CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Consistent

Image: Francisco Seco/Getty Images

A burst of social unrest and upheaval is likely in Europe in the second quarter of 2021. But first the region must contend with a period of relative stasis, as most countries remain under restrictions or lockdowns due to Covid-19. Hostile states such as China and Russia are likely to use this time to position themselves to profit from instability when lockdowns are lifted. This would bring a range of operational and strategic risks, from activism and terrorism to governance failures and even the nationalisation of key industries. But at the same time, the EU is likely to find a new sense of purpose amid the crisis.

for renewal

The European Union appears to see the pandemic as a watershed moment for it to regain a sense of mission, particularly following the lessons of Brexit. We forecast greater harmony between member states in 2021, as they work to defend the bloc against a range of pressures. Economic downturn is likely to preoccupy them the most. But another focus will probably be protecting itself against hostile states, particularly China and to a lesser extent Russia.

The EU and its members states seems likely to make progress on both fronts this year, slowly building its longer-term resilience. We also forecast that EU member states will make gradual steps forward on forming a common security strategy, something the bloc has long lacked. This would

also set the region on a longer-term track of asserting greater independence from the US on foreign and military policy, even with renewed efforts for engagement from the incoming

Biden administration.

The socioeconomic impacts of Covid-19 are feeding into anti-government sentiment in much of Europe. Large protests and bouts of unrest are most likely in Czech Republic, France, Romania, Spain, the UK, and to a lesser extent Italy. These all had large protest movements before the pandemic, and

their healthcare systems and economies have

been among the hardest hit. There are also signs that there will be an accompanying rise in

activism from anti-liberalist extremists across

the political spectrum.

It will probably only be towards April or May that these movements gain significant traction on the streets. This is partly because of restrictions on gatherings and high Covid-19 infection rates are likely to deter many people from taking part; restrictions and anxieties about the virus should ease with vaccine deployment and warmer weather. But it is also around the spring that we forecast much of the extraordinary state financial support for businesses and individuals will have come to an end. Even with a vaccine and economic stabilisation towards the summer, this is unlikely to have filtered through into improvements in livelihoods.

The prospect of social unrest will probably give urgency to EU coordination on responses to managing the costs and economic damage from the pandemic. There are clear signs that the pandemic has created a new willingness among EU states to cooperate. This involves accepting highly-controversial mutualisation of debt. Given this, there is a strong prospect of the region avoiding liquidity and fiscal crises, and so preventing bouts of unrest spiralling into more severe security or political crises.

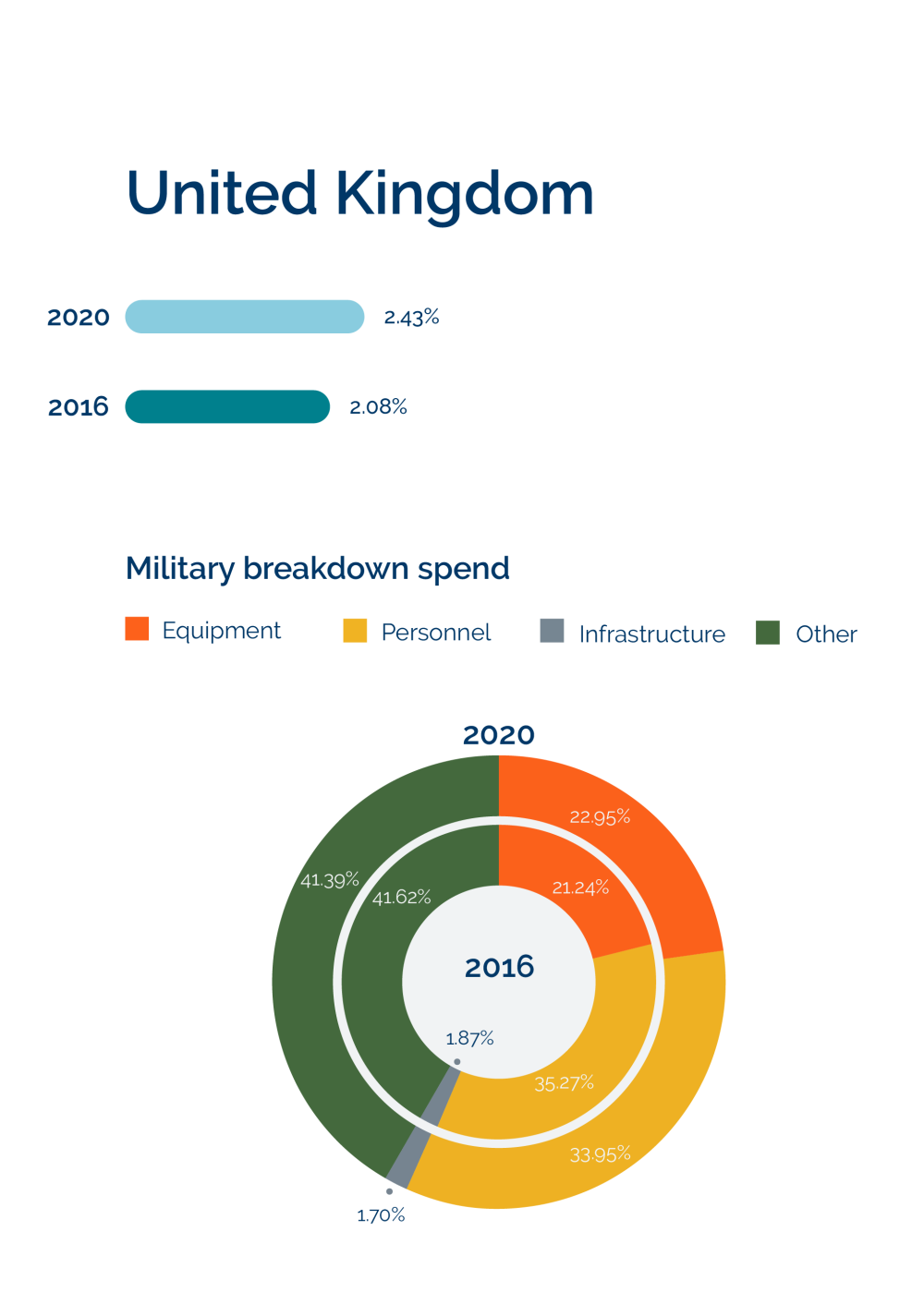

The UK is one exception to this. Sitting outside EU financial cooperation efforts, and with the added impact of Brexit and disrupted trade, the UK will probably fail to stabilise its economy this year. A prolonged period of economic stagnation, high unemployment and rising economic disparities seems likely. And with this, there is a reasonable possibility that the prime minister will face a vote of no confidence over his government’s handling of the pandemic, more likely towards the end of the year. A sharp rise in poverty tied with cuts to police budgets is likely to drive crime levels up.

Greater unity among EU member states will

come at a political cost. Gaining the cooperation

of Poland and Hungary will require the EU to ease its rhetoric on upholding the rule of law. Greater government influence over the judiciary and

media in both countries is likely as a result.

We also forecast that their nativist ideologies will lead the two governments to seek more control

over strategically important sectors, potentially through partial nationalisation. This includes finance and energy.

Uneven application of the law and levelling false allegations are two tactics that the Polish and Hungarian governments seem most likely to use against those that stand in their way of increasing government stakes in industry. And with compromised judiciaries in both countries, legal recourse for those affected will become less reliable. The European Court of Justice is likely to become increasingly drawn into political debate as it remains the ultimate arbiter of legal challenges. But enforcing its rulings will be difficult with a diplomatically cautious European Commission.

The economic and social impact of the pandemic is creating vulnerabilities that states hostile to European liberal democracy, such as China and Russia, can exploit. China in particular seems to be using its economic heft to build influence, such as by providing loans and embedding itself in European economies. Distressed businesses and government finances will give China more opportunities for this in the coming year. Russia seems less able to pursue such a strategy, so instead will probably continue to rely on blunter approaches such as spreading disinformation.

Protecting its member’s economies from such foreign influence is becoming a greater priority more generally in the EU. We anticipate that some European countries will adopt new approaches in defence of economic and democratic liberalism. They are also likely to give broader application to measures limiting investments, loans and ownership stakes in sensitive sectors from entities with ties to states outside the bloc, aimed at limiting the economic and political leverage of China or Russia in the region specifically.

The implications of greater Chinese economic power in Europe go beyond economic and technological intelligence gathering. Propaganda from China during the pandemic has aimed to undermine public confidence in European governance systems, instead positing the Chinese model as a more effective way to ensure public health and economic stability. We forecast a renewed campaign of misinformation and disinformation from both China and Russia early this year, aimed at exacerbating risks around social upheaval and popular discontent over how governments have handled the pandemic.

There are potential longer-term impacts on governance standards stemming from this foreign interference. China in particular seems to be focusing on central and eastern Europe, where democratic governance systems are less developed. It appears to view these as states as vulnerable and that it can over time turn away from a western democratic model. Countries such as Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia are to varying extents already moving towards a more centralised and autocratic model.

China is likely to struggle to move this much further forward this year, however. In the past couple of years it has lost diplomatic ground in central and eastern Europe, as its 17+1 initiative involving 17 European states has faltered due to a lack of engagement. We forecast that China will try to revitalise this economic and development cooperation group, offering more financing. But with greater economic support at an EU level and tougher regulations on non-EU investment, Europe is slowly becoming more resilient to external and internal threats to unravel the union.

The prospect of social unrest will probably give urgency to EU coordination on responses to managing the costs and economic damage from the pandemic. There are clear signs that the pandemic has created a new willingness among EU states to cooperate.

We forecast a renewed campaign of misinformation and disinformation from both China and Russia early this year, aimed at exacerbating risks around social upheaval and popular discontent over how governments have handled the pandemic.

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Image: WPA Pool/Getty Images

