CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Consistent

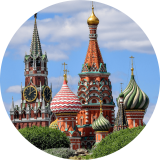

Image: Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

President Erdogan and President Putin start the year with a remarkably positive relationship. This is despite them backing opposing sides in now three wars: Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria. This is proof of their ability to compartmentalise foreign policy issues. And Erdogan and Putin are very unlikely to seek a military conflict in 2021. But the Black Sea and northern Syria are areas where competition between Russia and Turkey risks spilling over into diplomatic hostility this year.

Turkey and Russia will probably strive for greater sway in the Black Sea in 2021, pushing up operational risks for maritime traffic. The Kremlin has rejected all agreements on mutual use of the sea. This stance will jar with Turkish efforts to reassert its naval position after it found gas fields there in 2020. But the military balance has shifted in Russia’s favour. And as in the Sea of Azov in recent years, Russian vessels will probably disrupt shipping to establish Russia as the dominant force. This would potentially include inspections and short-notice naval drills rather than any aggressive activity towards commercial vessels.

Turkey would very likely deploy its navy to the Black Sea to check such behaviour, including naval escorts for its shipping. The sea is large enough to accommodate deployments from both, as well as NATO, and so this would not necessarily push up the likelihood of a military escalation. Unlike in the eastern Mediterranean, there is no urgency on either side to confirm its status as the dominant power. But we forecast that the sea will be a source of fluctuating tensions between Russia and Turkey next year, and a bellwether for their ability to maintain a pragmatic relationship.

The eastern Mediterranean will draw speculation as a conflict risk in 2021, but we think misleadingly. NATO pressure on Turkey and Greece to ease military tensions is working. Both cancelled naval drills in late 2020 to allow for talks. We forecast that Turkey and Greece will keep tensions high with gas exploration missions and naval deployments. But this will be mostly artificial. Turkey seems intent on muscling into regional energy planning, while Greece appears focused on forcing EU sanctions on its neighbour. As such, neither is likely to see a military confrontation as within their interests.

We forecast resurgent US pressure on Turkey and Russia in 2021, with the Biden administration seeking to reassert the US-led rules-based order. Tougher sanctions on Turkey over its purchase of S-400 and on Russia over its cyber activity abroad are likely. This will complicate the risks that Western businesses face in Eurasia. We forecast product boycotts and blacklisting becoming more frequent as both governments resist Western diplomatic pressure. Erdogan has put this tactic to use against France and the US, pushing up reputational risks.

These geopolitical tensions between Russia and Turkey will play out in addition to several existing potential crises in Eurasia this year. Belarus and Kyrgyzstan enter the year in a state of flux, with very unstable regimes. Persistent protests since President Lukashenka rigged his re-election last year have weakened his position, and he will probably initiate a power transition this year. The opposition will probably see this as an opportunity to restart their protest campaign, risking further unrest amid another crackdown by the

security forces.

We are flagging Ukraine as one to watch for regime instability in 2021. President Zelensky’s failure to implement structural reforms and tackle Covid-19 has undermined his public support and highlighted the weakness of state institutions. He also lacks a plan to end the conflict in Donbas, a campaign promise. A rushed resolution – or one that the public deems to be a concession to Russia – would make widespread unrest likely. This has the potential to coincide with anger over state-level corruption and stagnant economic conditions this year, potentially forcing the president to step down.

In Central Asia, the operating environment for businesses looks likely to worsen in 2021 amid sliding rule of law and wider regime instability. Acting President Japarov of Kyrgyzstan, who took office after being sprung from jail, has begun consolidating his power, threatening media freedom in particular. And much of his nationalist political capital is built on resisting foreign ownership in the resources sector. Evidence of abuse of power or state-level corruption scandals would be very likely to prompt his rivals to instigate further unrest and demand that he step down.

Bouts of civil unrest are likely to emerge in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan this year. Covid-19 has strained the social contract that has been in place in those countries since the 1990s: improving living standards and stability with limited freedoms. Food shortages and rising prices are the primary trigger for protests in both. These would be unlikely to threaten regime stability themselves. But a perception among the elite that such insurrection threatens their positions would probably bring them to move against their presidents.

Worsening security in central Asia will challenge Russia and China as the key security and economic partners in the region. Unrest will probably force China to demand greater security assurances to its investment, or insist on providing its own as is already the case in southern Tajikistan. Opposition figures taking power in regime changes will undermine Russia’s role as kingmaker, and open the door to ongoing Turkish influence-building. This is particularly the case in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, where Turkey seems intent on usurping Russia as a strategic partner with investment in gas corridors.

