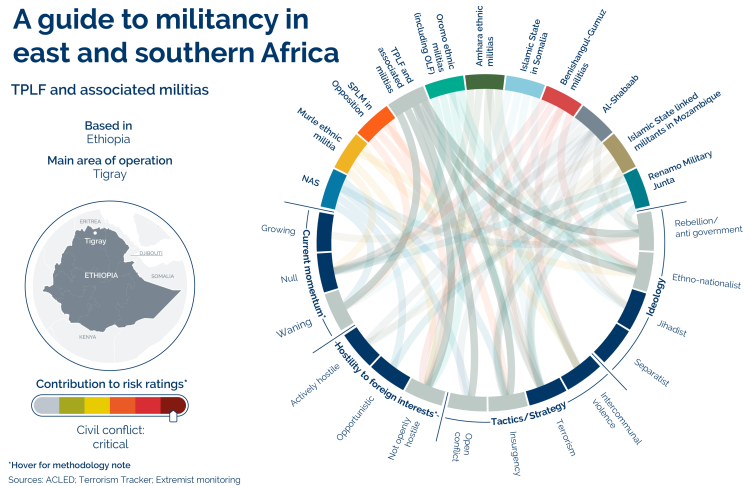

Ethiopia faces the biggest challenges in 2021. After years of rising ethnic and political tensions, the country is now on the cusp of a crisis that has the potential to splinter the country along ethnic lines. A standoff between the federal government and the TPLF has already prompted an armed conflict in the Tigray region. And ethno-nationalist groups elsewhere in the country, many of which the government says are linked to the TPLF, are continuing to mount frequent and widespread violence against civilians.

A general election due in Ethiopia on 5 June is likely to exacerbate ethnic and political tensions, as actors jockey for influence and control ahead of the poll. This will probably take the form of civil unrest and further outbreaks of violence, and potentially also mutinies in the armed forces or even a coup attempt against the prime minister.

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to continue to haunt the region through 2021, both economically and epidemiologically. Most countries will probably be comparatively late to obtain and roll-out vaccines, with widespread inoculations unlikely before 2022. This means that transmission is likely to continue across the continent, although young populations will probably continue to spare many countries the human cost of the virus.

Still, ongoing outbreaks of Covid-19 will probably force governments to implement economy-damaging containment measures, even if they are localised. And these continuing outbreaks will probably mean countries in the region become economically and logistically isolated. This is because widespread vaccination campaigns in advanced economies mean they will probably start to move beyond the pandemic in 2021.

The countries in East & Southern Africa that are most likely to bear the economic brunt of the pandemic in the coming year are Angola, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Economic challenges in these countries will probably unravel support for governments and lead to rising unrest and declines in law and order unless they take action. For several, the inclination will almost certainly be to suppress and contain. We anticipate this will have implications for organisations operating in those countries.

In Zambia, the combination of dire socio-economic conditions and an election scheduled for August leaves President Lungu in a weak position. This will probably push him to try to take greater control, undermine checks and balances, and suppress the popular opposition candidate, Hakainde Hichilema, ahead of the poll. The government’s poor financial position is also likely to mean Mr Lungu is tempted to try to extract more tax from foreign mining companies in Zambia. There is precedent for this: in 2019 the government unilaterally increased royalties by up to 4%.

The Angolan president also faces challenging economic conditions, although we doubt these will lead to political instability. The collapse in oil demand caused by the pandemic in 2020 exacerbated a recession, leaving the country’s economy smaller than it was a decade ago. This will mean the country is liable to sporadic hardship protests, as occurred in 2020. But the opposition is weak and has been unable to capitalise on this discontent. So we doubt demonstrations would evolve into a wider movement.

A deep recession in South Africa and looming reforms are likely to drive disruptive strikes and protests over unemployment, hardship and access to public services in 2021. The impacts of the pandemic will probably both exacerbate the need for, and provide the president with a justification for, much-needed structural reforms in 2021, including at Eskom and other state-owned enterprises. These are likely to be highly contentious with trade unions, many of which wield significant influence among South Africans.

Reform efforts are also likely to deepen splits within South Africa’s governing ANC, as populists and ideologues in the party instead push for more radical changes. Opponents of President Ramaphosa will probably try to weaken his standing ahead of an important party conference in 2022. Despite this, a genuine threat to Mr Ramaphosa’s position seems unlikely. This is largely because – despite South Africa being badly affected by Covid-19 – his position seems to have improved throughout the pandemic. And we doubt his opponents would be able to gain much traction in mobilising public opinion or the governing ANC against him.

Tanzania, Uganda and Mozambique all look reasonably likely to pull through 2021 without too much economic hardship or fallout from the pandemic. But all are likely, as in Zambia, to be challenging operating environments this year.