Forecasts

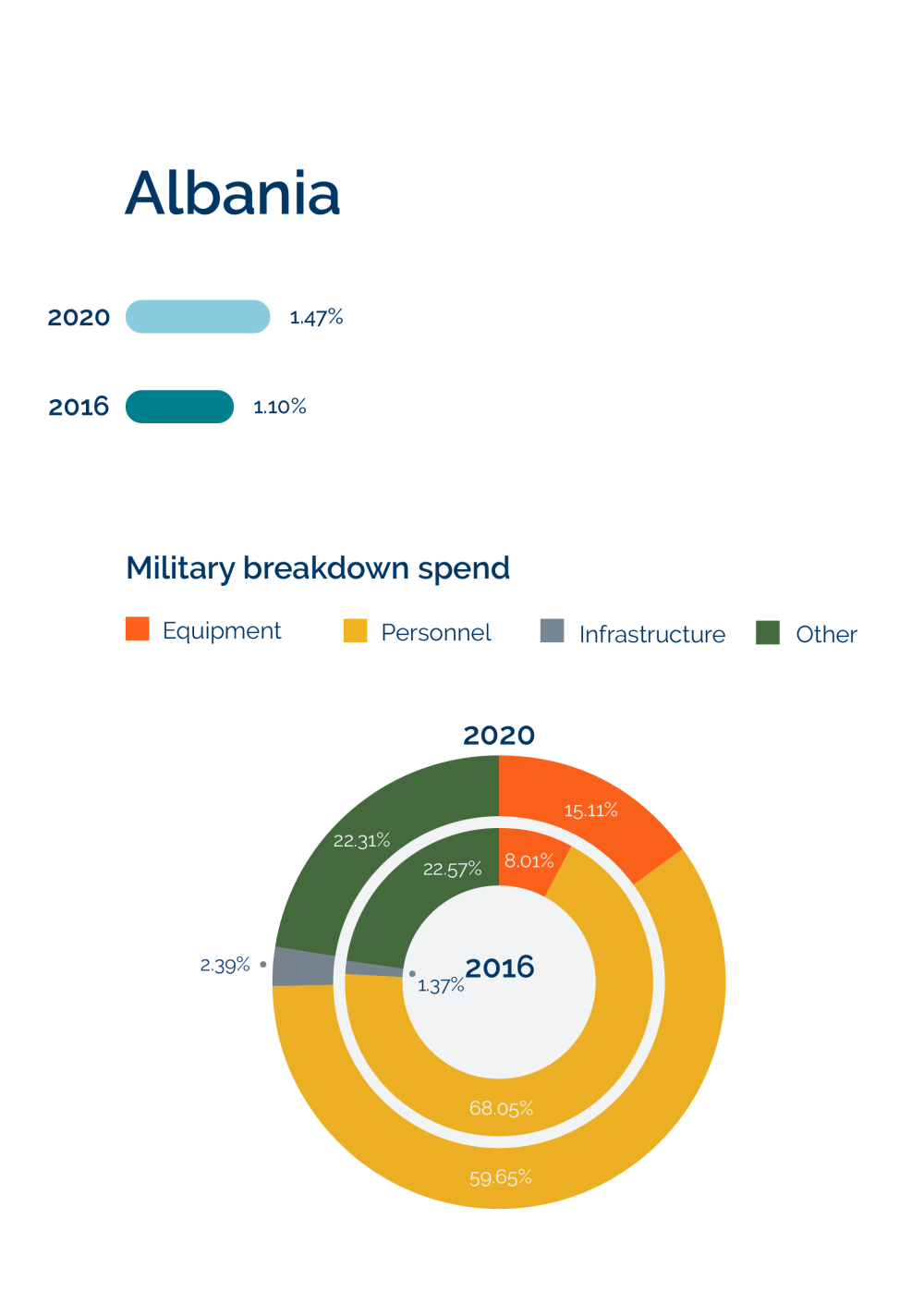

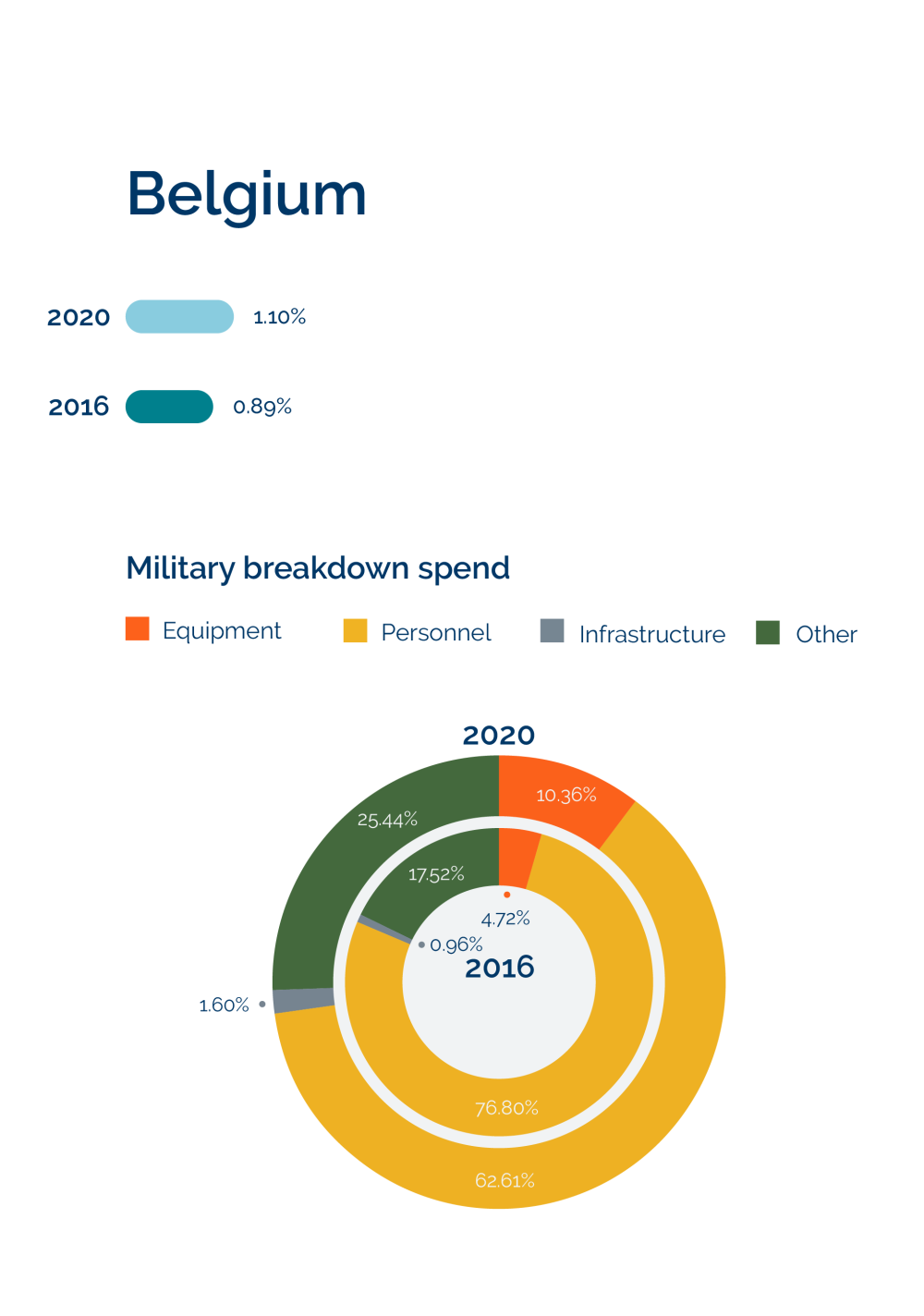

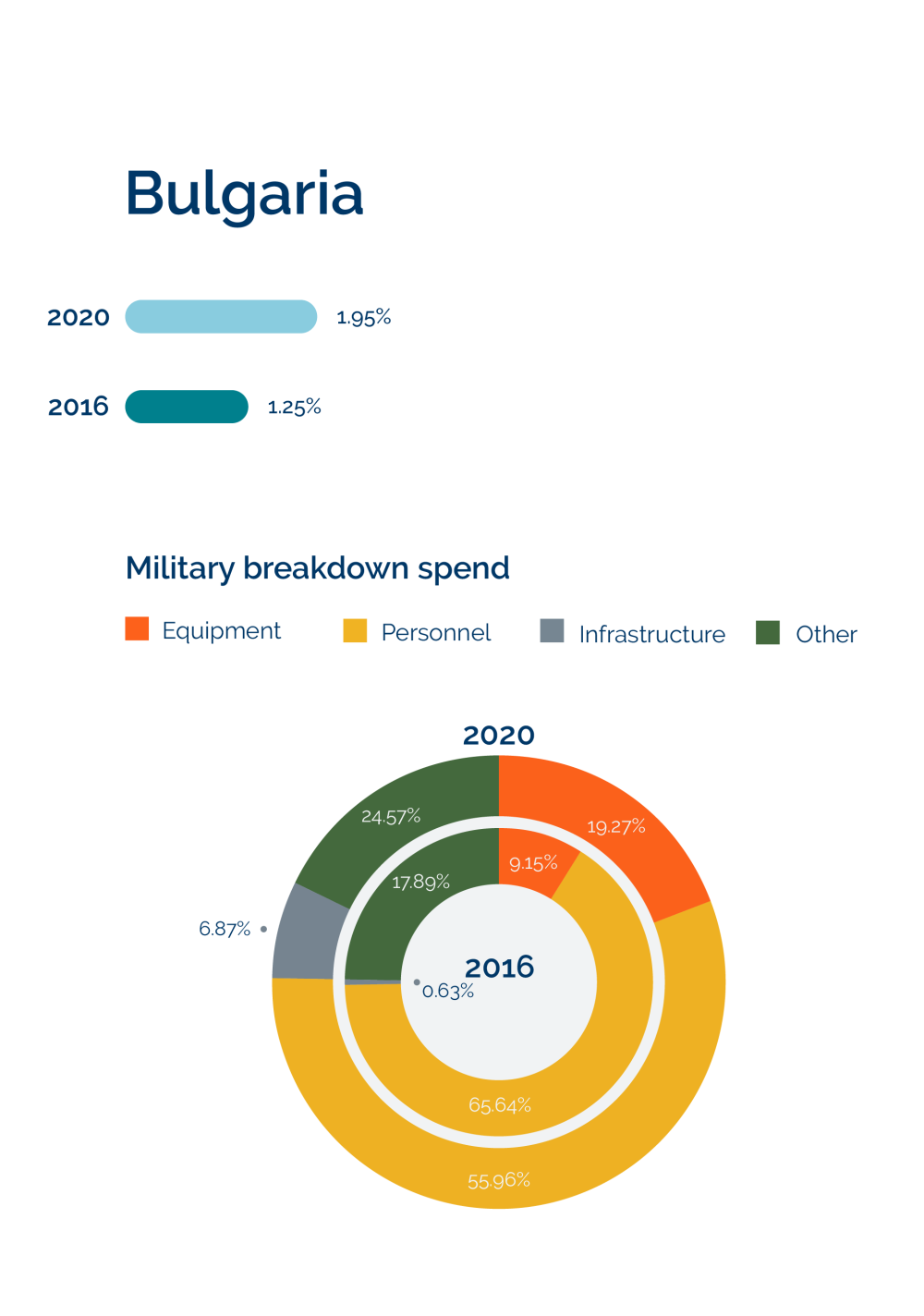

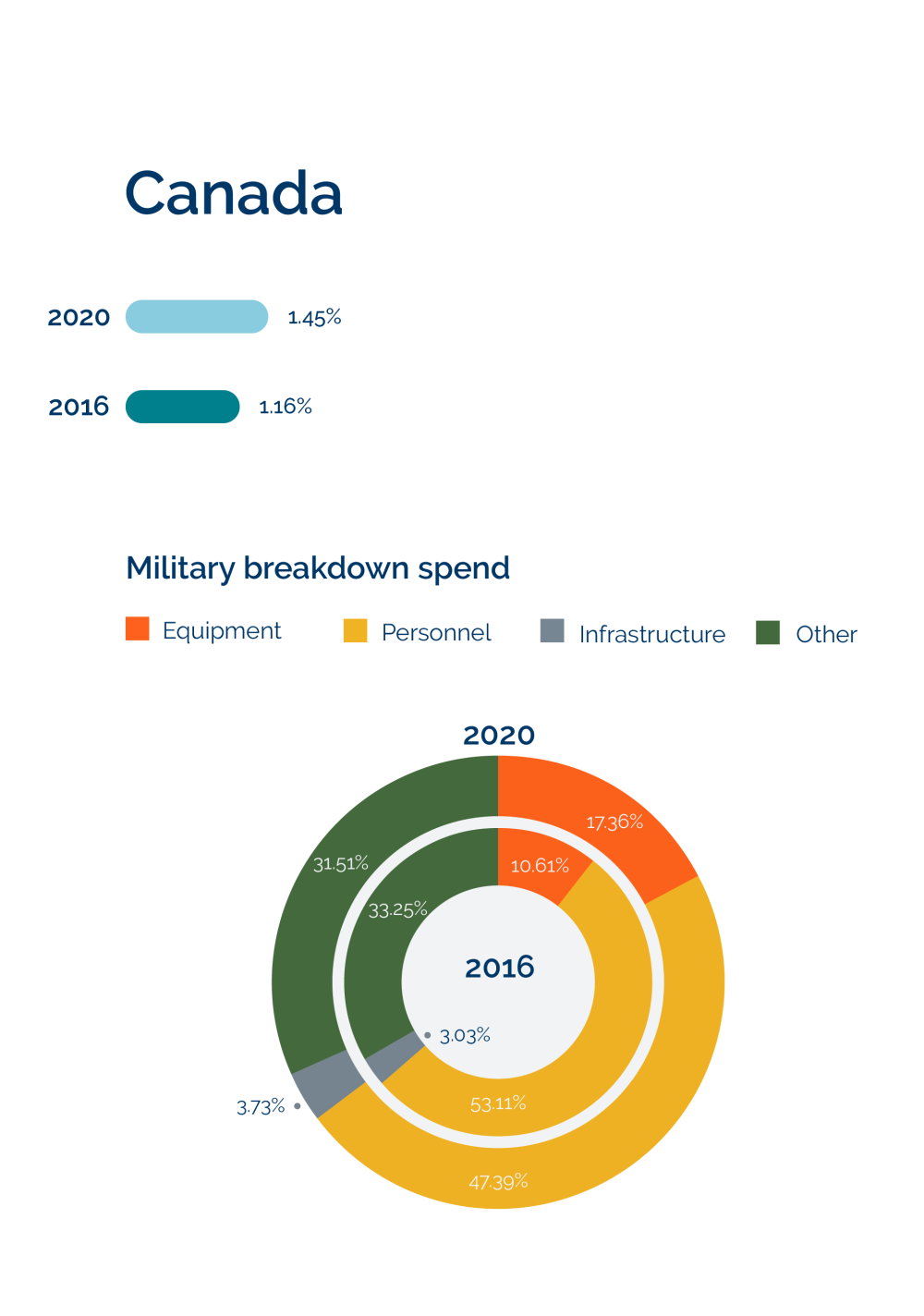

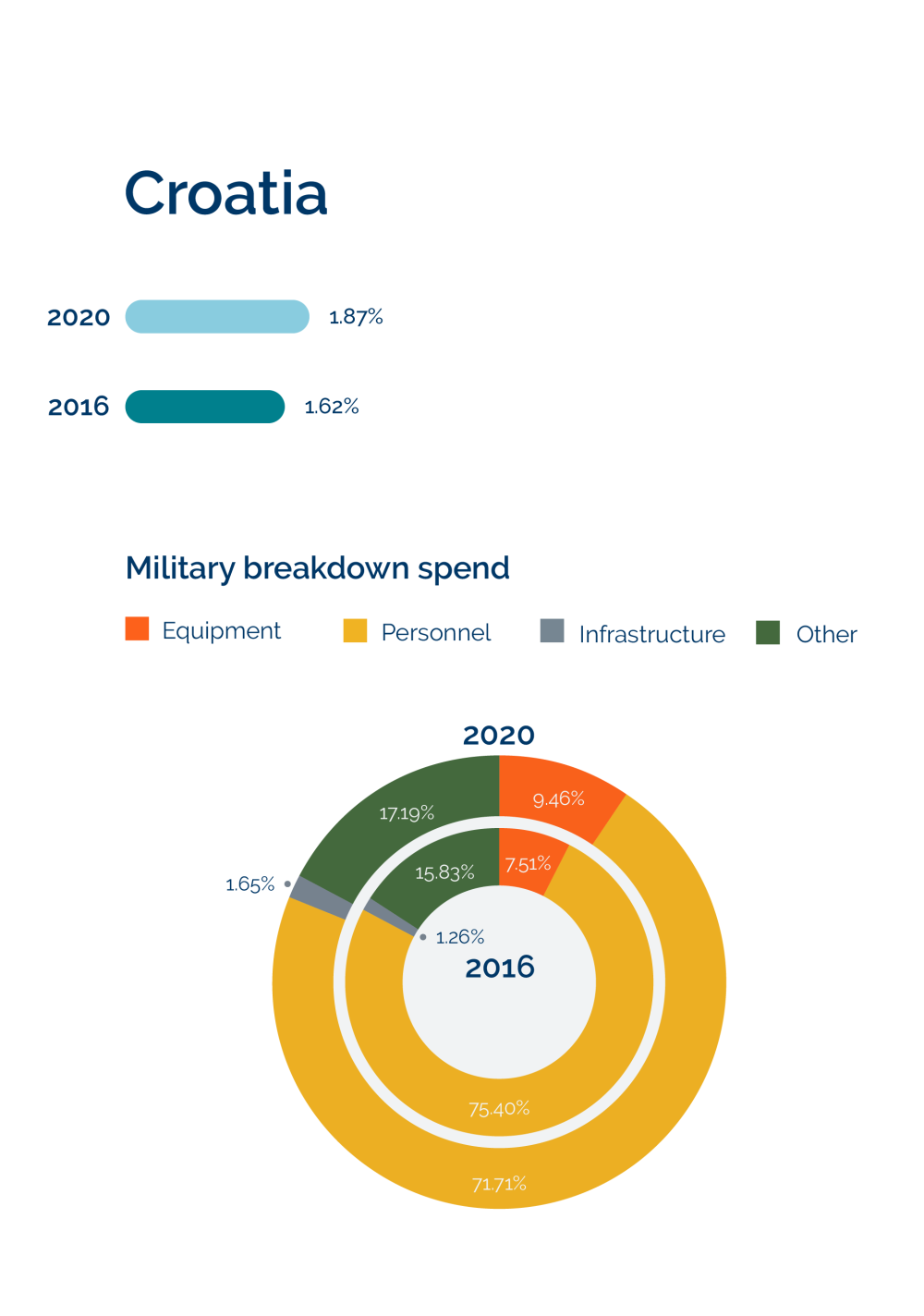

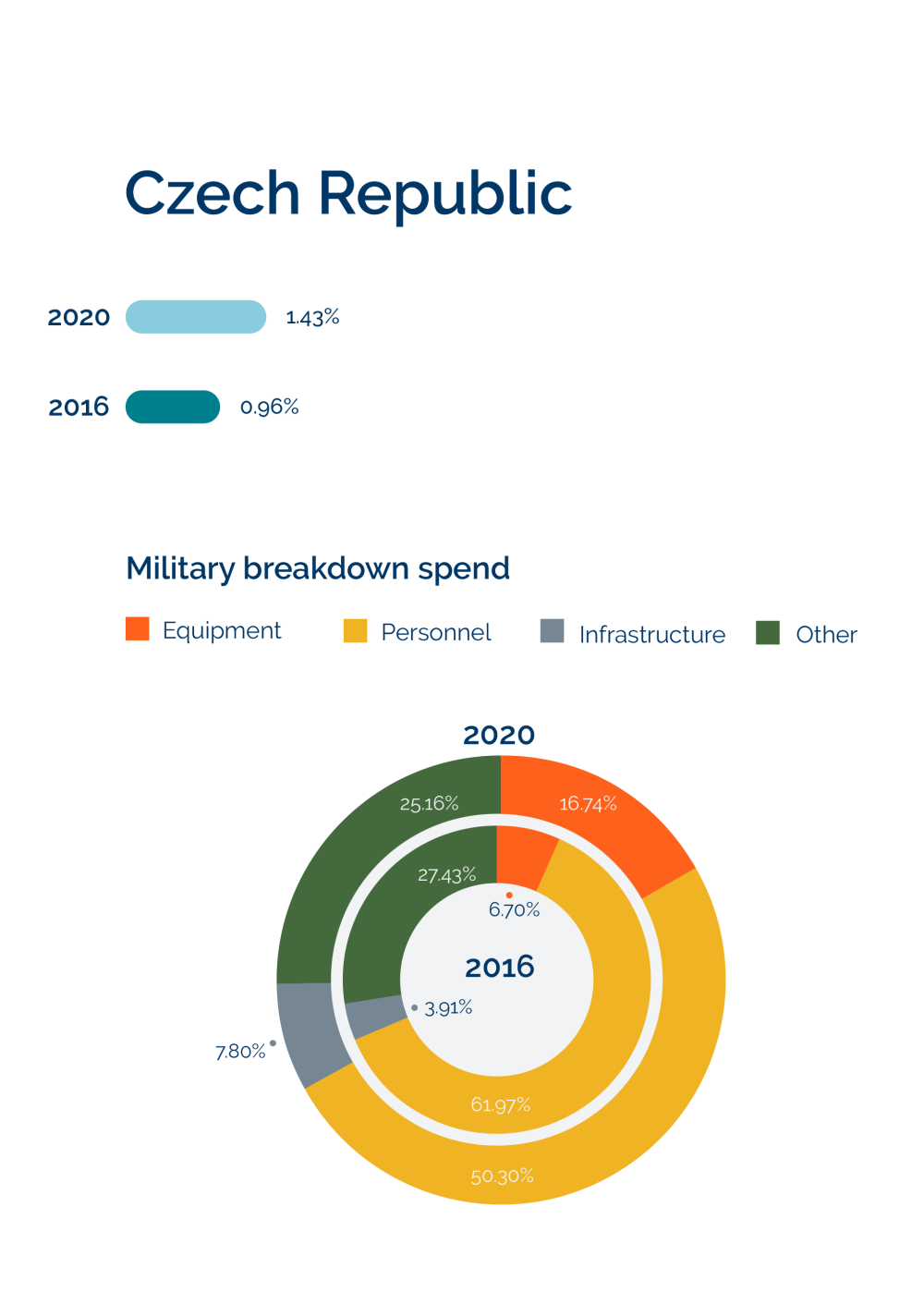