We forecast resurgent US pressure on Turkey and Russia in 2021, with the Biden administration seeking to reassert the US-led rules-based order. Tougher sanctions on Turkey over its purchase of S-400 and on Russia over its cyber activity abroad are likely.

Image: Burak Kara/Getty Images

Image: Kenzo Tribouillard/Getty Images

Forecasts

Legislative efforts by the government to stifle free speech are likely to disrupt foreign business operations in Turkey in 2021. The authorities want greater control over corporate data and oversight of social media. Fines and office raids are likely for companies that the authorities deem to be flouting regulations.

NO EASY BUSINESS IN TURKEY

Foreigners in Central Asia are likely to be subject to hostile intelligence gathering in 2021. This change will be most apparent in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. This is particularly for those working in sensitive sectors, such as security, telecommunications and technology. The authorities in Kyrgyzstan for example have new legal powers allowing them to investigate individuals on the basis of their social media use.

FOREIGNERS FACING SCRUTINY

We forecast that President Erdogan will launch another military incursion into northern Syria in early 2021. Such moves serve a double purpose: appeasing nationalist backers at home and ensuring the president is involved in negotiations with the Syrian government to resolve the ongoing civil conflict. We doubt that the financial costs around such an operation will prompt a domestic backlash.

TURKISH ADVENTURISM

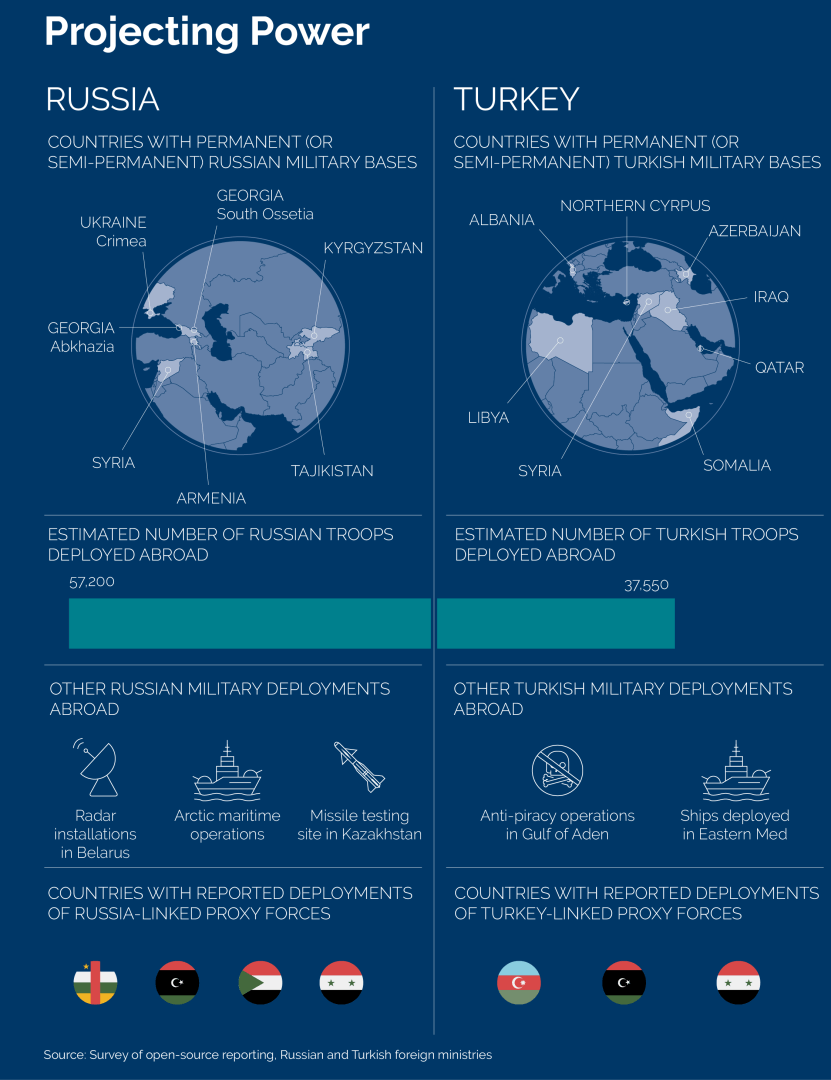

SEMI-PERMANENT) RUSSIAN MILITARY BASES

SEMI-PERMANENT) TURKISH MILITARY BASES

DEPLOYED ABROAD

DEPLOYED ABROAD

Source: Survey of open-source reporting, Russian and Turkish foreign ministries

Forecasts

Outliers

Government collapse in Ukraine

Monitoring Points

BOSPHORUS BLOCKADE

Turkey’s control over the Bosphorus lends it much-needed leverage over any country seeking access to the Black Sea. Increased or onerous customs checks on passing shipping would suggest Turkey is seeking to restate its importance in the region. Similarly, continued easy access for all shipping and naval traffic into the sea would indicate that Turkey is willing to cooperate with Russia.