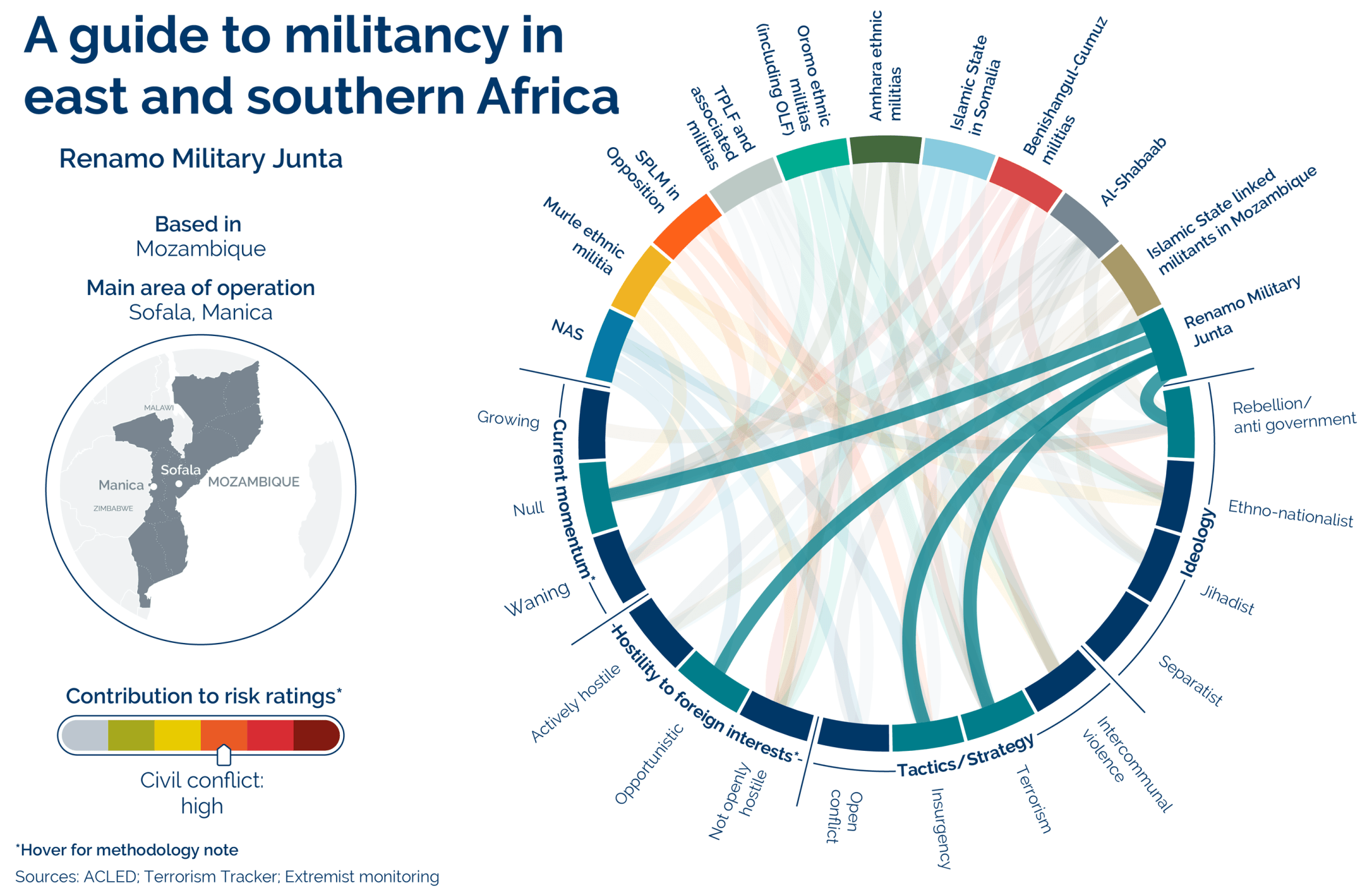

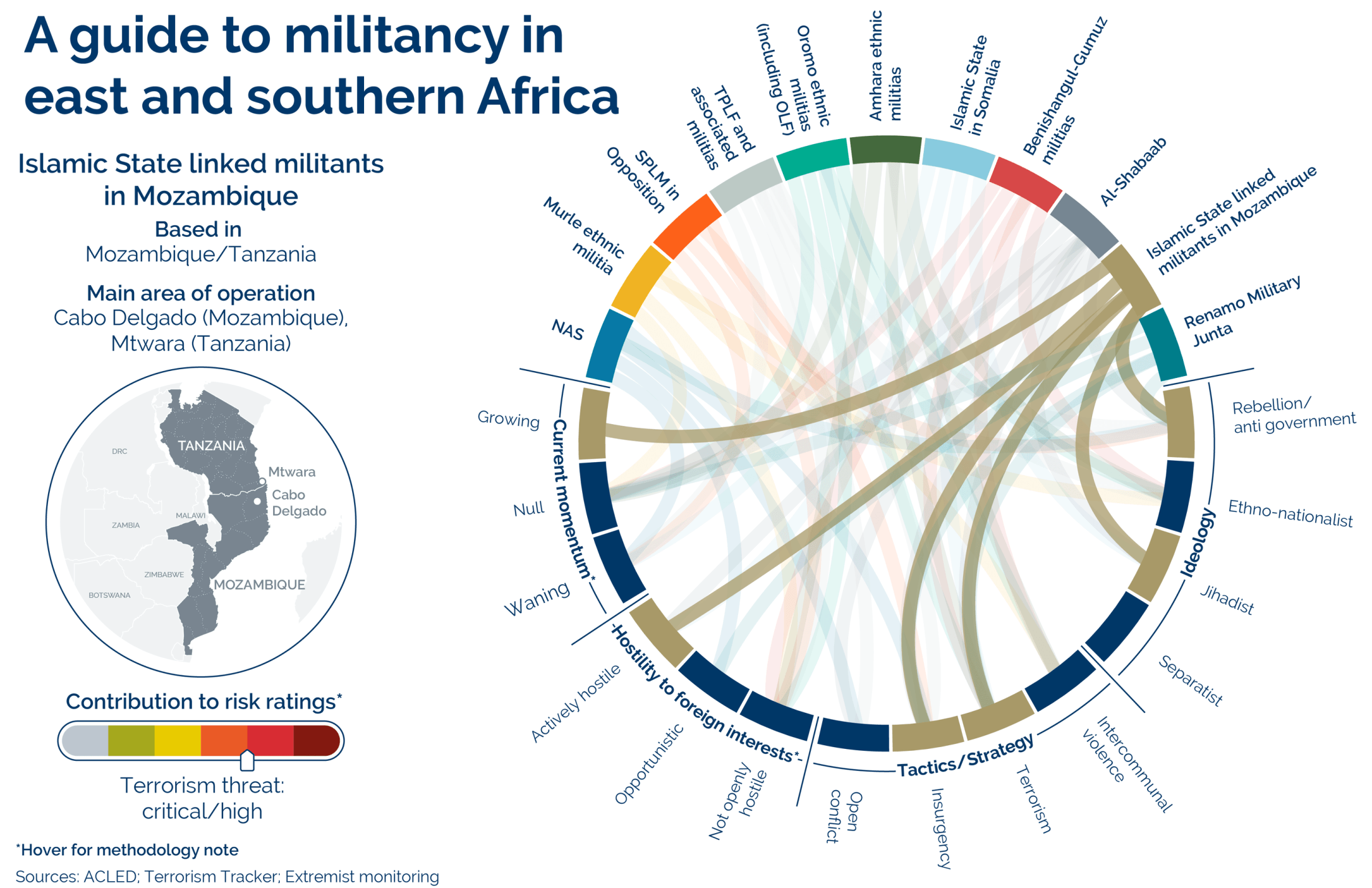

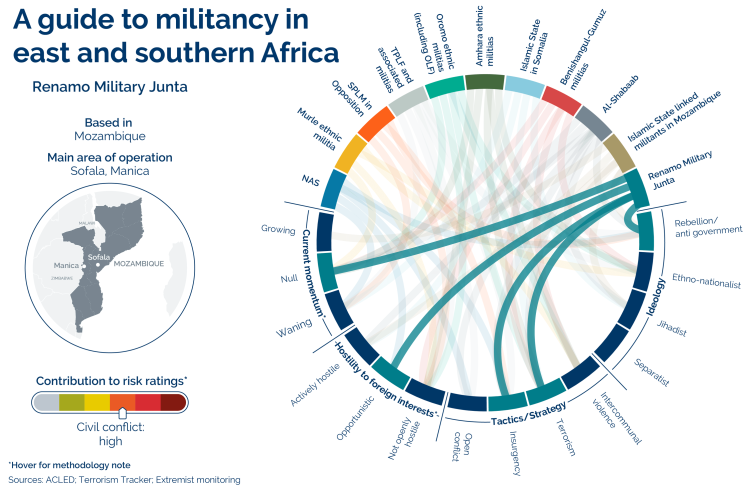

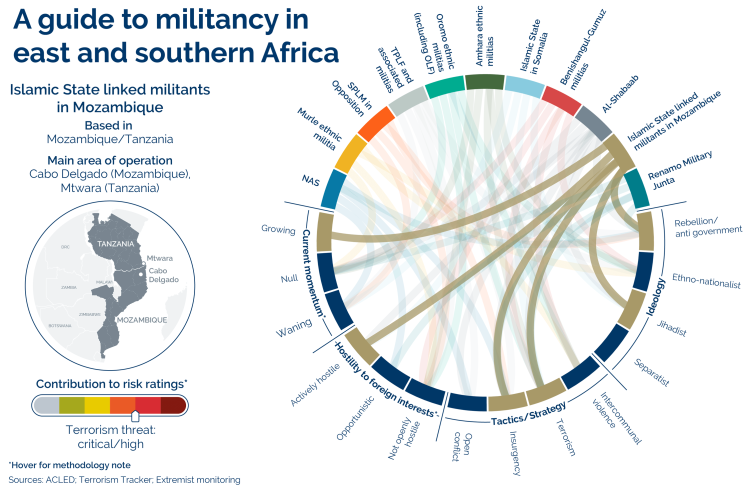

In Mozambique, we anticipate a higher degree of government interference and control in the media and NGO sector in 2021. It is losing control of a jihadist insurgency in the Cabo Delgado province, and it faces renewed attacks by a Renamo splinter group in central provinces. The government has already shown a willingness to interfere in reporting by the media and third sector over violence and humanitarian concerns. And it is likely to ramp up such attempts, amid increasing concerns from gas investors, and allegations of human rights abuses by security forces.

The Tanzanian government will benefit from stable prices for gold and tobacco, its main exports. But the country’s tourism sector, which provides jobs for around 12% of the active workforce, is likely to take a hit. The government has not published Covid-19 data since mid-2020 and has faced accusations of covering up the extent of an outbreak there. This is likely to dampen confidence in the country, and mean foreign visitors and tourism firms are reluctant to return to the country.

Although the broader outlook for Uganda is positive, an election due in January will probably be a flashpoint for instability. The authorities have started to restrict political space for the opposition, and particularly for Bobi Wine, a popular politician who will be challenging President Museveni at the poll. Repression is likely to intensify next year, with the continued arrest of supporters and confidantes of Wine being a flashpoint for unrest. This seems unlikely to be enough to challenge the government, however.

Kenya faces a relatively smooth 2021. A positive growth outlook for the year will probably enable it to sustain a larger debt burden resulting from the pandemic. In our estimation, the main threat to stability stems from increasing political competition before a presidential election in 2022. Jockeying ahead of the poll has the potential to undermine a fragile balance of interests between ethnic groups, making unrest and communal violence a reasonable possibility. But we doubt this would be widespread.

Ongoing outbreaks of Covid-19 will probably force governments to implement economy-damaging containment measures, even if they are localised.

In Mozambique, we anticipate a higher degree of government interference and control in the media and NGO sector in 2021.