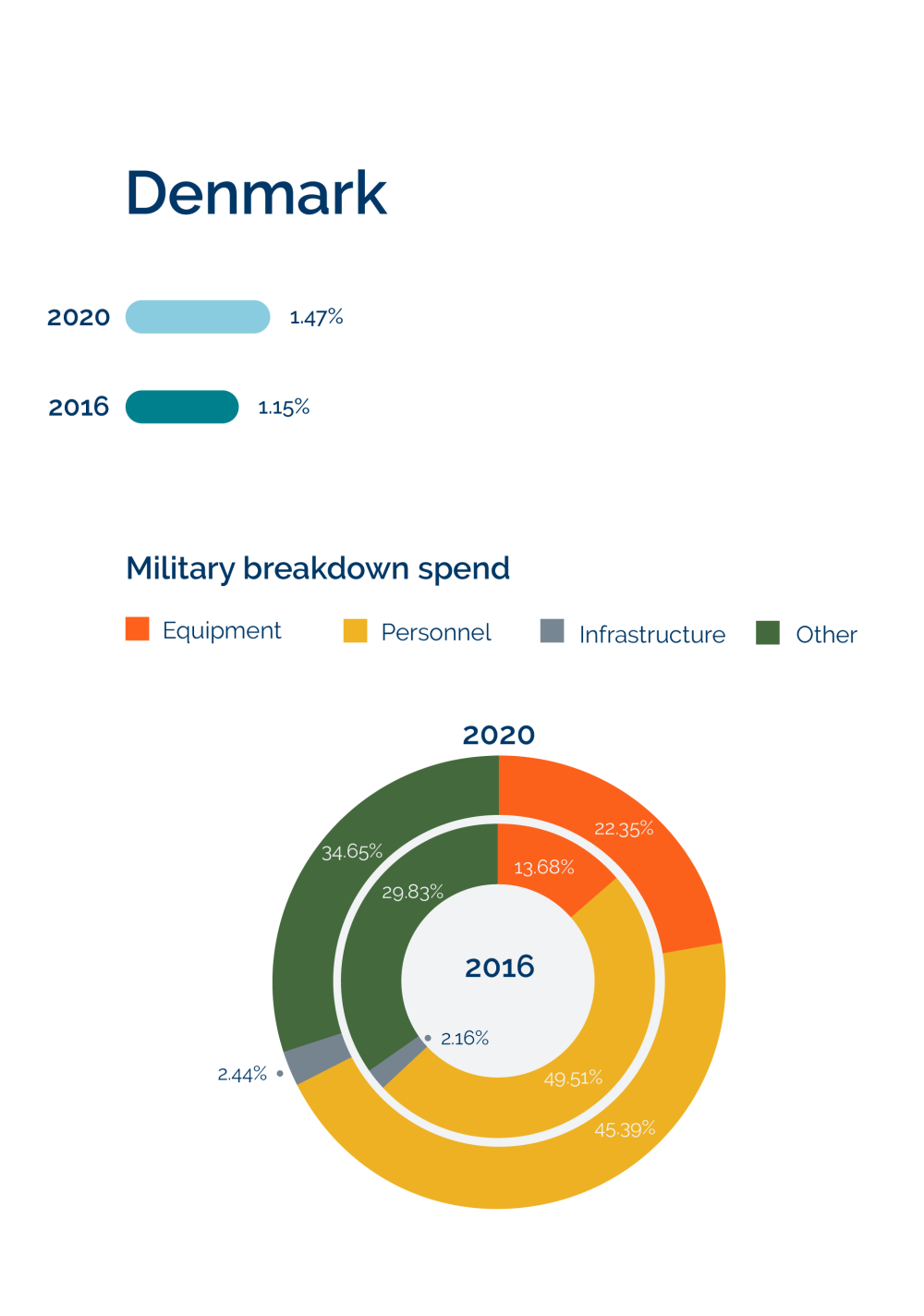

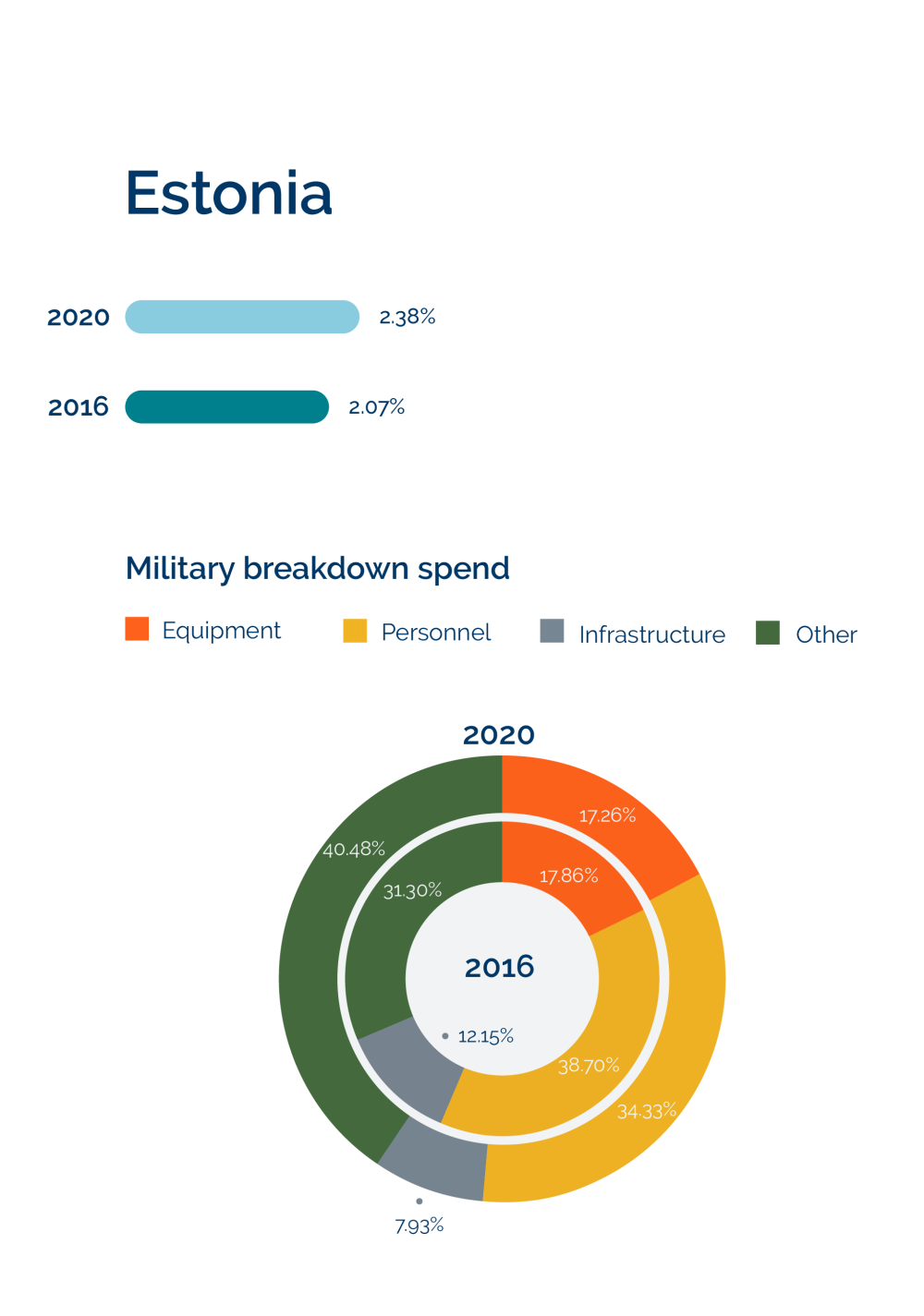

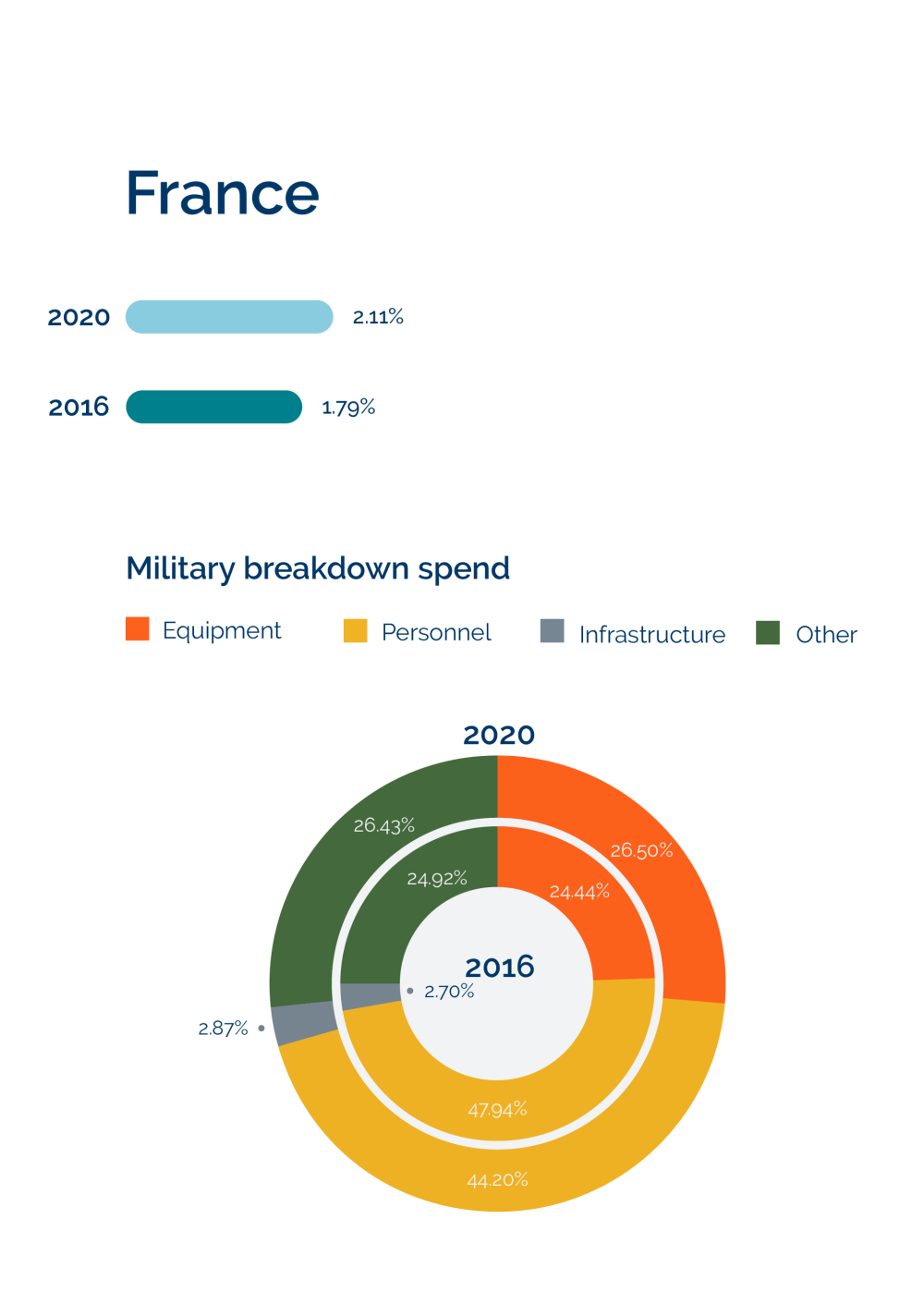

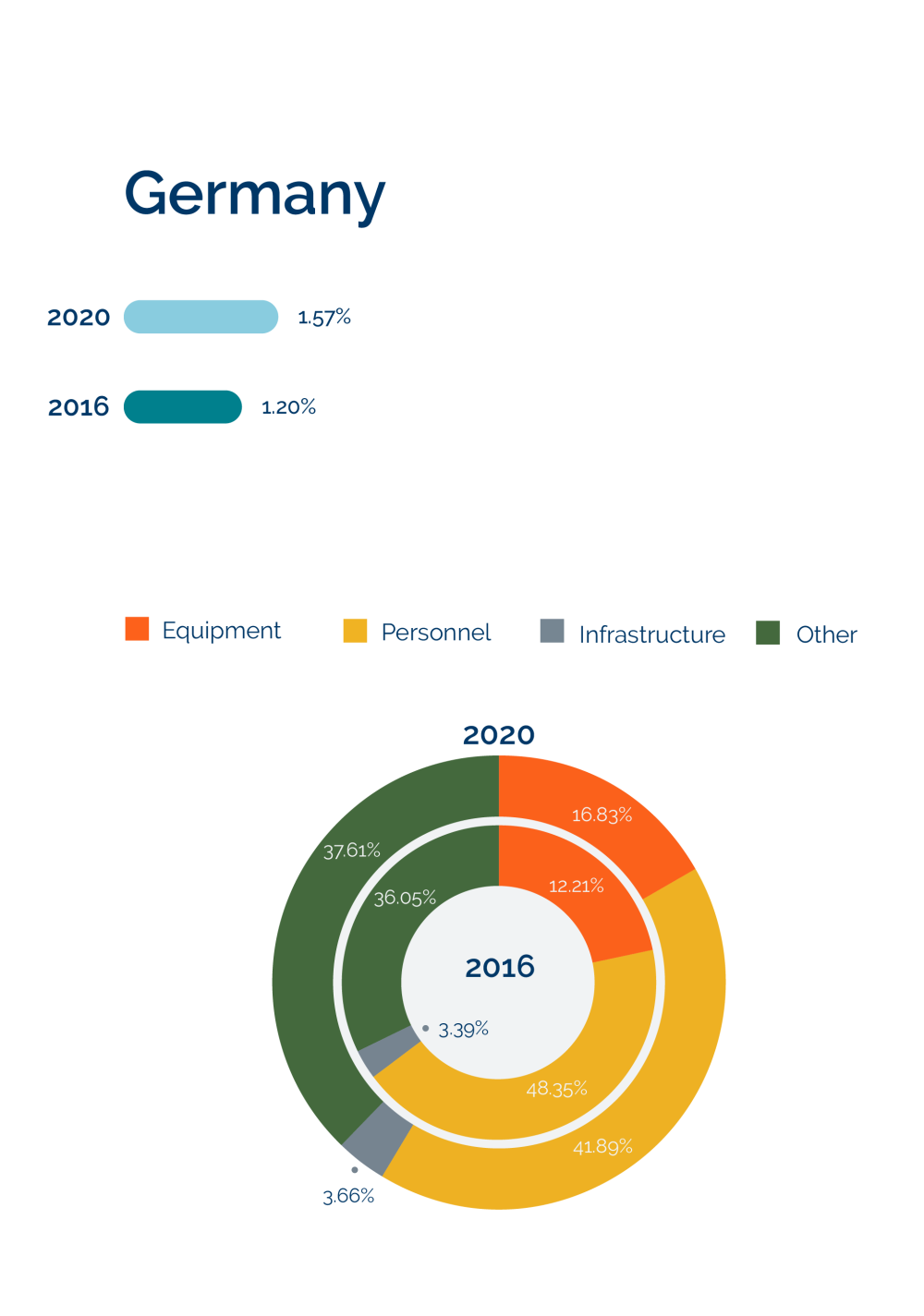

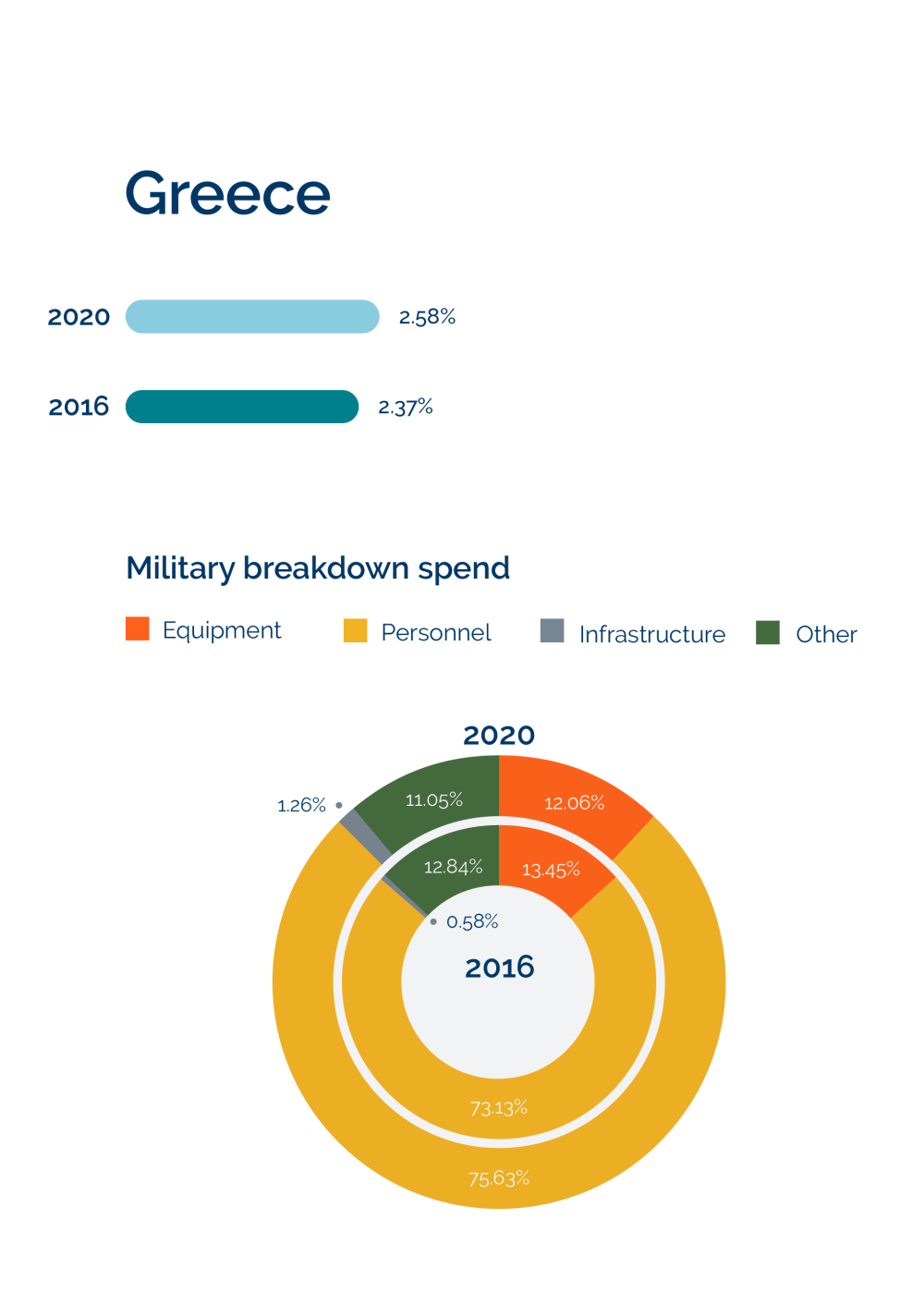

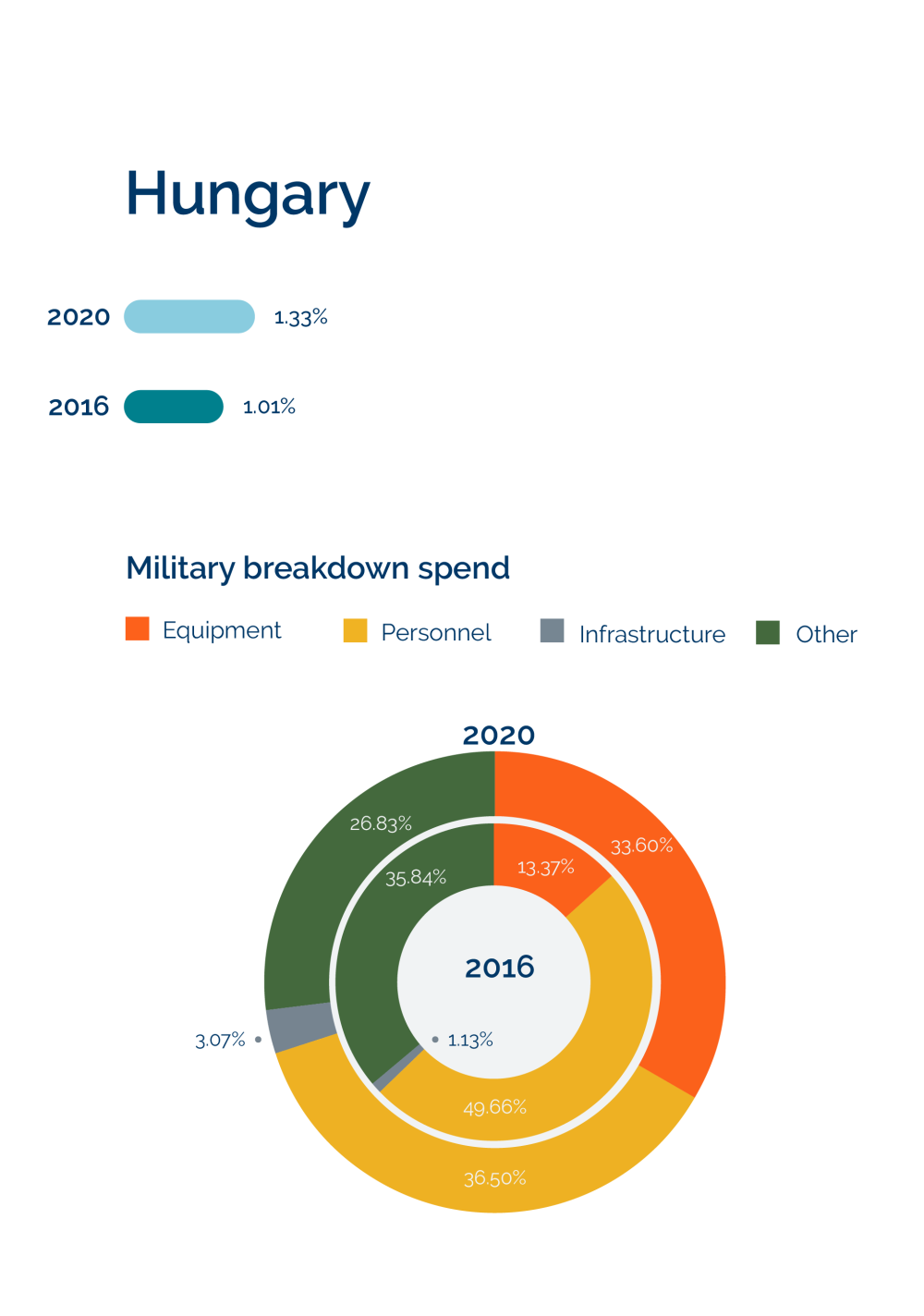

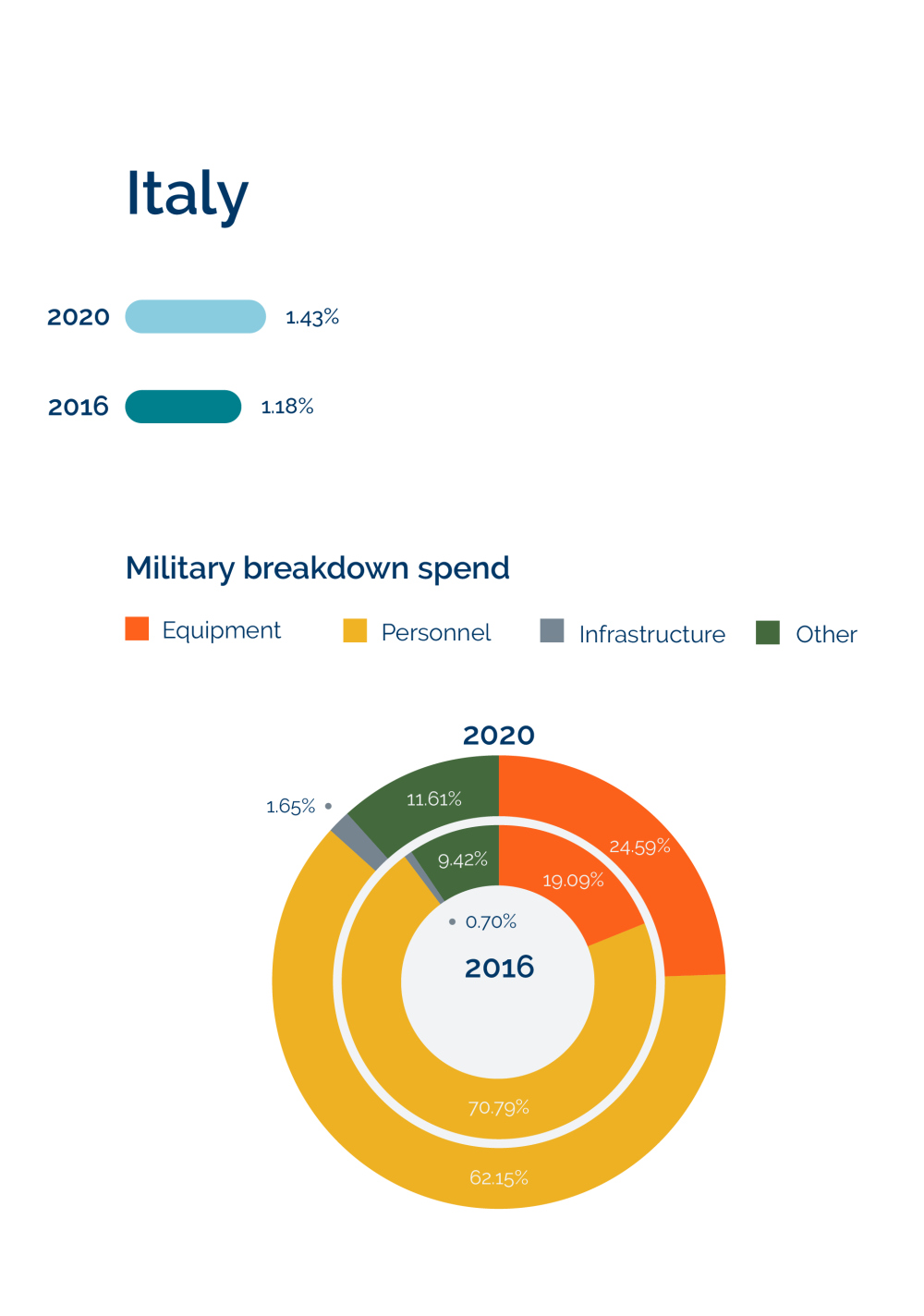