KAZAKHSTAN ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT

Labour rights in Kazakhstan are proving a contentious issue. Better wages for foreign workers have already led to small bouts of protests at oil fields in the west of the country. Efforts by the government to draw in more Chinese workers to service large infrastructure projects risk labour rights dovetailing with growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country, potentially prompting a period of unrest in 2021.

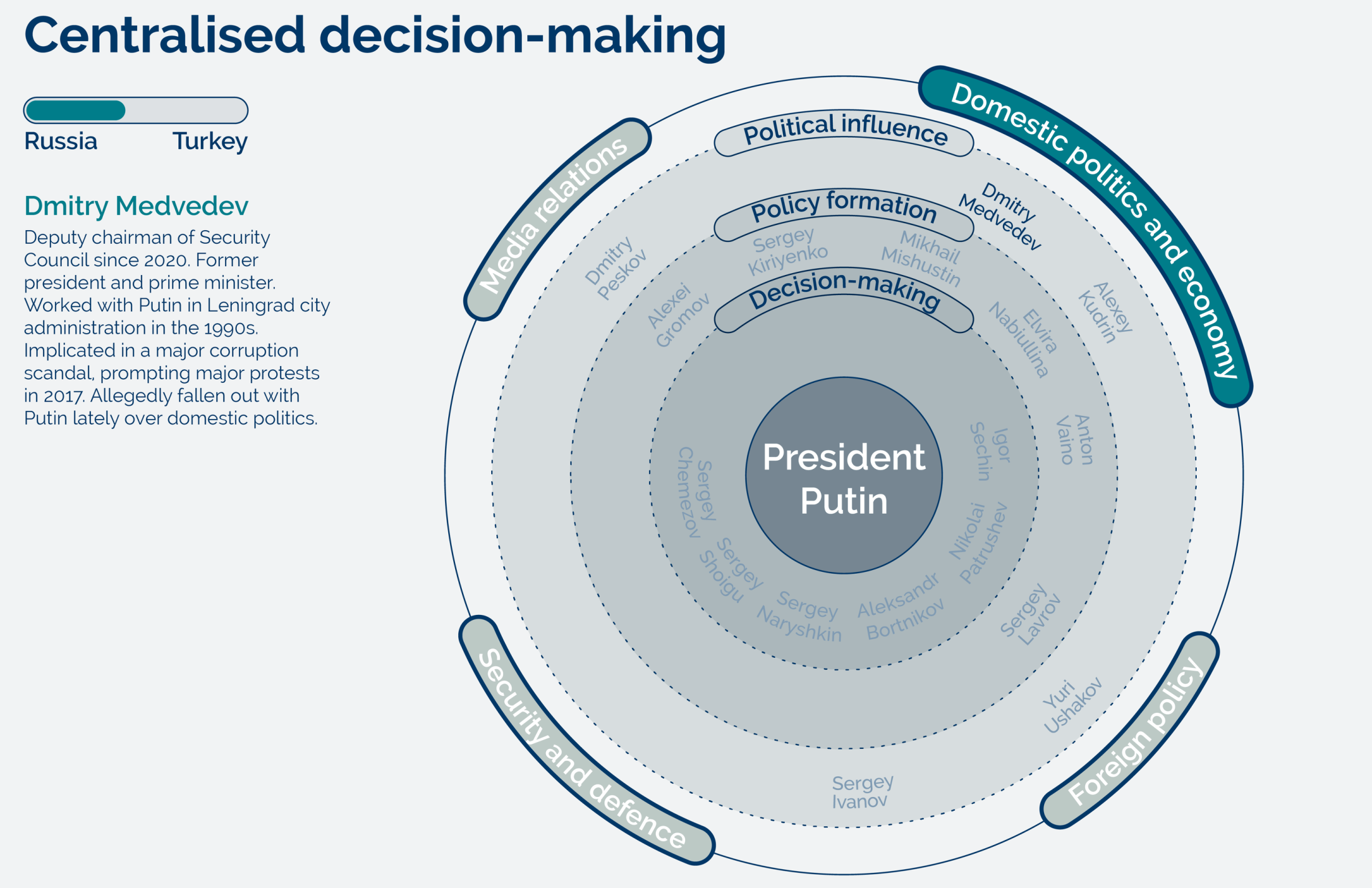

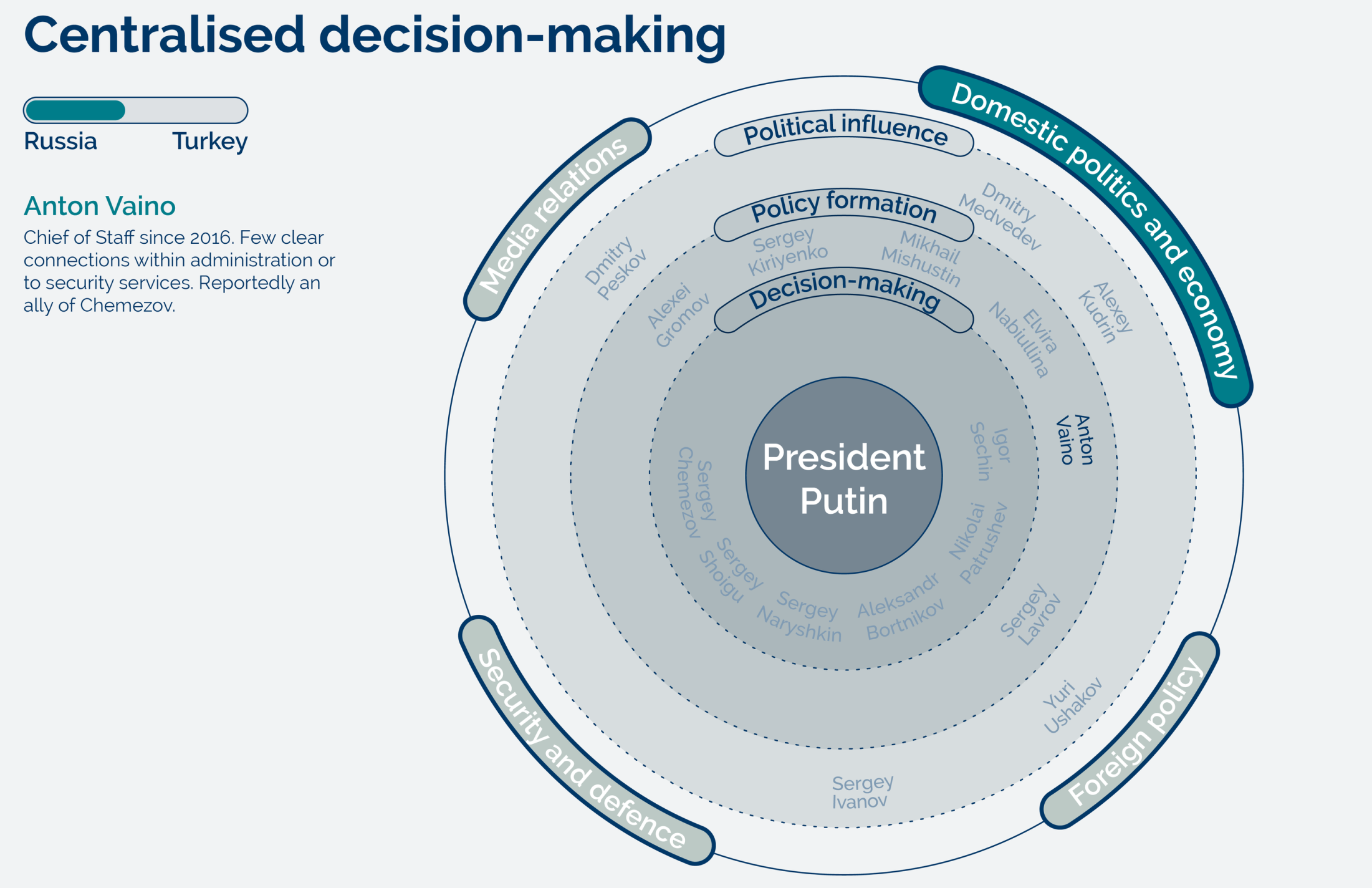

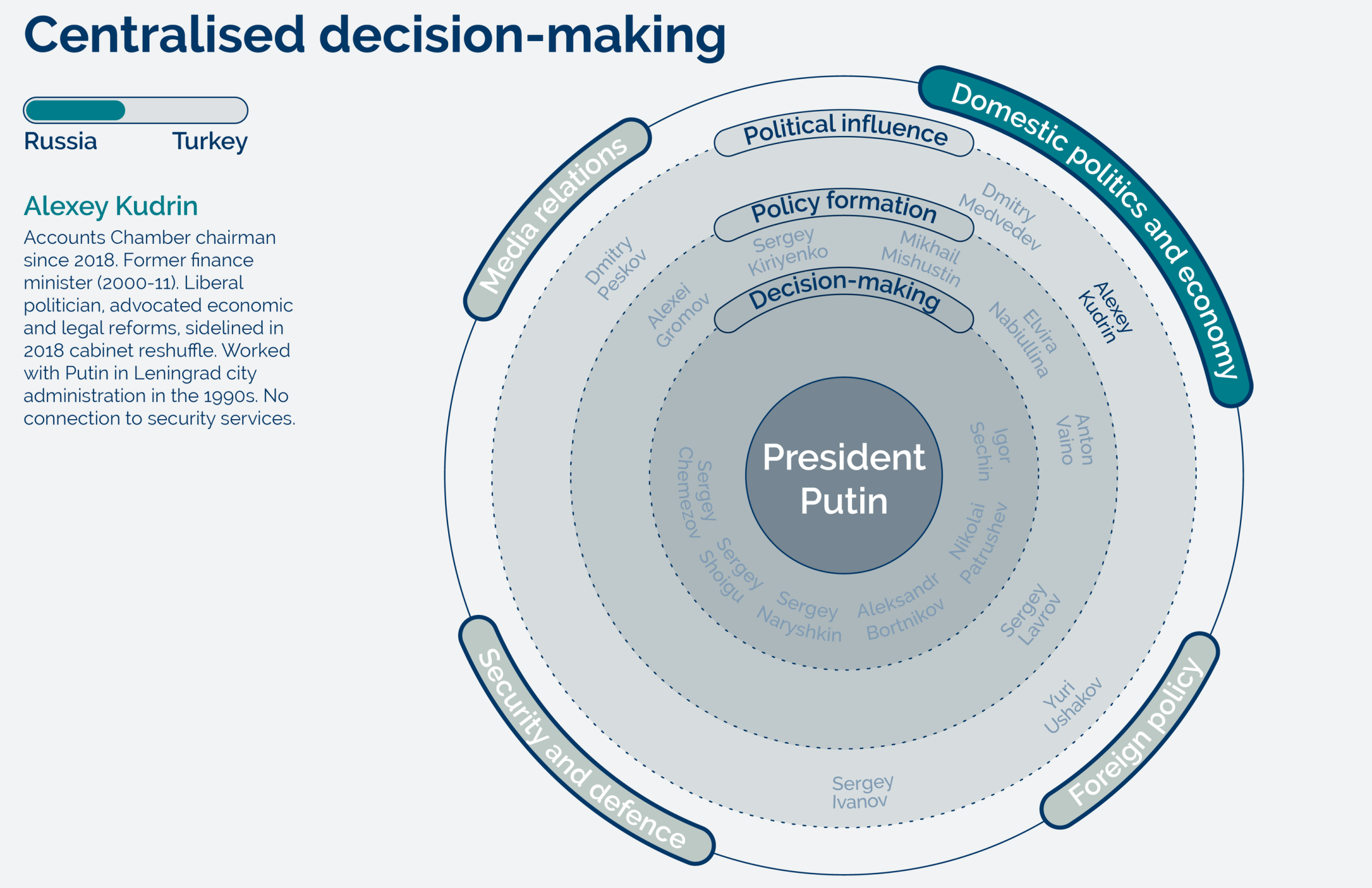

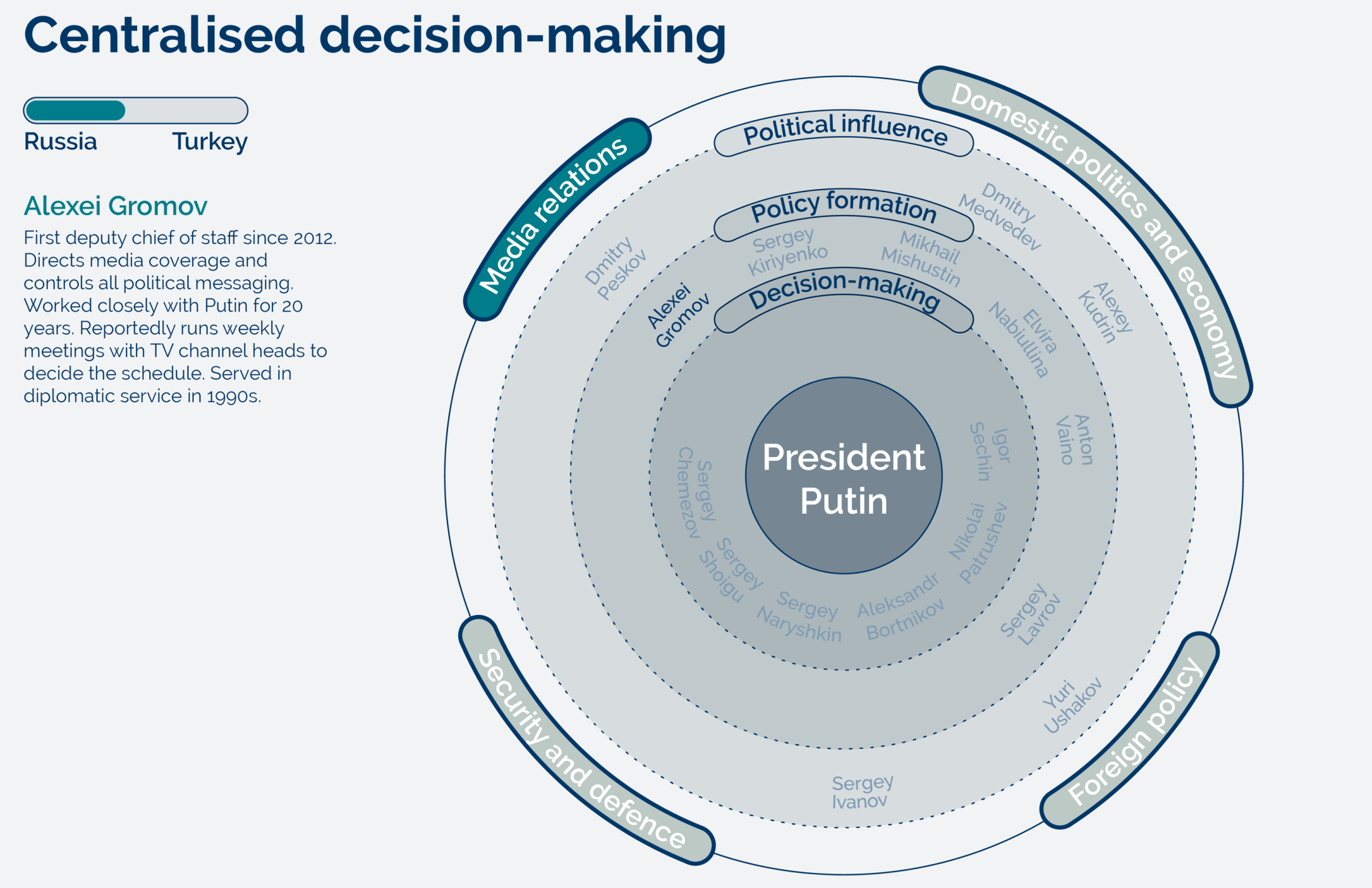

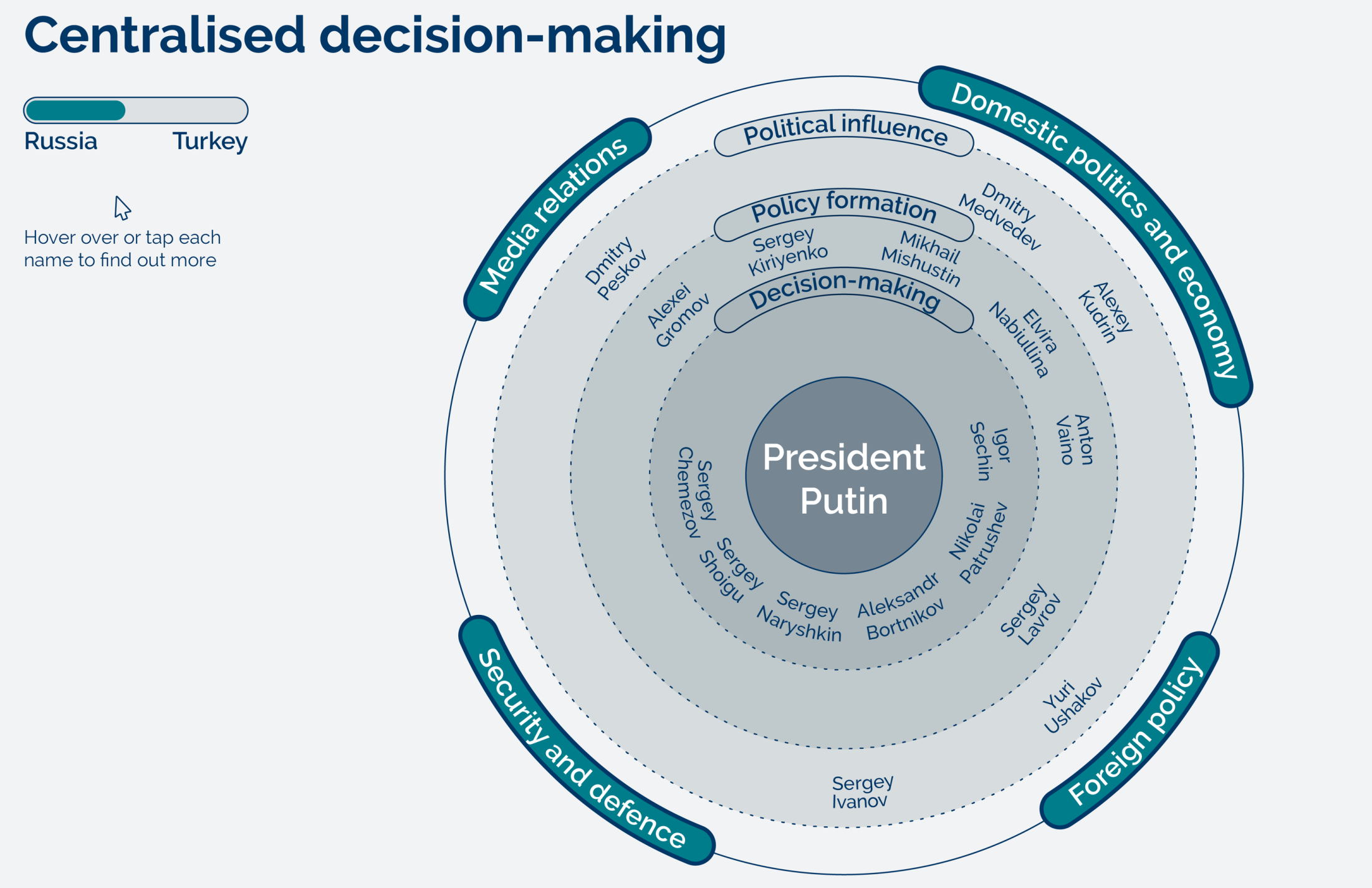

RESTIVE REGIONS FOR THE KREMLIN

The Kremlin appears to be losing its grip on the regions in Russia. Several governors have accrued considerable support with their local populations, who increasingly see Kremlin interference as unwelcome, most