Image: Eduardo Soteras/Getty Images

Image: Marco Longari/Getty Images

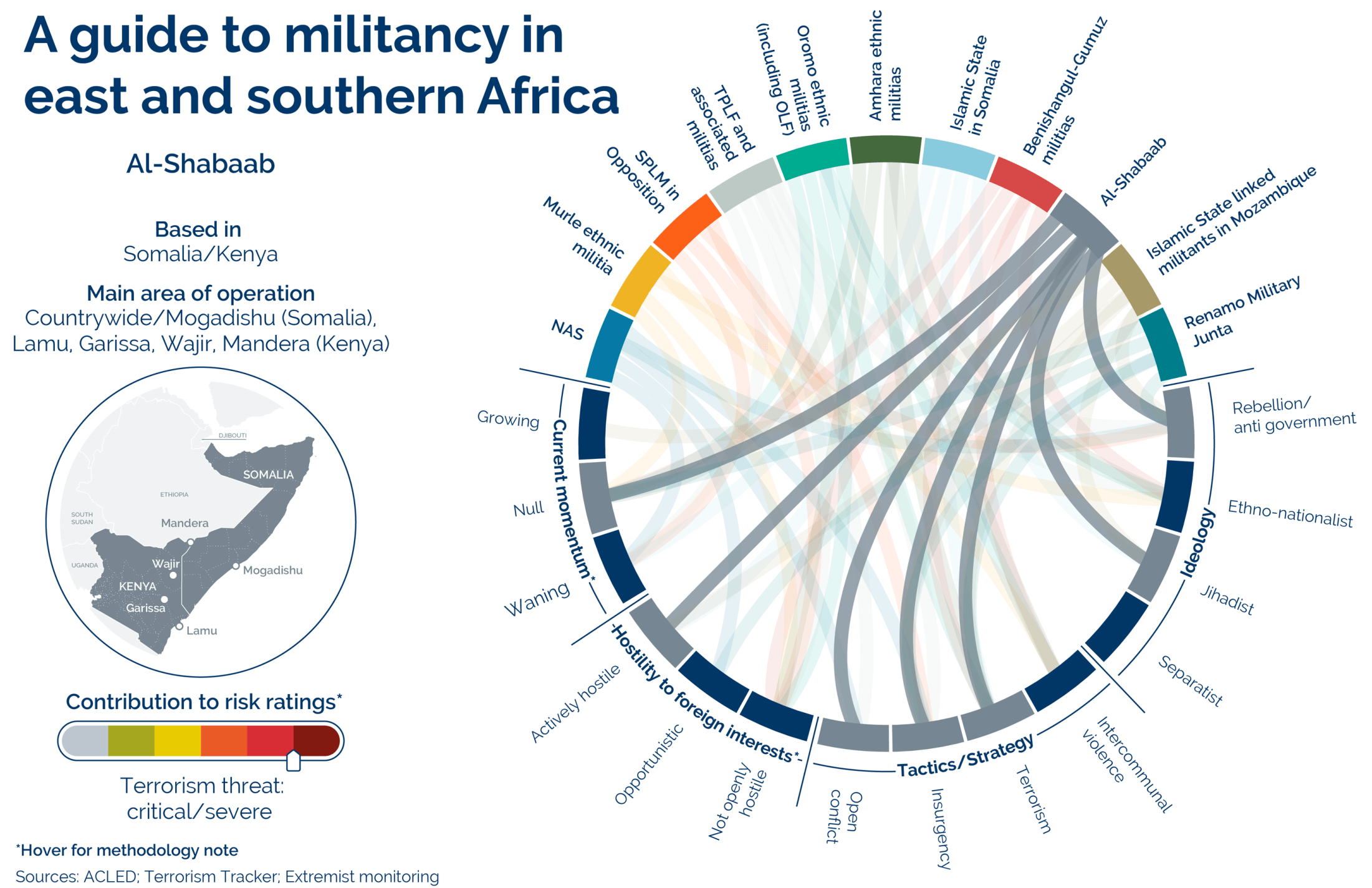

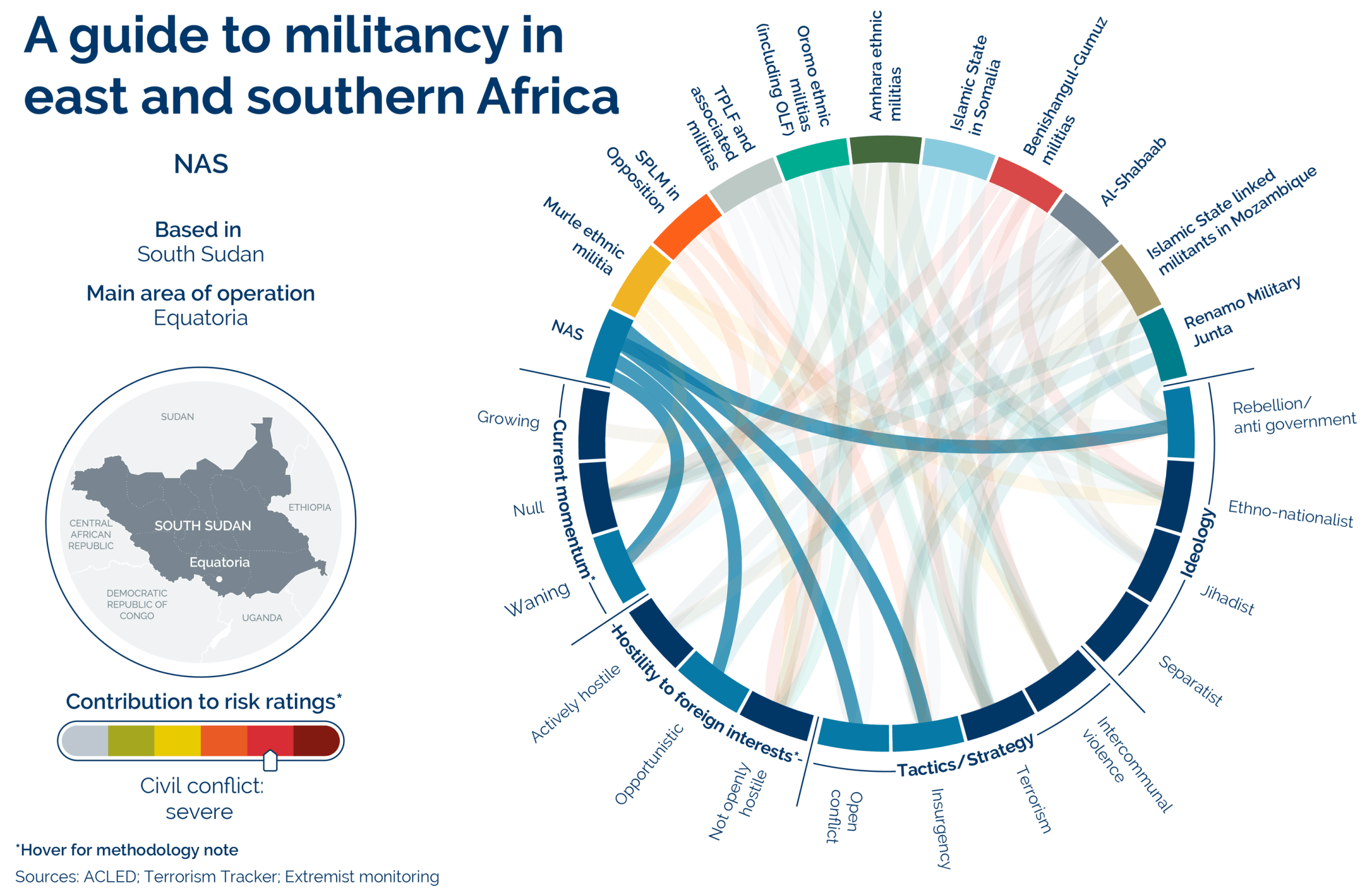

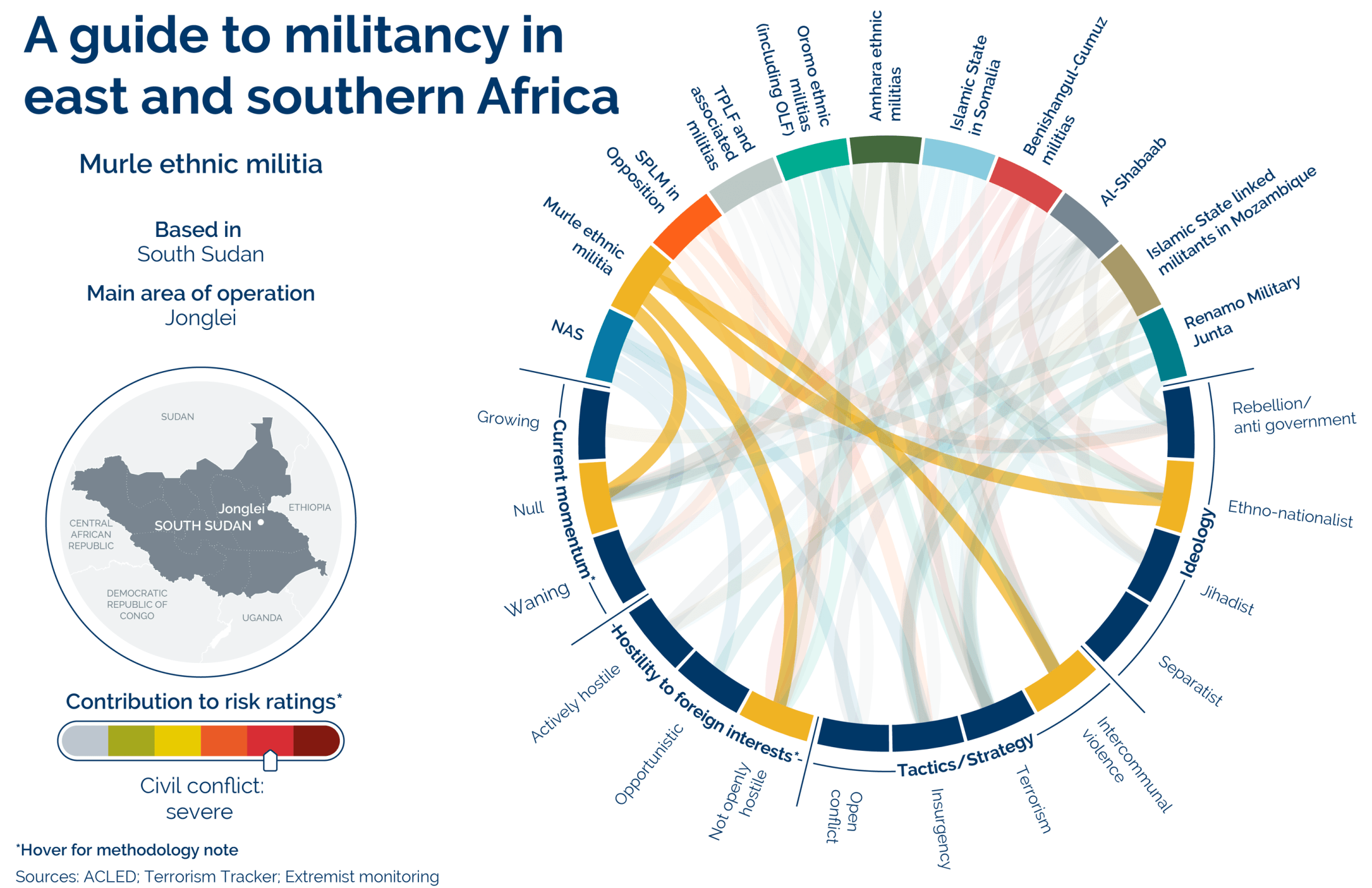

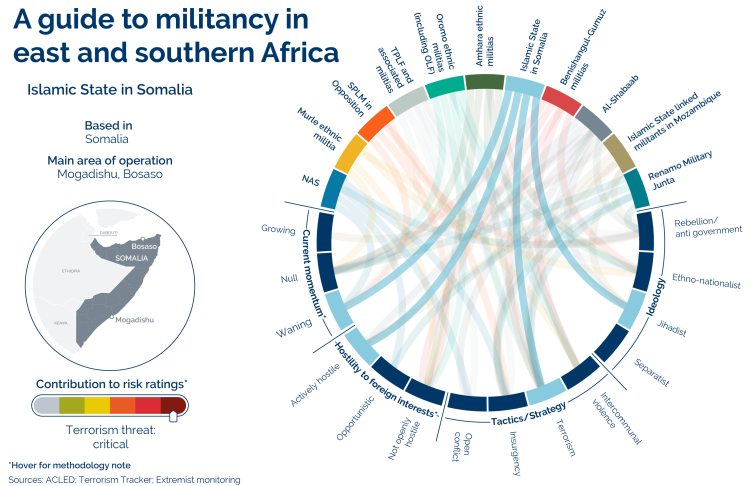

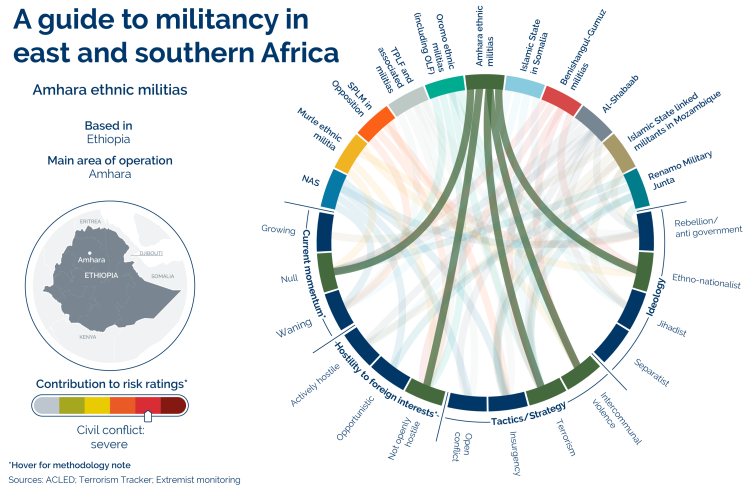

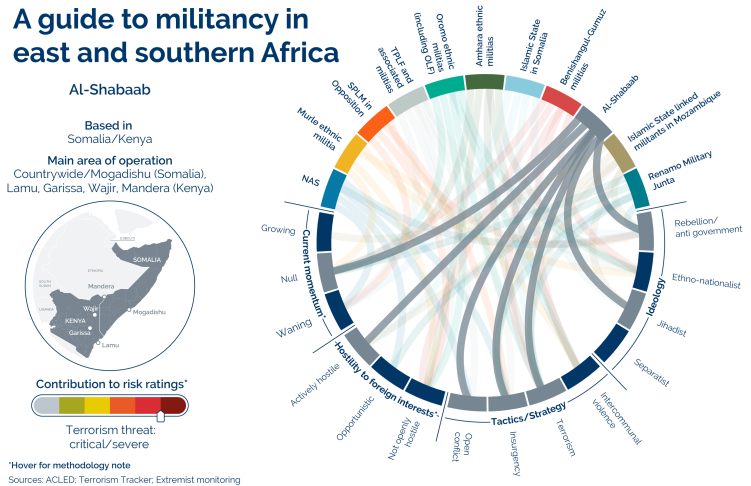

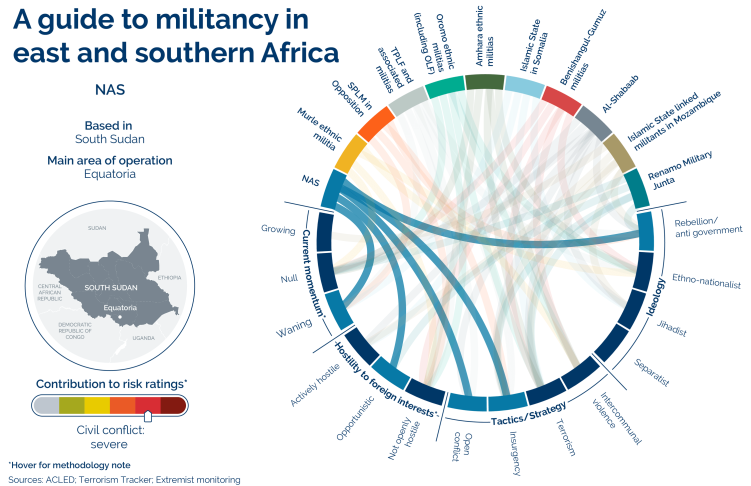

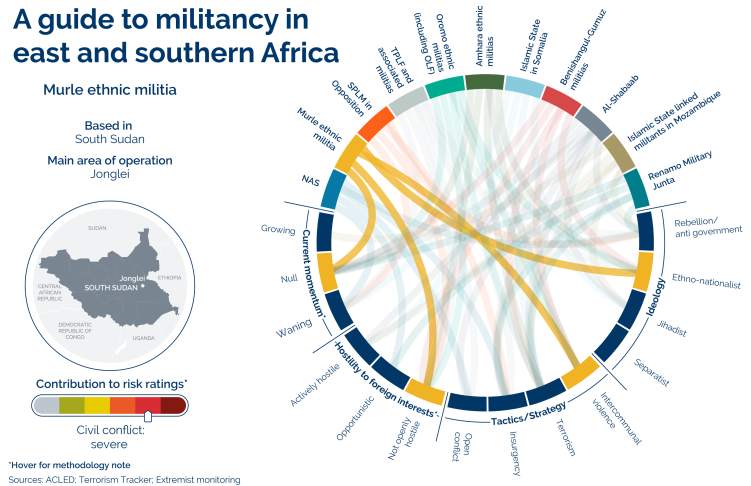