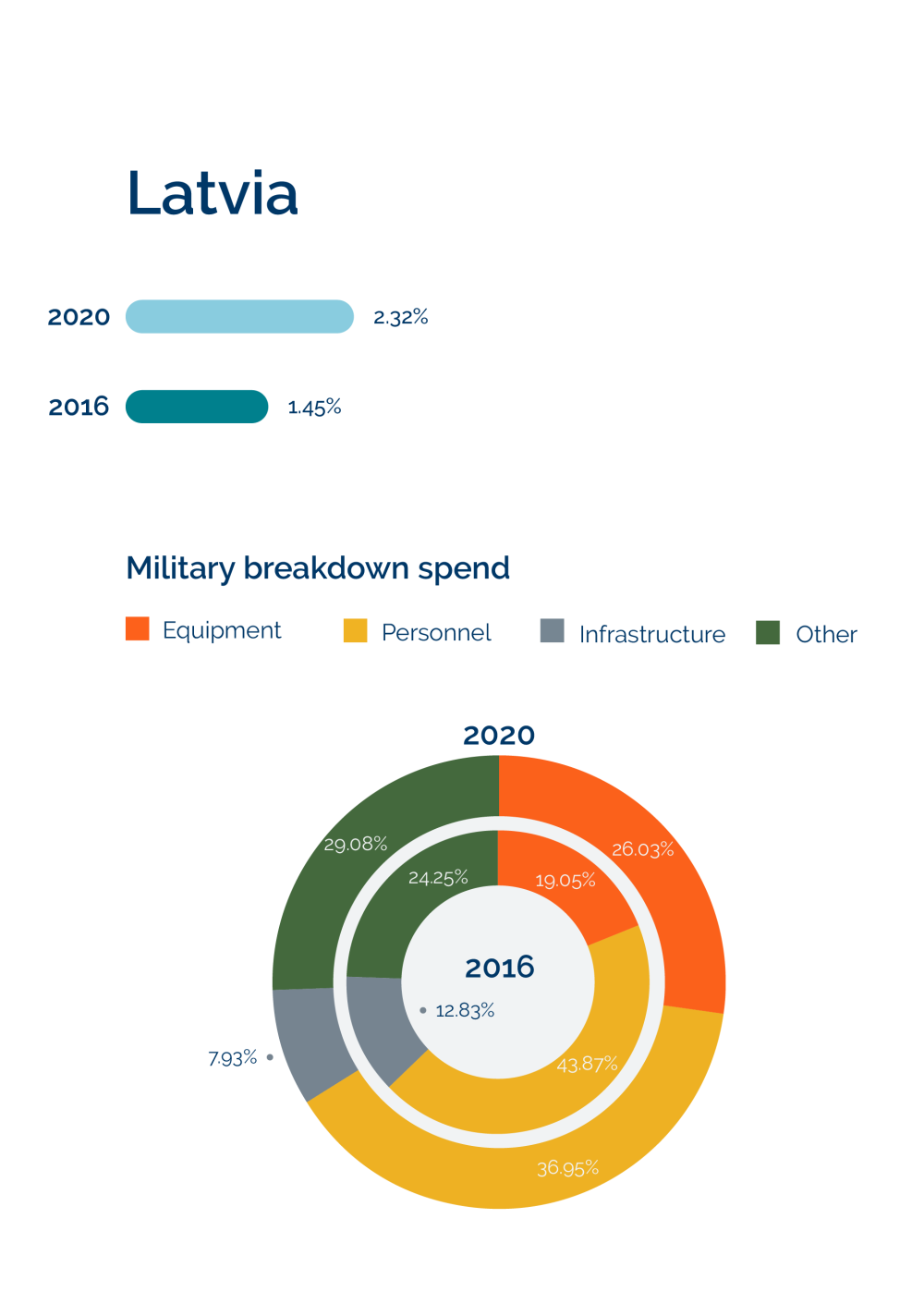

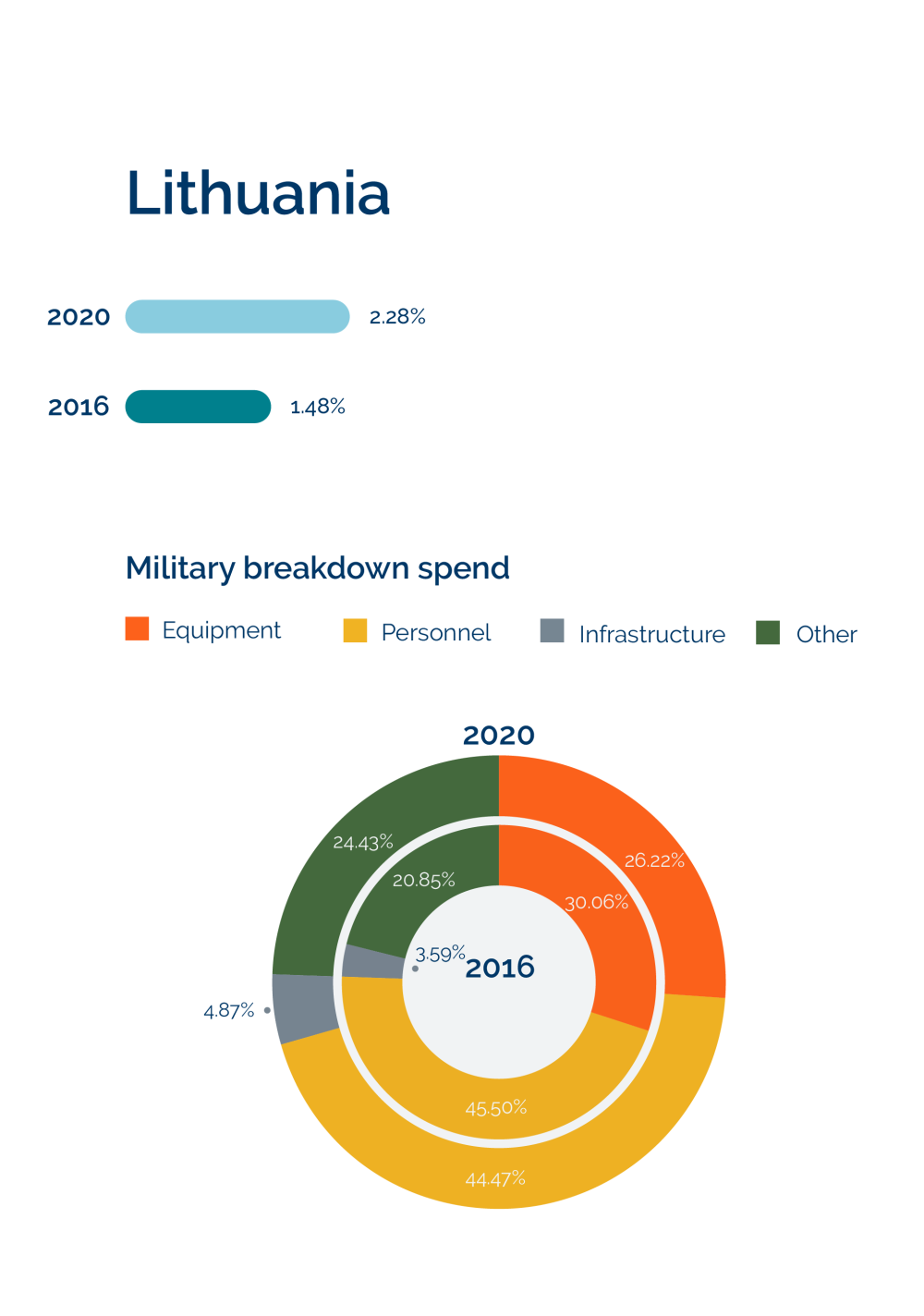

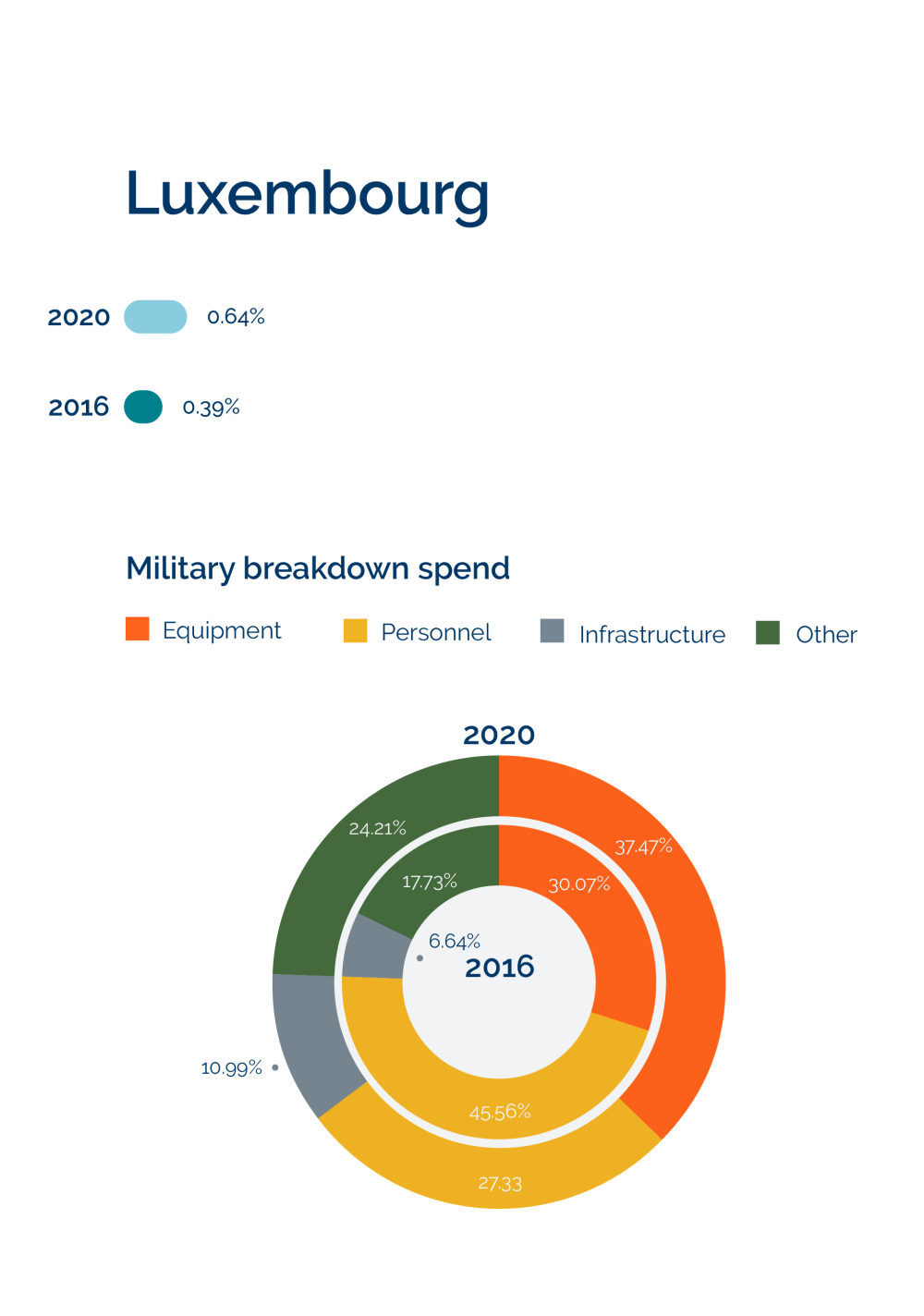

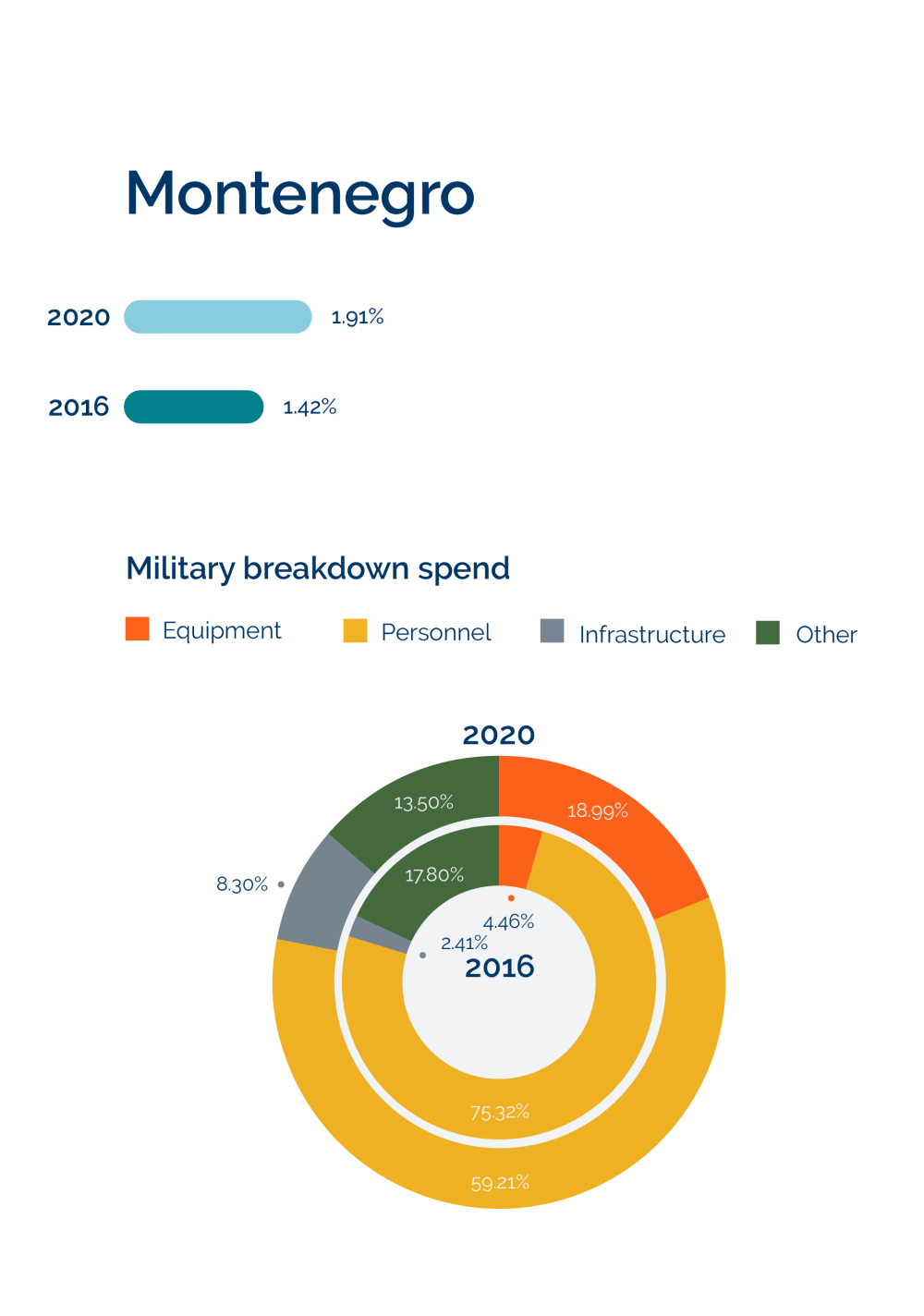

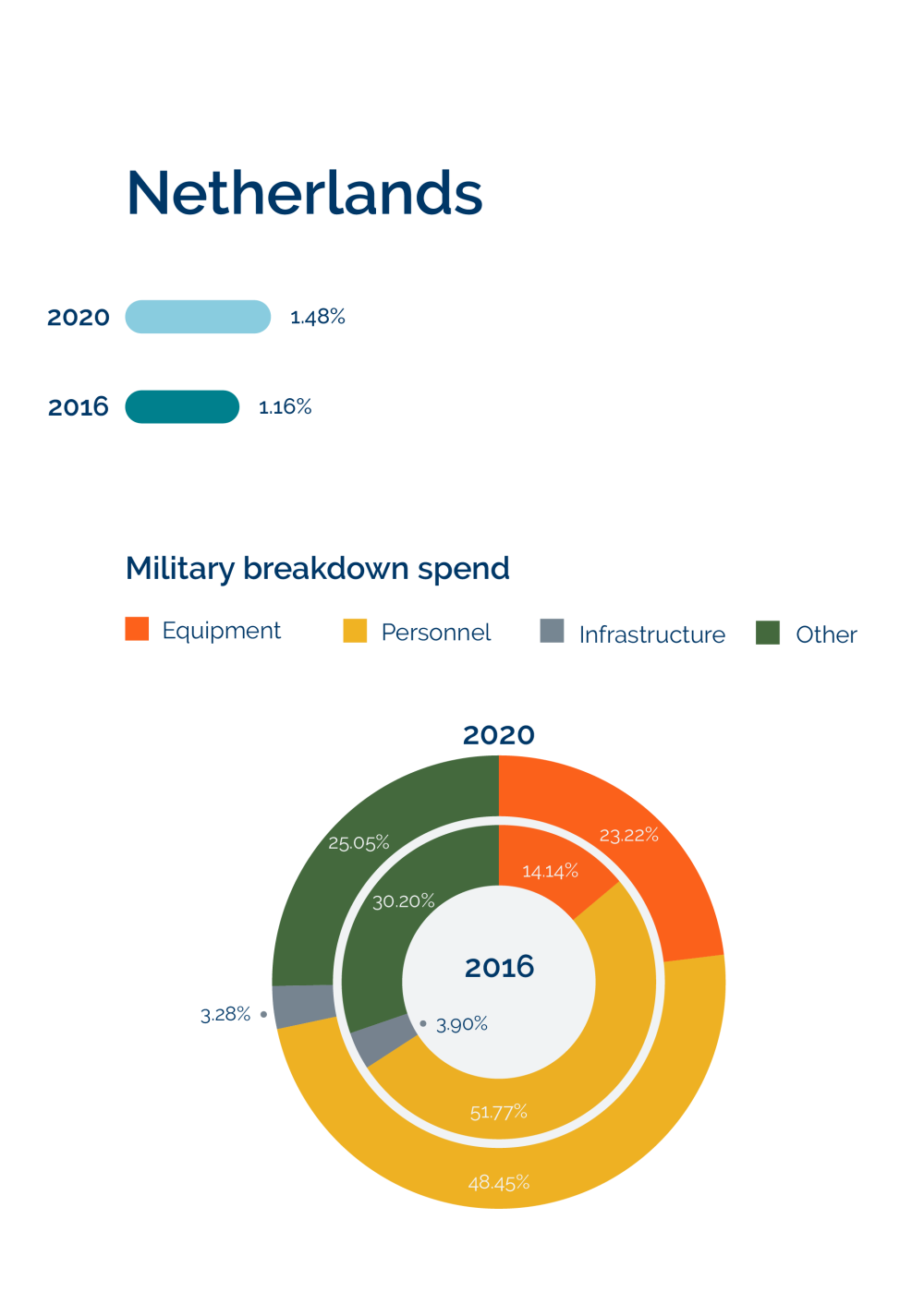

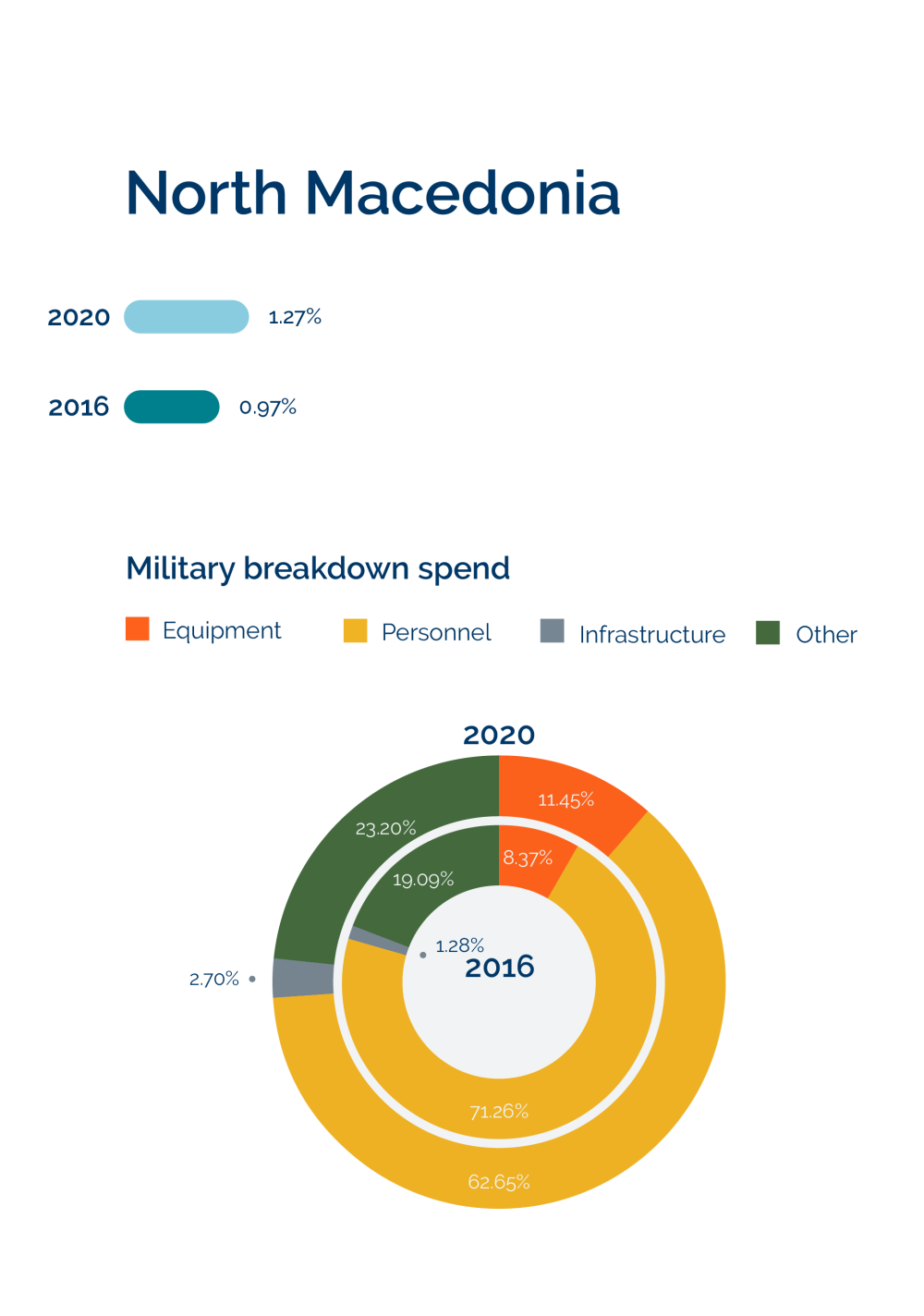