recently in Khabarovsk. Unruly governors do not pose a threat to wider stability in the country. But declining political legitimacy would probably distract the Kremlin from its broader agenda in Eurasia.

Images: Chesnot; Milos Bicanski; Lintao Zhang; Burak Kara; Yuri Kadobnov/Getty Images

Overall trend: Consistent

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

President Erdogan and President Putin start the year with a remarkably positive relationship. This is despite them backing opposing sides in now three wars: Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria. This is proof of their ability to compartmentalise foreign policy issues. And Erdogan and Putin are very unlikely to seek a military conflict in 2021. But the Black Sea and northern Syria are areas where competition between Russia and Turkey risks spilling over into diplomatic hostility this year.

Turkey and Russia will probably strive for greater sway in the Black Sea in 2021, pushing up operational risks for maritime traffic. The Kremlin has rejected all agreements on mutual use of the sea. This stance will jar with Turkish efforts to reassert its naval position after it found gas fields there in 2020. But the military balance has shifted in Russia’s favour. And as in the Sea of Azov in recent years, Russian vessels will probably disrupt shipping to establish Russia as the dominant force. This would potentially include inspections and short-notice naval drills rather than any aggressive activity towards commercial vessels.

Turkey would very likely deploy its navy to the Black Sea to check such behaviour, including naval escorts for its shipping. The sea is large enough to accommodate deployments from both, as well as NATO, and so this would not necessarily push up the likelihood of a military escalation. Unlike in the eastern Mediterranean, there is no urgency on either side to confirm its status as