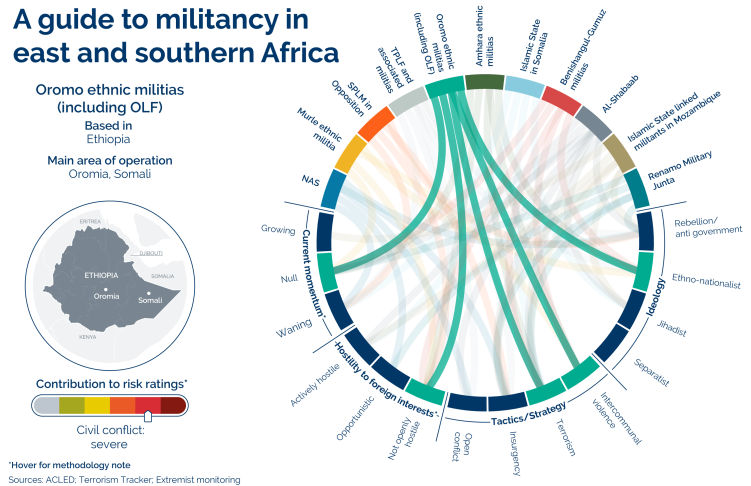

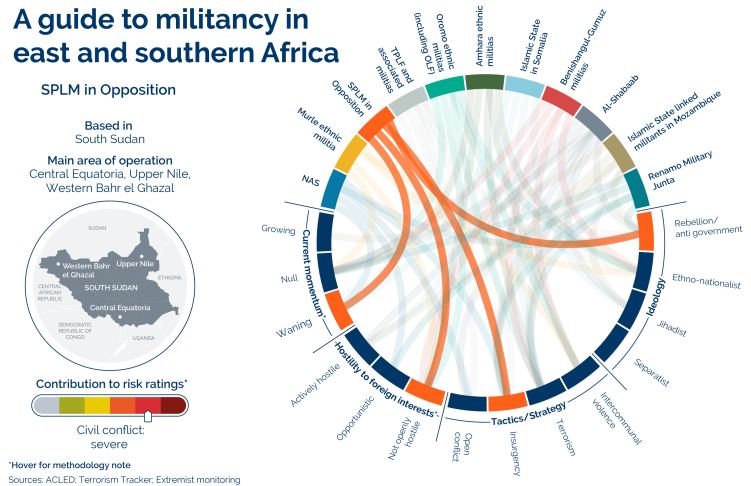

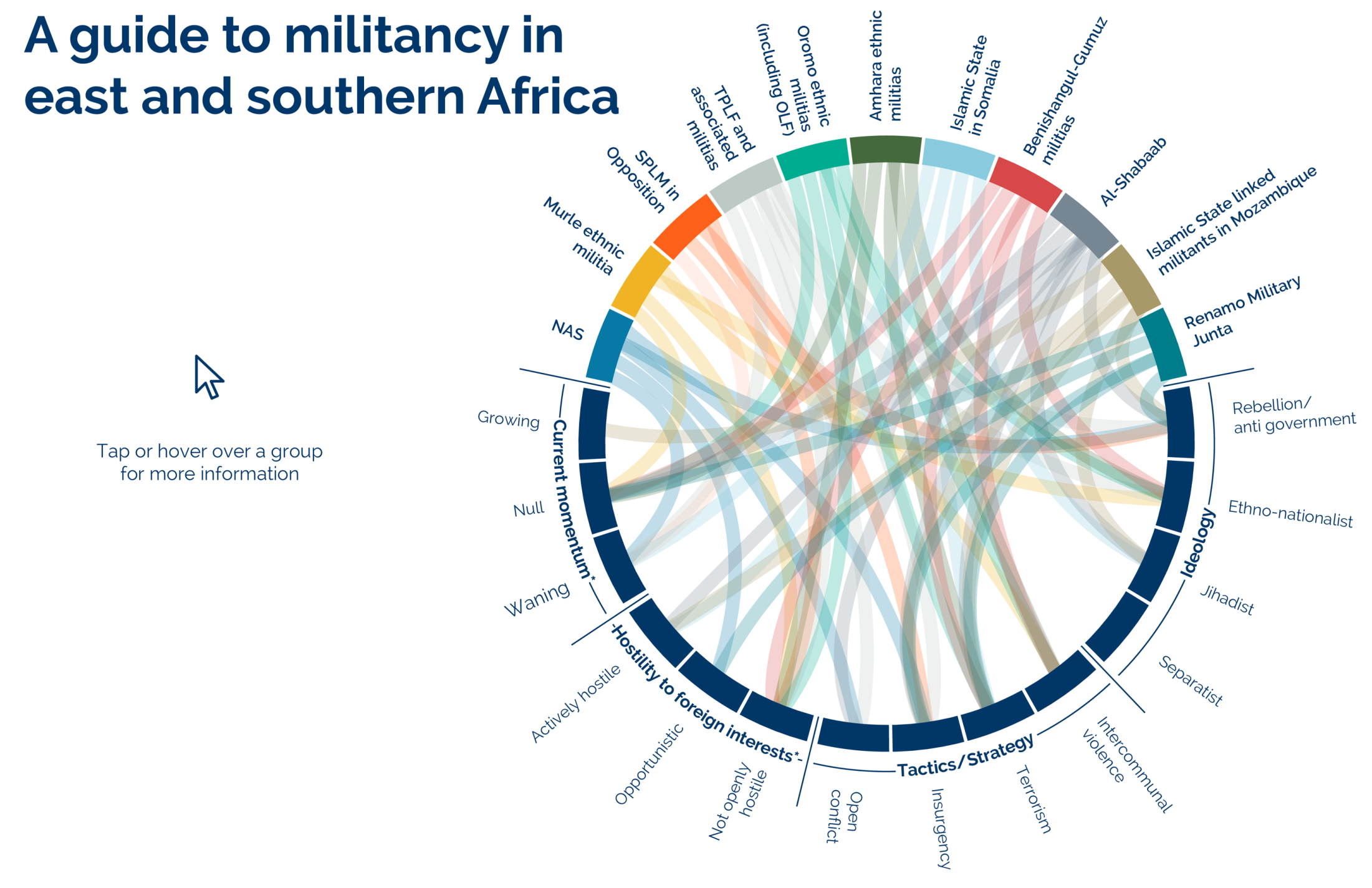

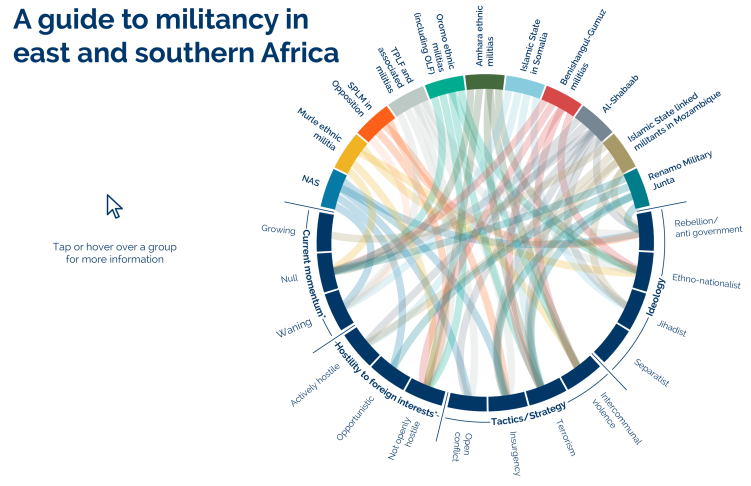

Risk Advisory TerorrismTracker and extremism monitoring

Forecasts

A brief security crisis around contested elections is highly likely in Uganda this year. The opposition has formed an alliance to challenge President Museveni at the poll. This is unlikely to directly threaten the incumbent, whose NRM party benefits from broad popular appeal in rural areas. But the young, urban opposition will probably reject the outcome of the vote and organise protests that are liable to turn violent. These would probably occur in cities, including Kampala, as well as Jinja, Gomba and Busia, where the opposition is popular. None of which is likely to alter the outcome of the vote.