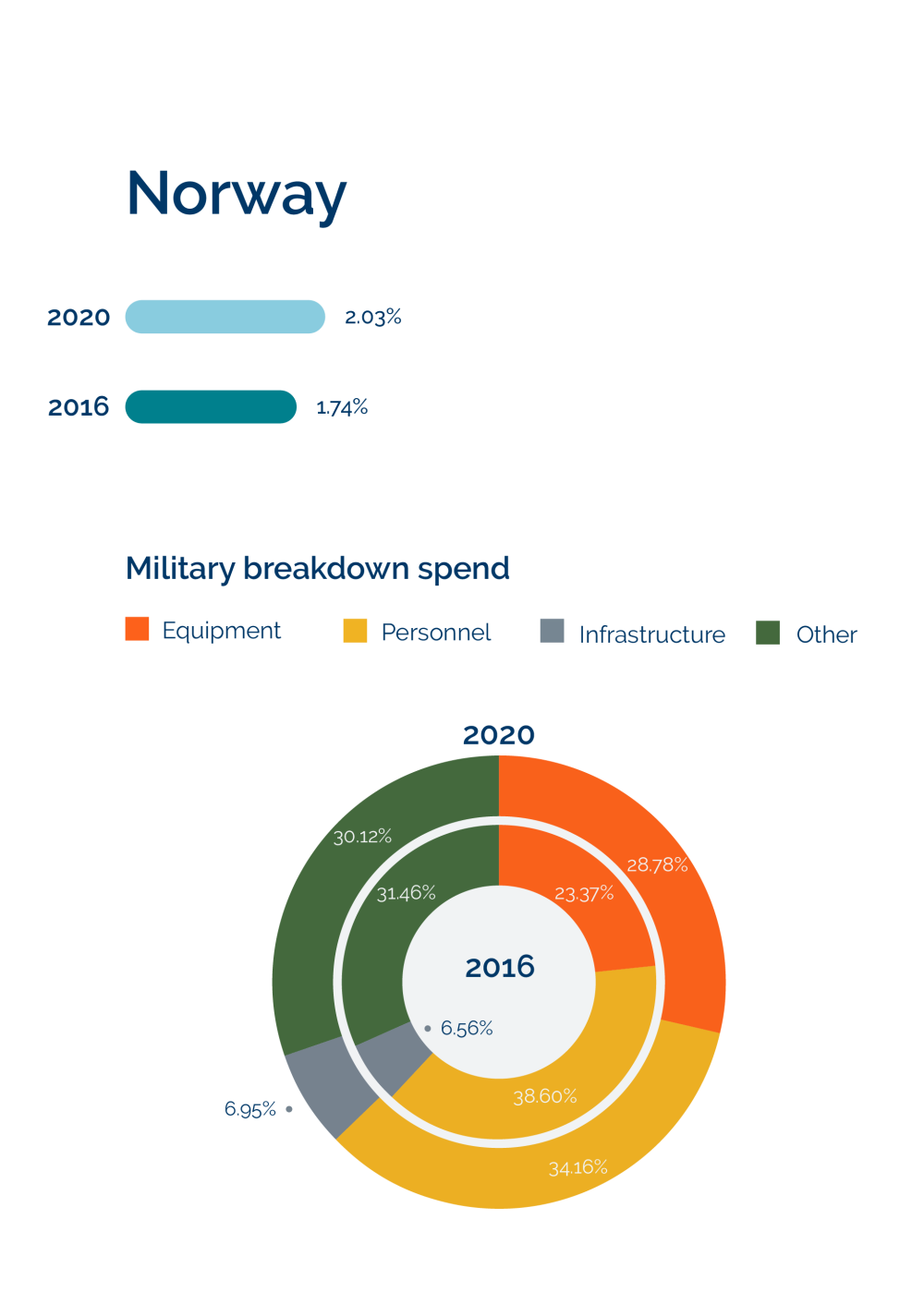

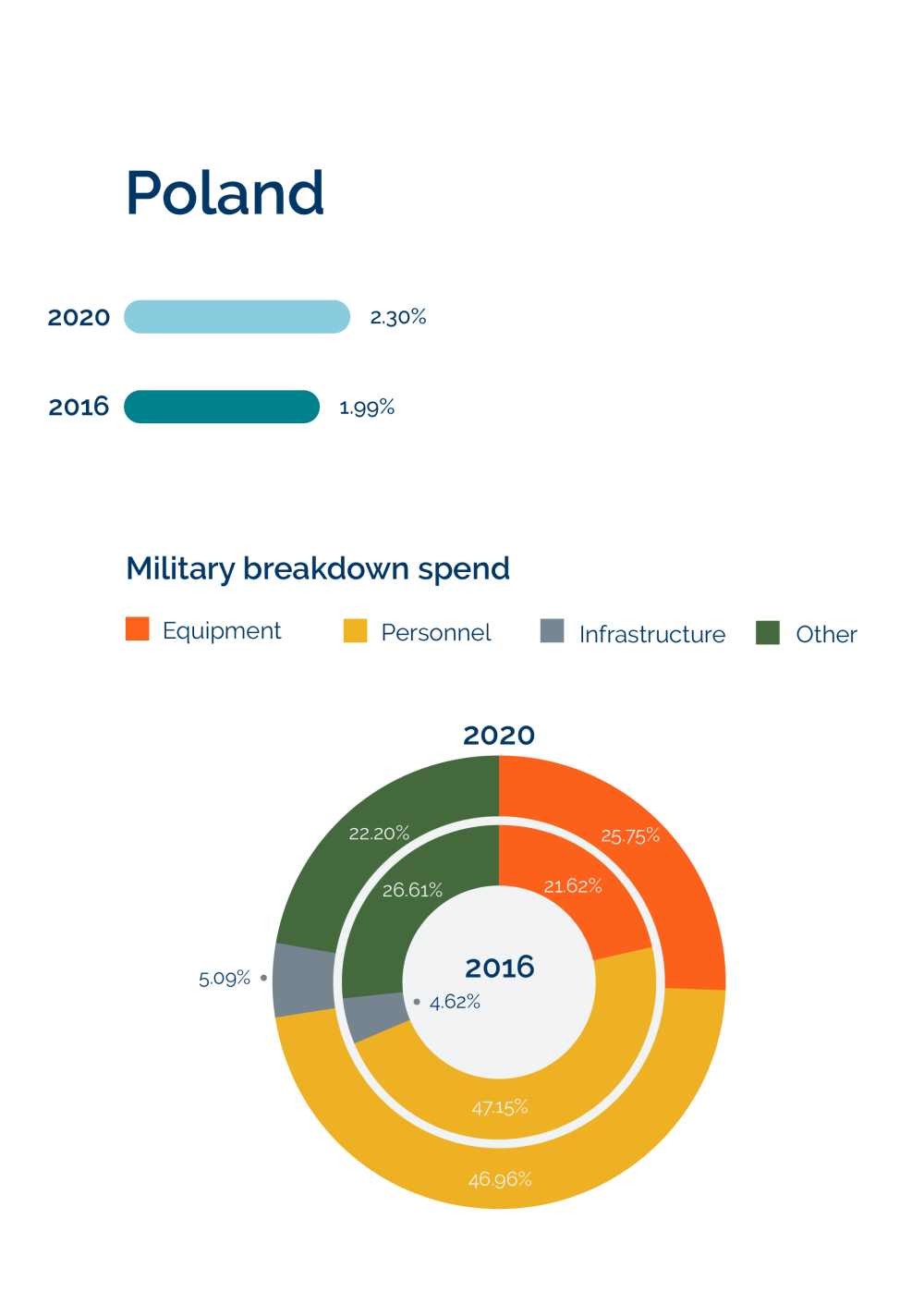

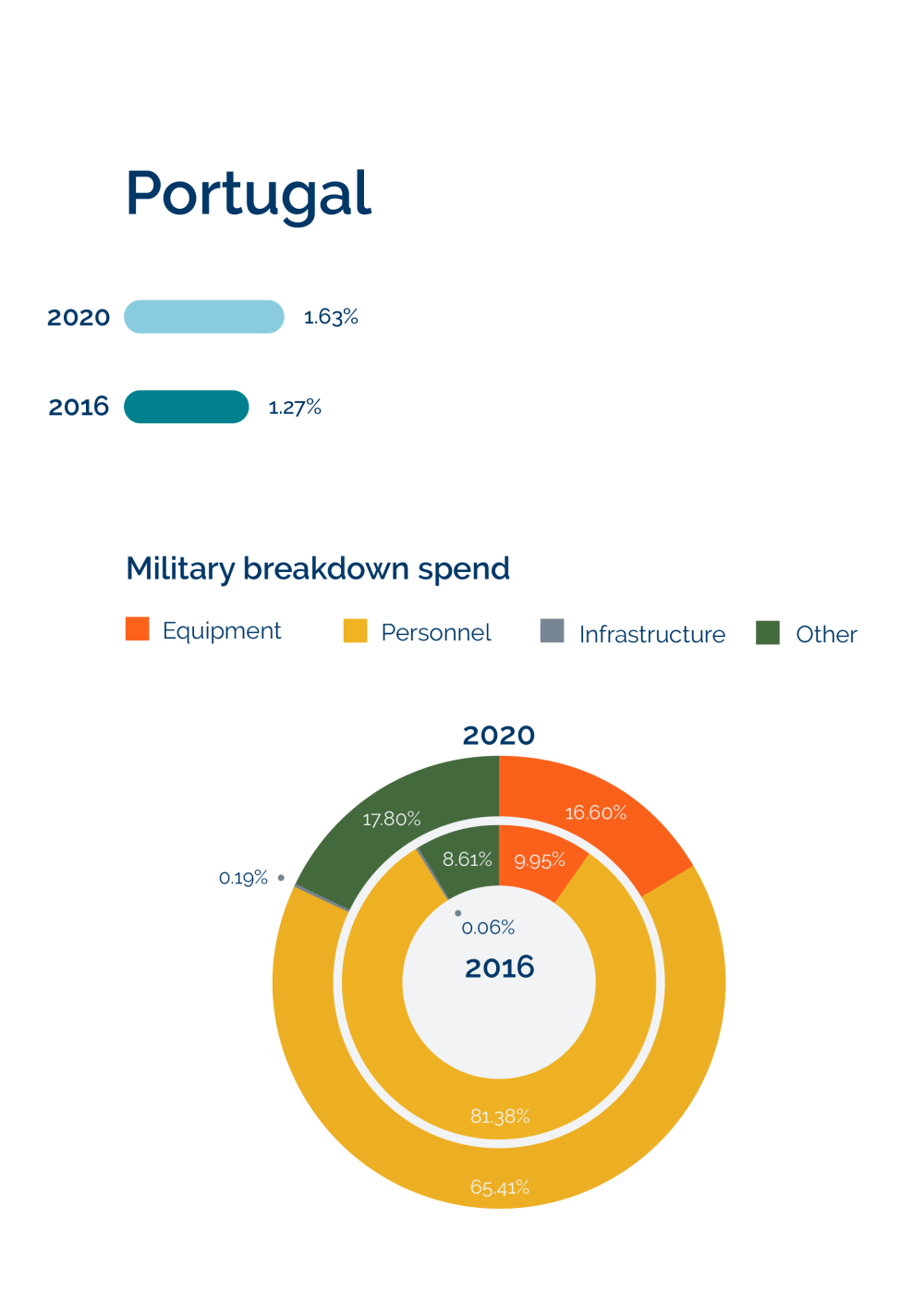

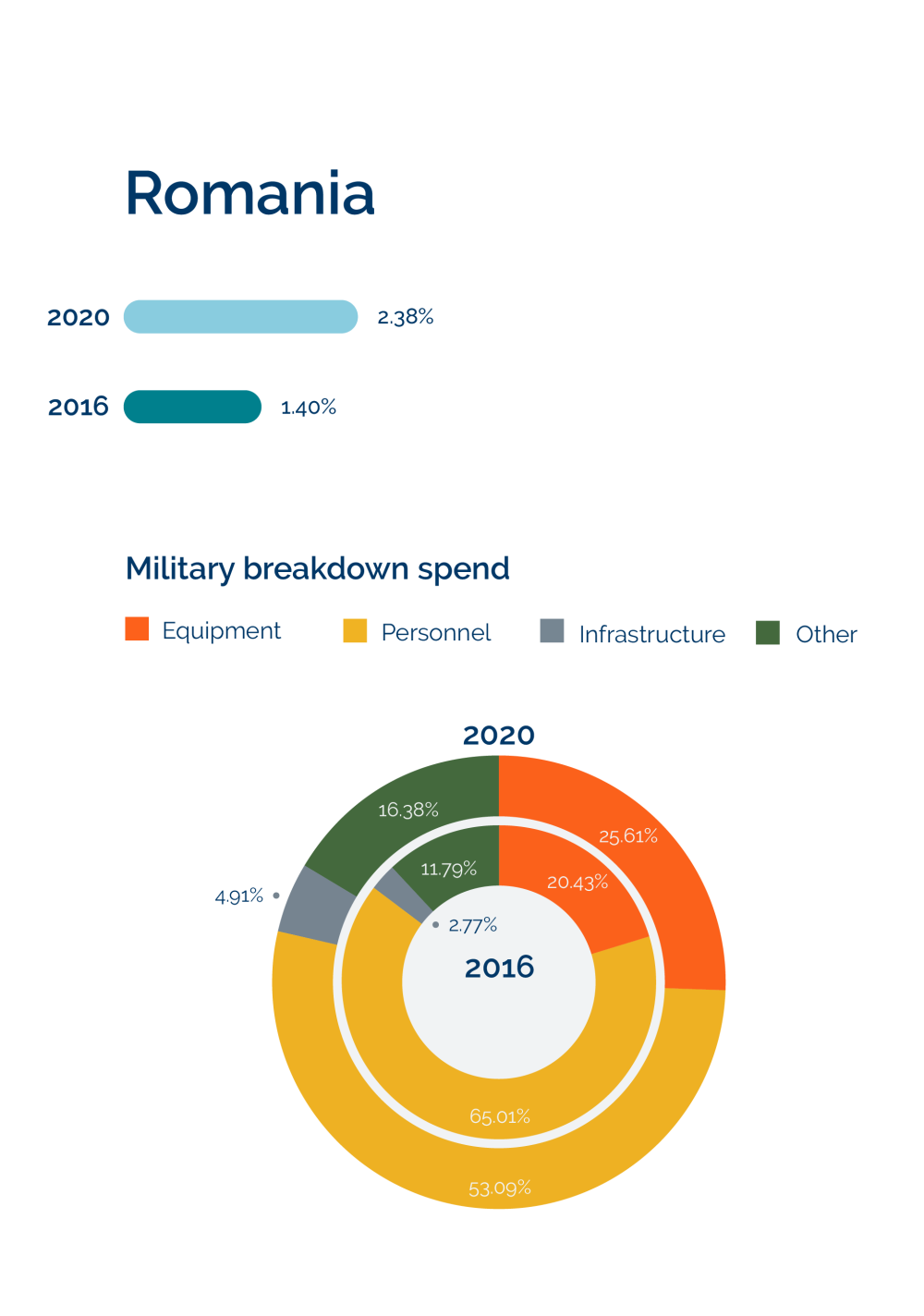

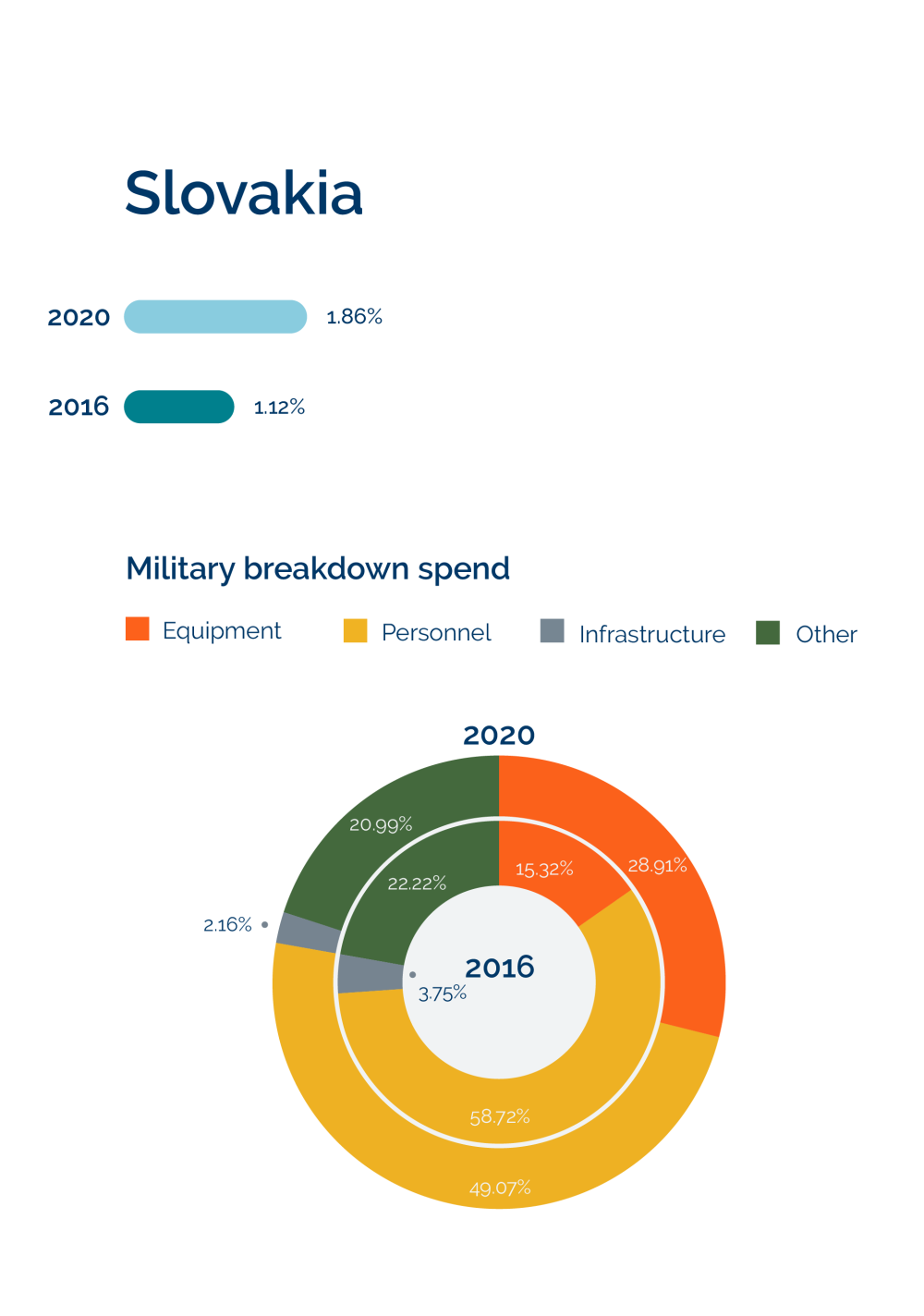

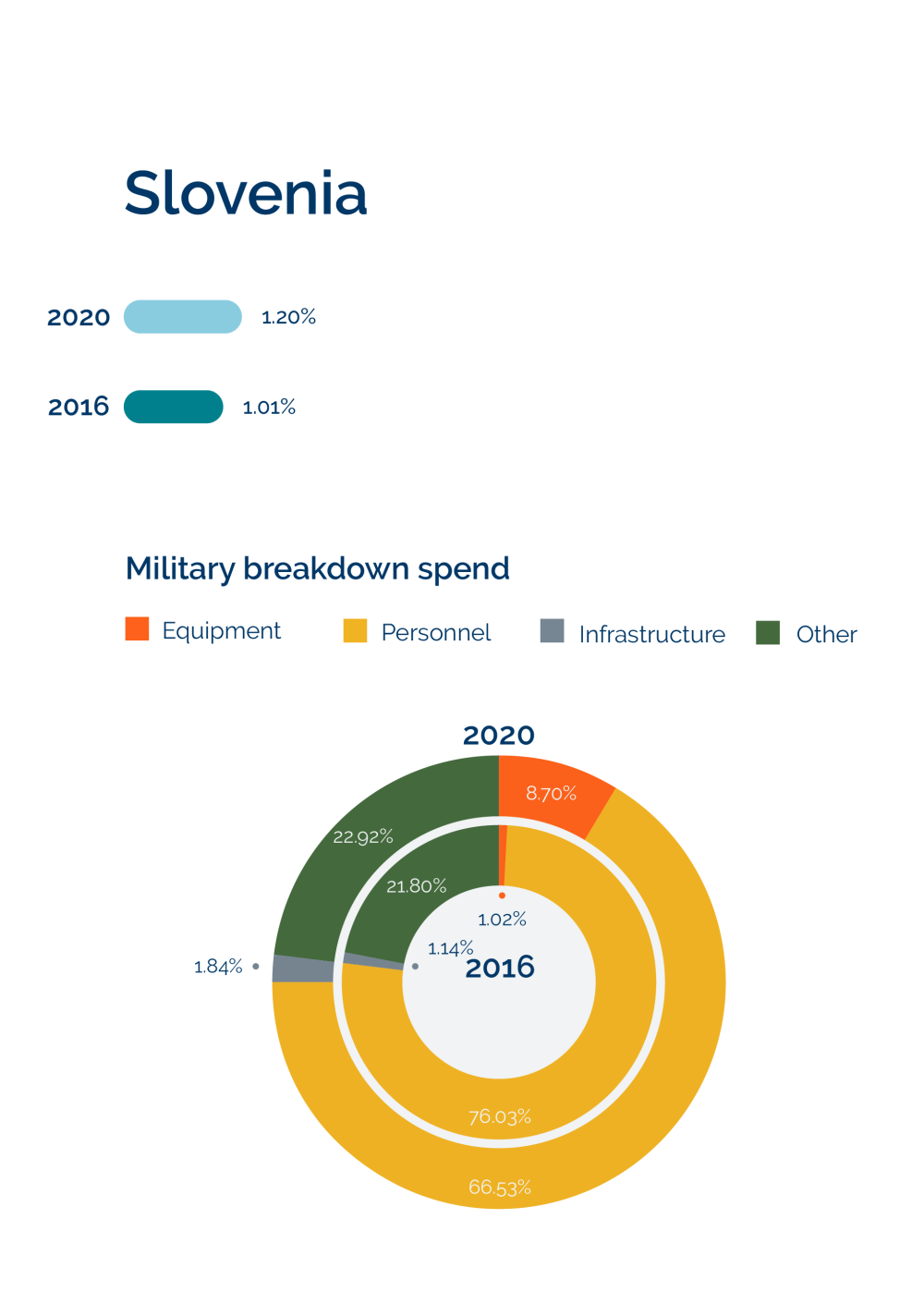

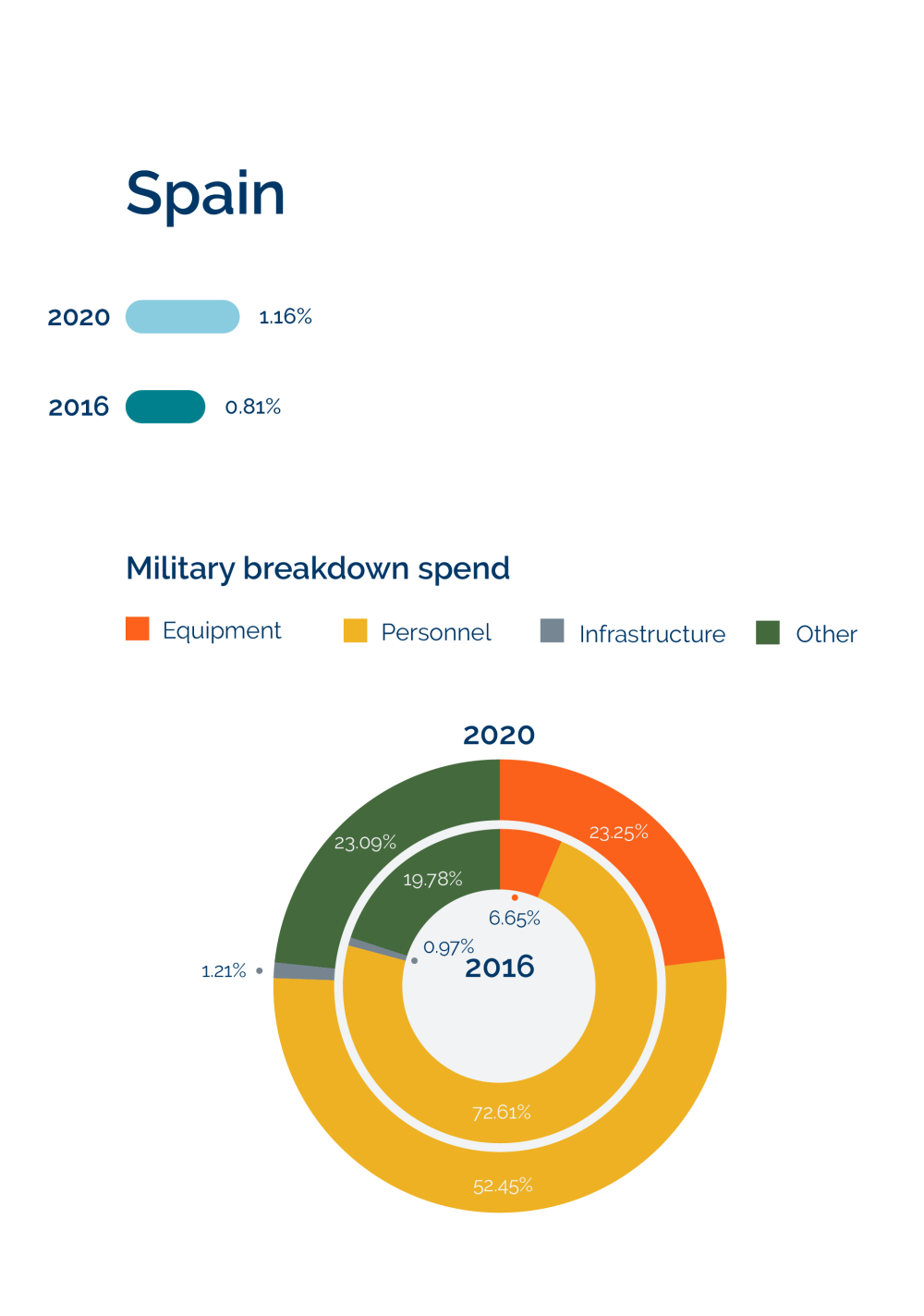