the dominant power. But we forecast that the sea will be a source of fluctuating tensions between Russia and Turkey next year, and a bellwether for their ability to maintain a pragmatic relationship.

The eastern Mediterranean will draw speculation as a conflict risk in 2021, but we think misleadingly. NATO pressure on Turkey and Greece to ease military tensions is working. Both cancelled naval drills in late 2020 to allow for talks. We forecast that Turkey and Greece will keep tensions high with gas exploration missions and naval deployments. But this will be mostly artificial. Turkey seems intent on muscling into regional energy planning, while Greece appears focused on forcing EU sanctions on its neighbour. As such, neither is likely to see a military confrontation as within their interests.

We forecast resurgent US pressure on Turkey and Russia in 2021, with the Biden administration seeking to reassert the US-led rules-based order. Tougher sanctions on Turkey over its purchase of S-400 and on Russia over its cyber activity abroad are likely. This will complicate the risks that Western businesses face in Eurasia. We forecast product boycotts and blacklisting becoming more frequent as both governments resist Western diplomatic pressure. Erdogan has put this tactic to use against France and the US, pushing up reputational risks.

These geopolitical tensions between Russia and Turkey will play out in addition to several existing potential crises in Eurasia this year. Belarus and Kyrgyzstan enter the year in a state of flux, with very unstable regimes. Persistent protests since President Lukashenka rigged his re-election last year have weakened his position, and he will probably initiate a power transition this year. The opposition will probably see this as an opportunity to restart their protest campaign, risking further unrest amid another crackdown by the

security forces.