A controversial election in Uganda

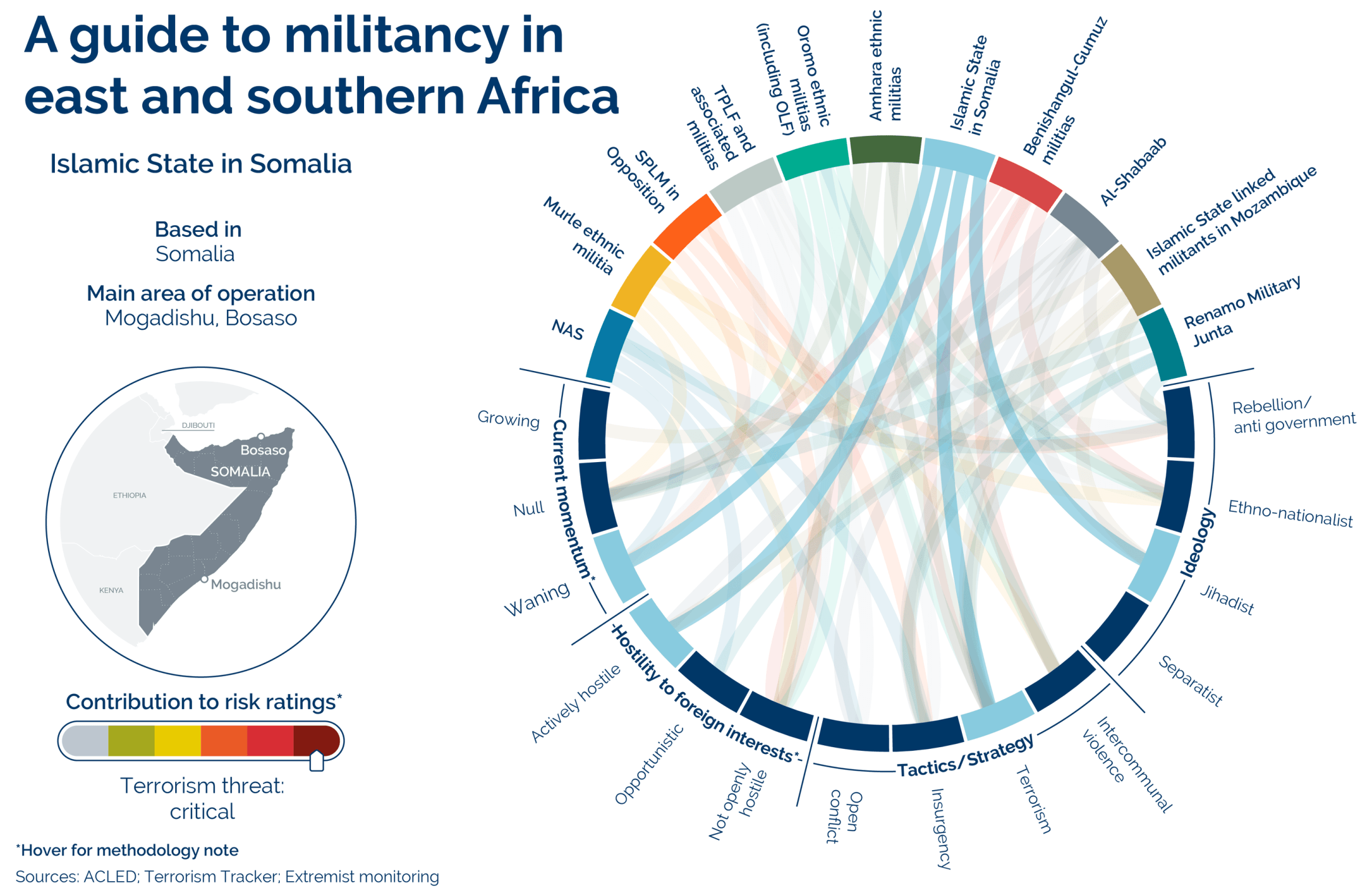

The Mozambican authorities are unlikely to make significant progress in countering a jihadist insurgency in Cabo Delgado province in 2021. Local militants are markedly more organised and bolder than in previous years, and we anticipate that they will continue to challenge the government for control of small towns, and expand beyond the province into border areas of southern Tanzania. But despite Islamic State making threats against regional countries, long-range terrorist attacks in Maputo, Dar es Salaam or even South Africa are unlikely.