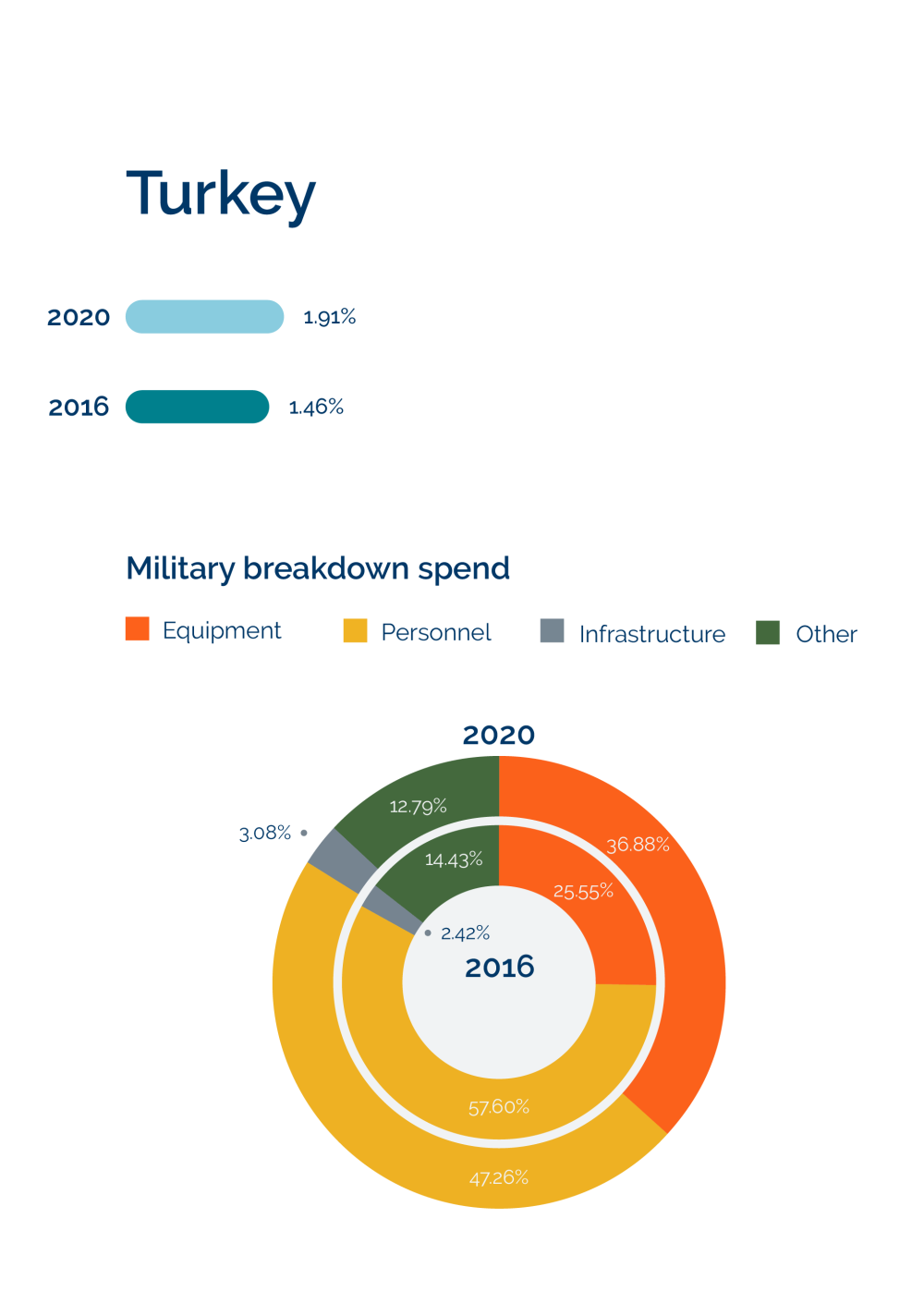

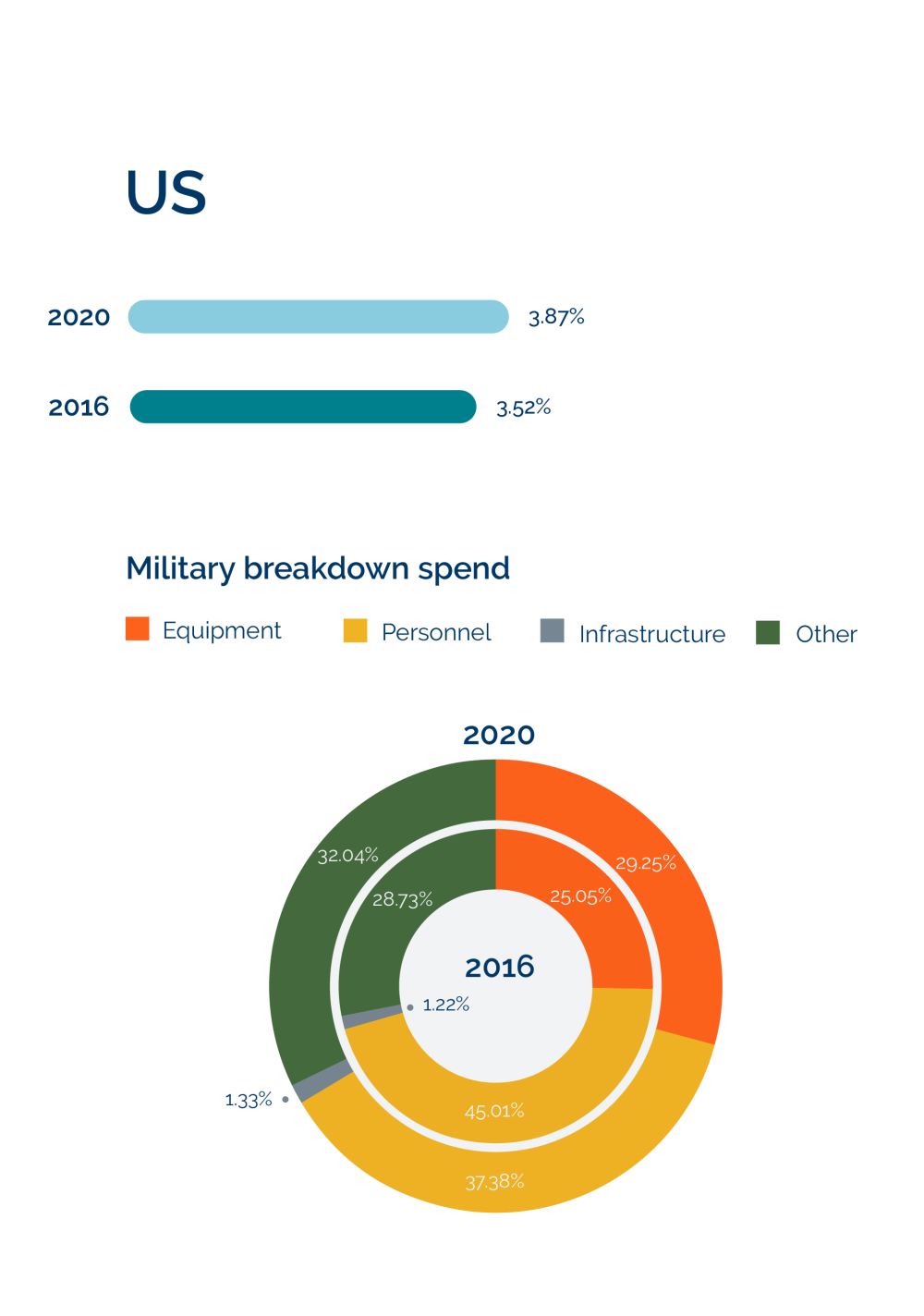

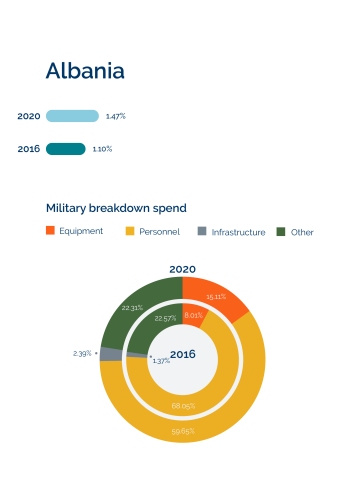

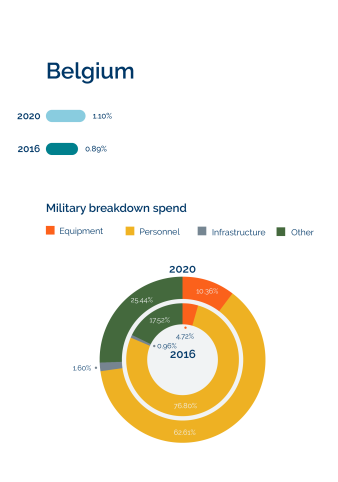

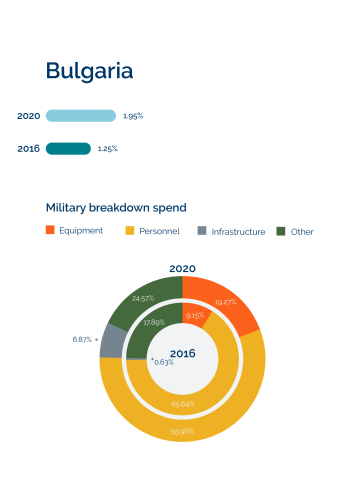

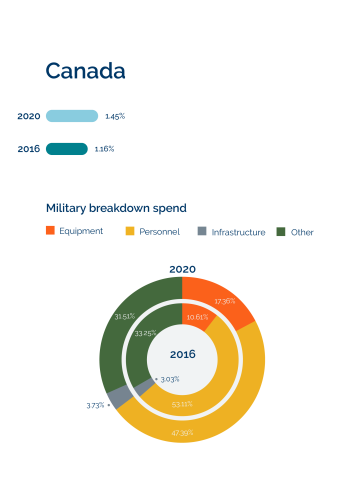