We are flagging Ukraine as one to watch for regime instability in 2021. President Zelensky’s failure to implement structural reforms and tackle Covid-19 has undermined his public support and highlighted the weakness of state institutions. He also lacks a plan to end the conflict in Donbas, a campaign promise. A rushed resolution – or one that the public deems to be a concession to Russia – would make widespread unrest likely. This has the potential to coincide with anger over state-level corruption and stagnant economic conditions this year, potentially forcing the president to step down.

In Central Asia, the operating environment for businesses looks likely to worsen in 2021 amid sliding rule of law and wider regime instability. Acting President Japarov of Kyrgyzstan, who took office after being sprung from jail, has begun consolidating his power, threatening media freedom in particular. And much of his nationalist political capital is built on resisting foreign ownership in the resources sector. Evidence of abuse of power or state-level corruption scandals would be very likely to prompt his rivals to instigate further unrest and demand that he step down.

Bouts of civil unrest are likely to emerge in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan this year. Covid-19 has strained the social contract that has been in place in those countries since the 1990s: improving living standards and stability with limited freedoms. Food shortages and rising prices are the primary trigger for protests in both. These would be unlikely to threaten regime stability themselves. But a perception among the elite that such insurrection threatens their positions would probably bring them to move against their presidents.

Worsening security in central Asia will challenge Russia and China as the key security and economic partners in the region. Unrest will probably force China to demand greater security assurances to its investment, or insist on providing its own as is already the case in southern Tajikistan. Opposition figures taking power in regime changes will undermine Russia’s role as kingmaker, and open the door to ongoing Turkish influence-building. This is particularly the case in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, where Turkey seems intent on usurping Russia as a strategic partner with investment in gas corridors.

Image: Burak Kara/Getty Images

We forecast resurgent US pressure on Turkey and Russia in 2021, with the Biden administration seeking to reassert the US-led rules-based order. Tougher sanctions on Turkey over its purchase of S-400 and on Russia over its cyber activity abroad are likely.

Image: Kenzo Tribouillard/Getty Images

Forecasts

We forecast that President Erdogan will launch another military incursion into northern Syria in early 2021. Such moves serve a double purpose: appeasing nationalist backers at home and ensuring the president is involved in negotiations with the Syrian government to resolve the ongoing civil conflict. We doubt that the financial costs around such an operation will prompt a domestic backlash.

TURKISH ADVENTURISM

Legislative efforts by the government to stifle free speech are likely to disrupt foreign business operations in Turkey in 2021. The authorities want greater control over corporate data and oversight of social media. Fines and office raids are likely for companies that the authorities deem to be flouting regulations.

NO EASY BUSINESS IN TURKEY

Foreigners in Central Asia are likely to be subject to hostile intelligence gathering in 2021. This change will be most apparent in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. This is particularly for those working in sensitive sectors, such as security, telecommunications and technology. The authorities in Kyrgyzstan for example have new legal powers allowing them to investigate individuals on the basis of their social media use.

FOREIGNERS FACING SCRUTINY

SEMI-PERMANENT) RUSSIAN MILITARY BASES

SEMI-PERMANENT) TURKISH MILITARY BASES

DEPLOYED ABROAD

DEPLOYED ABROAD

Outliers

Government collapse in Ukraine

Monitoring Points

BOSPHORUS BLOCKADE

KAZAKHSTAN ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT

Turkey’s control over the Bosphorus lends it much-needed leverage over any country seeking access to the Black Sea. Increased or onerous customs checks on passing shipping would suggest Turkey is seeking to restate its importance in the region. Similarly, continued easy access for all shipping and naval traffic into the sea would indicate that Turkey is willing to cooperate with Russia.

RESTIVE REGIONS FOR THE KREMLIN

The Kremlin appears to be losing its grip on the regions in Russia. Several governors have accrued considerable support with their local populations, who increasingly see Kremlin interference as unwelcome, most recently in Khabarovsk. Unruly governors do not pose a threat to wider stability in the country. But declining political legitimacy would probably distract the Kremlin from its broader agenda in Eurasia.

Labour rights in Kazakhstan are proving a contentious issue. Better wages for foreign workers have already led to small bouts of protests at oil fields in the west of the country. Efforts by the government to draw in more Chinese workers to service large infrastructure projects risk labour rights dovetailing with growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country, potentially prompting a period of unrest in 2021.

Images: Chesnot; Milos Bicanski; Lintao Zhang; Burak Kara; Yuri Kadobnov/Getty Images