Worsening security in northern Mozambique

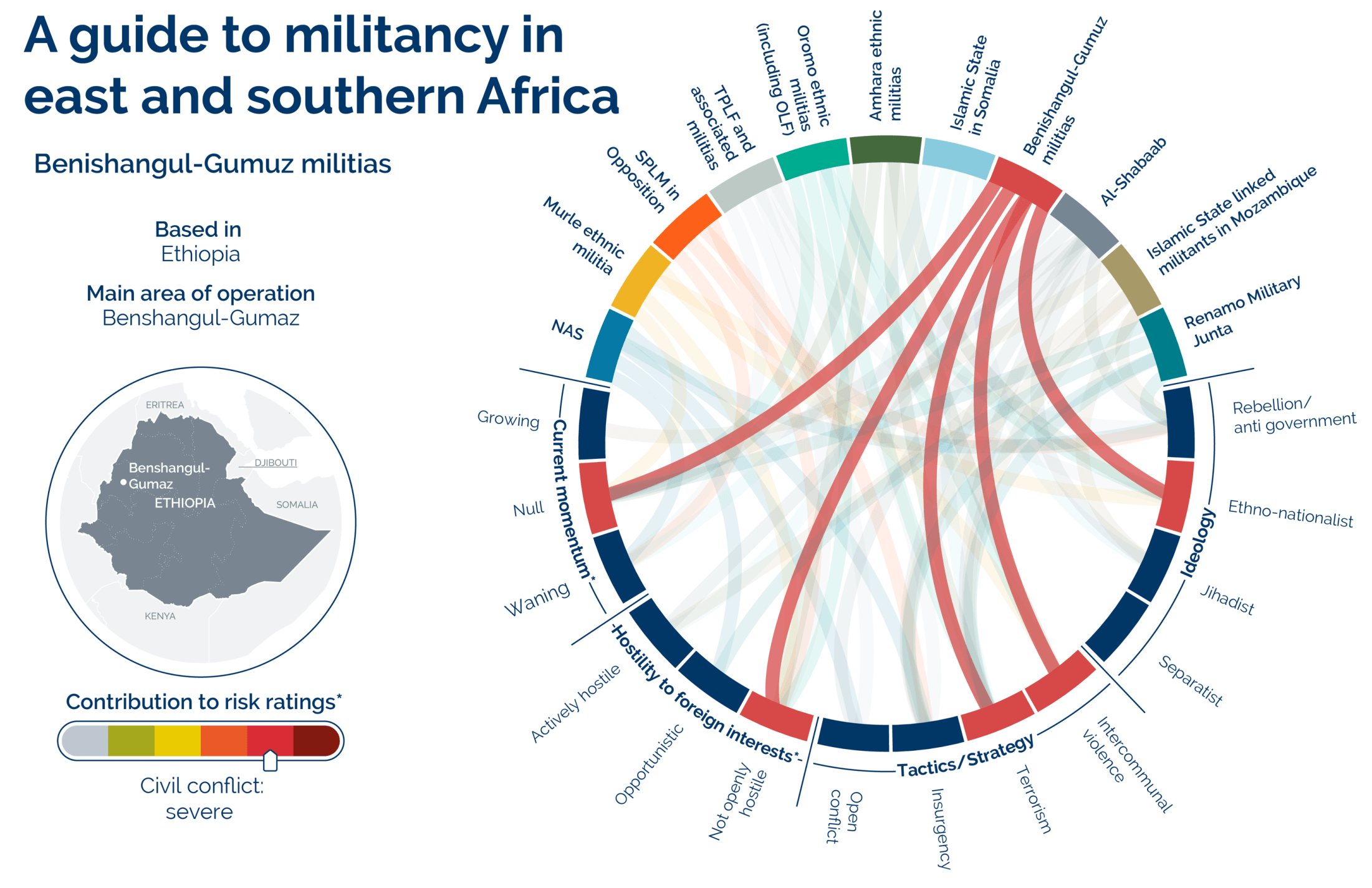

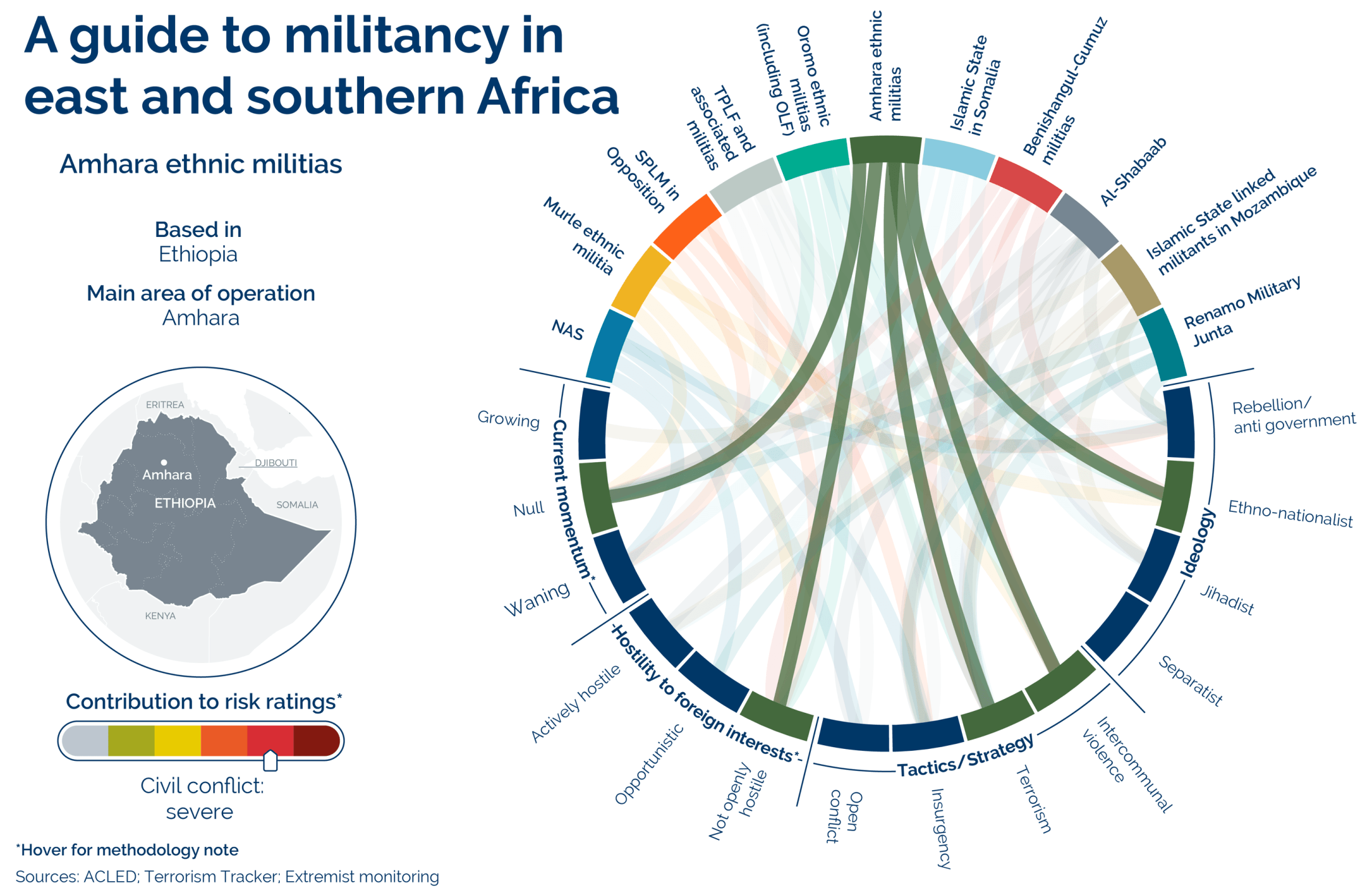

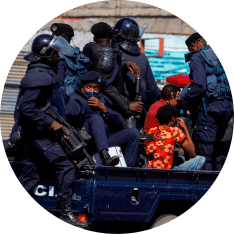

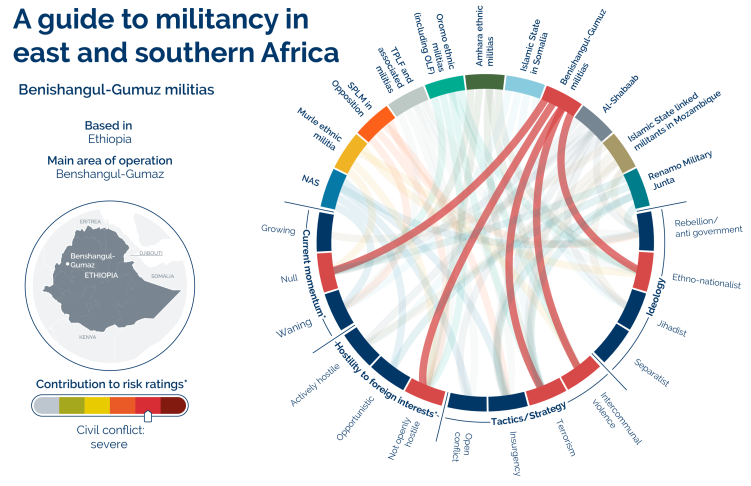

Pockets of civil conflict will almost certainly continue in Ethiopia throughout 2021. The security implications of this will probably be worst in the northern Tigray region, where the well-armed TPLF group is highly likely to mount an insurgency against federal forces. Conflict in other parts of the country will probably be more asymmetric. Armed ethnic militias have frequently mounted attacks against security forces and civilians in parts of Benishangul-Gumuz, Amhara and Oromia in the past few years. While federal and local forces are unlikely to have the capacity to contain this, such violence will probably remain highly targeted.

War in ethiopia

Forecasts

Angola

Botswana

Burundi

Eritrea

eSwatini

Ethiopia

Kenya

Lesotho

Madagascar

Malawi

Mauritius

Mozambique

Namibia

Rwanda

South Africa

Seychelles

South Sudan

Tanzania

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Outliers

War between Rwanda and Uganda

Monitoring Points

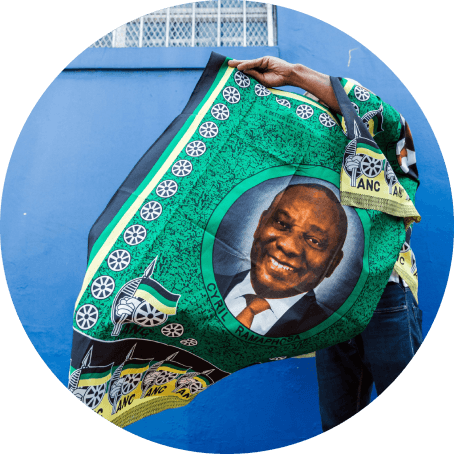

Government instability in South Africa

Factionalism in the ANC is a key indicator for government stability in South Africa. Populists in the ANC are likely to try to undermine President Ramaphosa ahead of the all-important ANC party conference in 2022, where Mr Ramaphosa will face election for his second full term as party leader. And so throughout 2021, populist allies of the former president, Jacob Zuma, and the ANC secretary-general, Ace Magashule, will probably try to challenge the president. This will probably be on policies related to the national electricity provider Eskom as well as post-pandemic economic recovery plans.

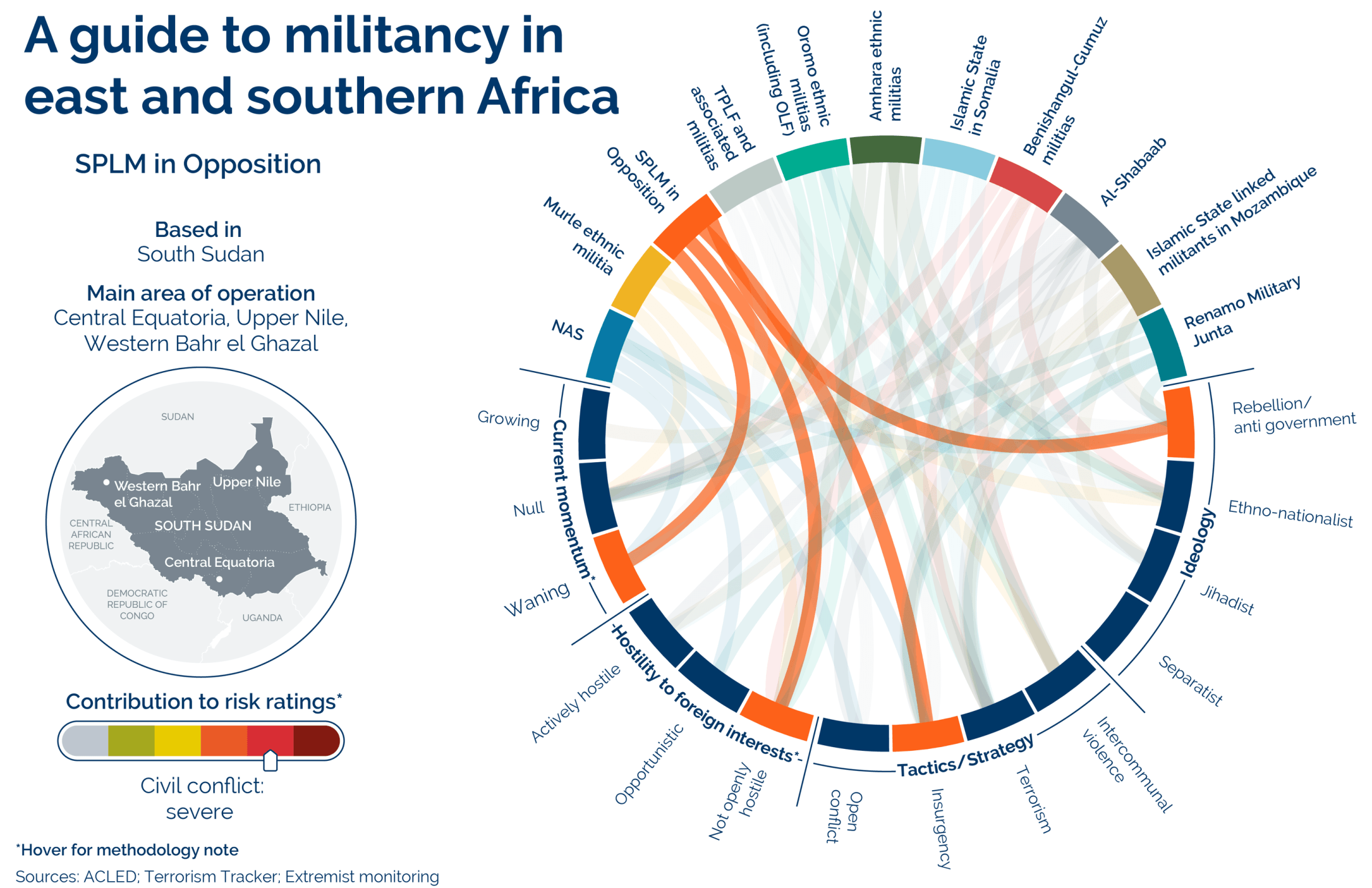

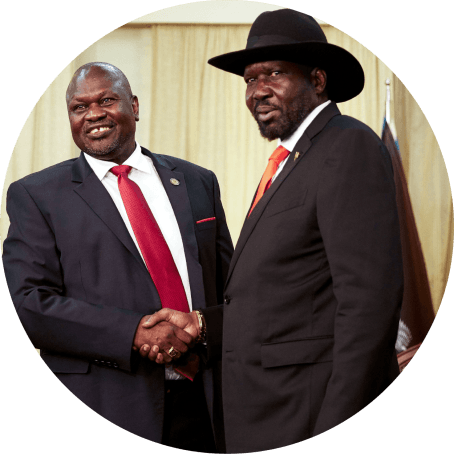

Simmering tensions in South Sudan

Political disagreements between the parties to a peace deal signed in 2018 would indicate a potential breakdown of the agreement and a return to conflict. A three-year transitional period means a presidential election is not due until 2023. But members of the unity government may try to push for a vote sooner, particularly if they feel they lack substantial influence in government. The integration of former rebels into the army and disarmament of militias seems likely to prompt disagreements and clashes.