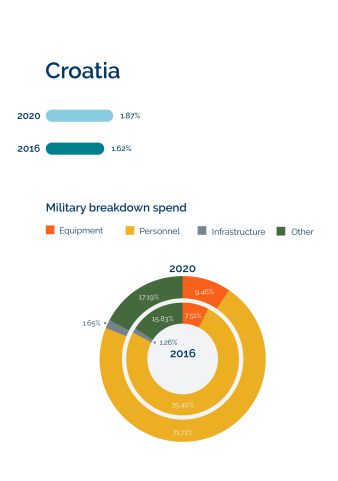

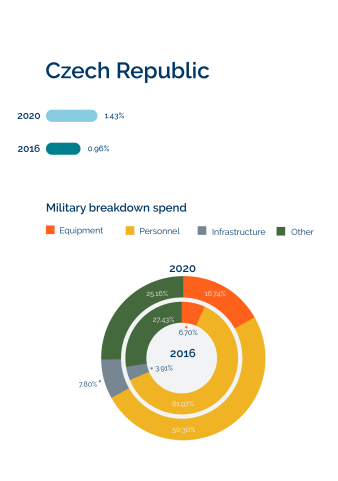

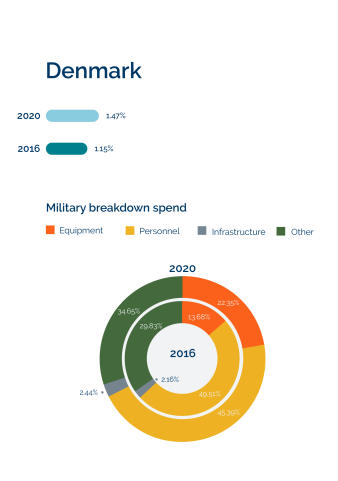

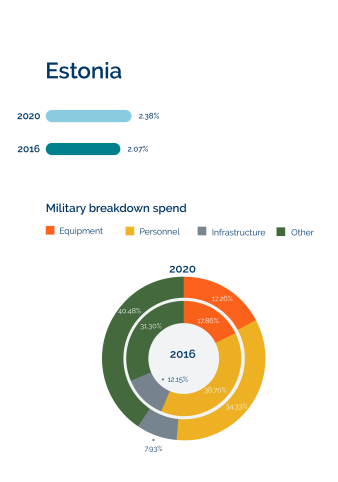

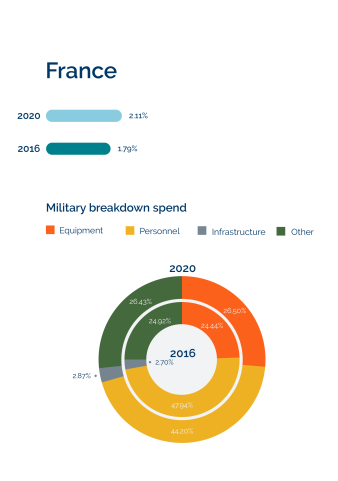

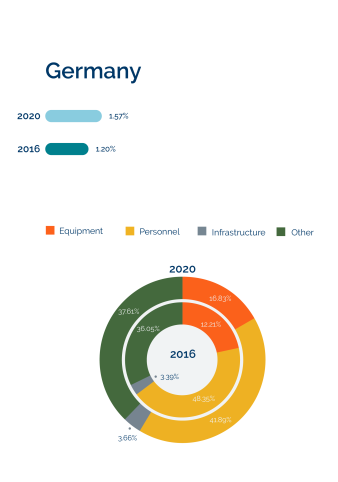

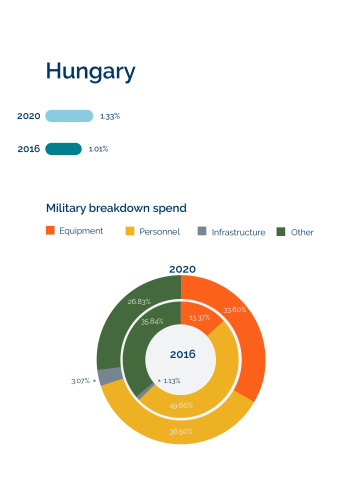