Ethno-nationalism in Ethiopia

Ethnicity is likely to colour politics and security in Ethiopia through 2021. We anticipate that the government will continue to clamp down on ethno-nationalist groups ahead of an election due on 5 June. This will be a flashpoint for disruptive and violent protests: the ongoing trial of Oromo opposition leader Jawar Mohammed on terrorism charges will be a key event to watch. Efforts to suppress ethno-nationalists will probably undermine the faith that opponents of the government have in the poll in June. And so rather than prevent ethnically-motivated violence, they are more likely to sustain unrest in the coming year.

Images: Luke Dray; Osvaldo Silva; AFP Contributor; Eduardo Soteras; Maheder Haileselassie Tadese; Alex Mcbride/Getty Images

AFRICA

Overall trend: Consistent

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Image: Eduardo Soteras/Getty Images

Ethiopia faces the biggest challenges in 2021. After years of rising ethnic and political tensions, the country is now on the cusp of a crisis that has the potential to splinter the country along ethnic lines. A standoff between the federal government and the TPLF has already prompted an armed conflict in the Tigray region. And ethno-nationalist groups elsewhere in the country, many of which the government says are linked to the TPLF, are continuing to mount frequent and widespread violence against civilians.

A general election due in Ethiopia on 5 June is likely to exacerbate ethnic and political tensions, as actors jockey for influence and control ahead of the poll. This will probably take the form of civil unrest and further outbreaks of violence, and potentially also mutinies in the armed forces or even a coup attempt against the prime minister.

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to continue to haunt the region through 2021, both economically and epidemiologically. Most countries will probably be comparatively late to obtain and roll-out vaccines, with widespread inoculations unlikely before 2022. This means that transmission is likely to continue across the continent, although young populations will probably continue to spare many countries the human cost of the virus.

Still, ongoing outbreaks of Covid-19 will probably force governments to implement economy-damaging containment measures, even if they are localised. And these continuing outbreaks will probably mean countries in the region become economically and logistically isolated. This is because widespread vaccination campaigns in advanced economies mean they will probably start to move beyond the pandemic in 2021.

The countries in East & Southern Africa that are most likely to bear the economic brunt of the pandemic in the coming year are Angola, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Economic challenges in these countries will probably unravel support for governments and lead to rising unrest and declines in law and order unless they take action. For several, the inclination will almost certainly be to suppress and contain. We anticipate this will have implications for organisations operating in

those countries.

In Zambia, the combination of dire socio-economic conditions and an election scheduled for August leaves President Lungu in a weak position. This will probably push him to try to take greater control, undermine checks and balances, and suppress the popular opposition candidate, Hakainde Hichilema, ahead of the poll. The government’s poor financial position is also likely to mean Mr Lungu is tempted to try to extract more tax from foreign mining companies in Zambia. There is precedent for this: in 2019 the government unilaterally increased royalties by up to 4%.

The Angolan president also faces challenging economic conditions, although we doubt these will lead to political instability. The collapse in oil demand caused by the pandemic in 2020 exacerbated a recession, leaving the country’s economy smaller than it was a decade ago. This will mean the country is liable to sporadic hardship protests, as occurred in 2020. But the opposition is weak and has been unable to capitalise on this discontent. So we doubt demonstrations would evolve into a wider movement.

A deep recession in South Africa and looming reforms are likely to drive disruptive strikes and protests over unemployment, hardship and access to public services in 2021. The impacts of the pandemic will probably both exacerbate the need for, and provide the president with a justification for, much-needed structural reforms in 2021, including at Eskom and other state-owned enterprises. These are likely to be highly contentious with trade unions, many of which wield significant influence among South Africans.

Reform efforts are also likely to deepen splits within South Africa’s governing ANC, as populists and ideologues in the party instead push for more radical changes. Opponents of President Ramaphosa will probably try to weaken his standing ahead of an important party conference in 2022. Despite this, a genuine threat to Mr Ramaphosa’s position seems unlikely. This is largely because – despite South Africa being badly affected by Covid-19 – his position seems to have improved throughout the pandemic. And we doubt his opponents would be able to gain much traction in mobilising public opinion or the governing ANC against him.

Image: Eduardo Soteras/Getty Images

Ongoing outbreaks of Covid-19 will probably force governments to implement economy-damaging containment measures, even if they are localised.

Image: Marco Longari/Getty Images

Risk Advisory TerorrismTracker and extremism monitoring

Forecasts

Pockets of civil conflict will almost certainly continue in Ethiopia throughout 2021. The security implications of this will probably be worst in the northern Tigray region, where the well-armed TPLF group is highly likely to mount an insurgency against federal forces. Conflict in other parts of the country will probably be more asymmetric. Armed ethnic militias have frequently mounted attacks against security forces and civilians in parts of Benishangul-Gumuz, Amhara and Oromia in the past few years. While federal and local forces are unlikely to have the capacity to contain this, such violence will probably remain highly targeted.

War in ethiopia

A brief security crisis around contested elections is highly likely in Uganda this year. The opposition has formed an alliance to challenge President Museveni at the poll. This is unlikely to directly threaten the incumbent, whose NRM party benefits from broad popular appeal in rural areas. But the young, urban opposition will probably reject the outcome of the vote and organise protests that are liable to turn violent. These would probably occur in cities, including Kampala, as well as Jinja, Gomba and Busia, where the opposition is popular. None of which is likely to alter the outcome of the vote.

A controversial election in Uganda

The Mozambican authorities are unlikely to make significant progress in countering a jihadist insurgency in Cabo Delgado province in 2021. Local militants are markedly more organised and bolder than in previous years, and we anticipate that they will continue to challenge the government for control of small towns, and expand beyond the province into border areas of southern Tanzania. But despite Islamic State making threats against regional countries, long-range terrorist attacks in Maputo, Dar es Salaam or even South Africa are unlikely.

Worsening security in northern Mozambique

Angola

Botswana

Burundi

Eritrea

eSwatini

Ethiopia

Kenya

Lesotho

Madagascar

Malawi

Mauritius

Mozambique

Namibia

Rwanda

South Africa

Seychelles

South Sudan

Tanzania

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Outliers

War between Rwanda and Uganda

Monitoring Points

Government instability in South Africa

Simmering tensions in South Sudan

Factionalism in the ANC is a key indicator for government stability in South Africa. Populists in the ANC are likely to try to undermine President Ramaphosa ahead of the all-important ANC party conference in 2022, where Mr Ramaphosa will face election for his second full term as party leader. And so throughout 2021, populist allies of the former president, Jacob Zuma, and the ANC secretary-general, Ace Magashule, will probably try to challenge the president. This will probably be on policies related to the national electricity provider Eskom as well as post-pandemic economic recovery plans.

Ethno-nationalism in Ethiopia

Ethnicity is likely to colour politics and security in Ethiopia through 2021. We anticipate that the government will continue to clamp down on ethno-nationalist groups ahead of an election due on 5 June. This will be a flashpoint for disruptive and violent protests: the ongoing trial of Oromo opposition leader Jawar Mohammed on terrorism charges will be a key event to watch. Efforts to suppress ethno-nationalists will probably undermine the faith that opponents of the government have in the poll in June. And so rather than prevent ethnically-motivated violence, they are more likely to sustain unrest in the coming year.

Political disagreements between the parties to a peace deal signed in 2018 would indicate a potential breakdown of the agreement and a return to conflict. A three-year transitional period means a presidential election is not due until 2023. But members of the unity government may try to push for a vote sooner, particularly if they feel they lack substantial influence in government. The integration of former rebels into the army and disarmament of militias seems likely to prompt disagreements and clashes.

Images: Luke Dray; Osvaldo Silva; AFP Contributor; Eduardo Soteras; Maheder Haileselassie Tadese; Alex Mcbride/Getty Images