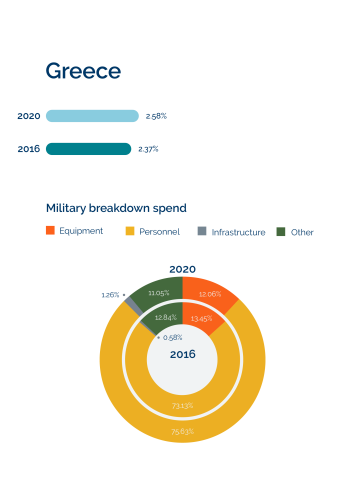

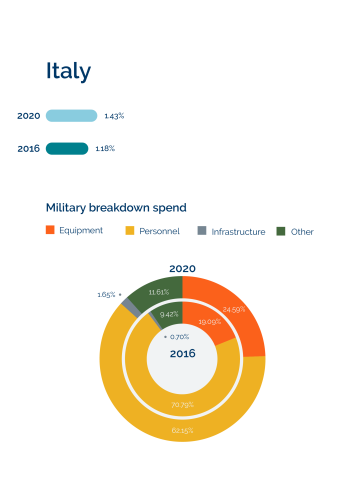

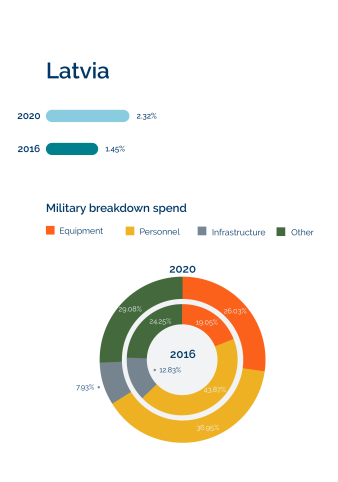

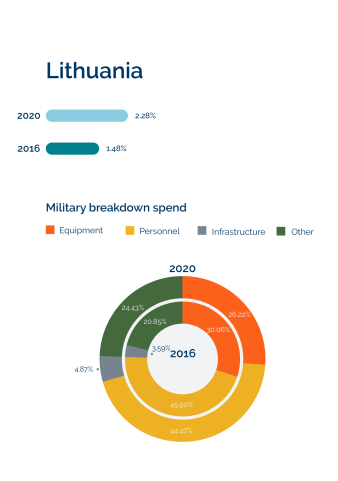

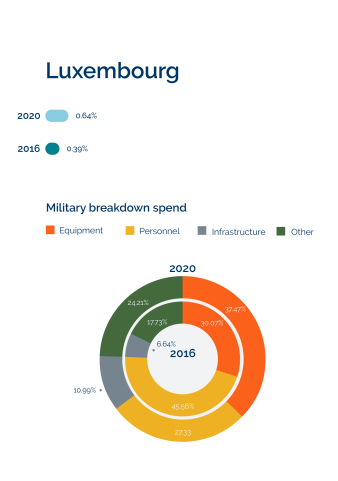

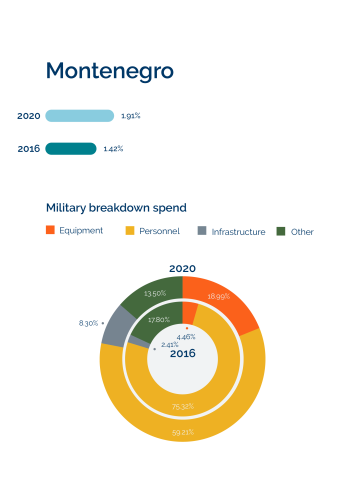

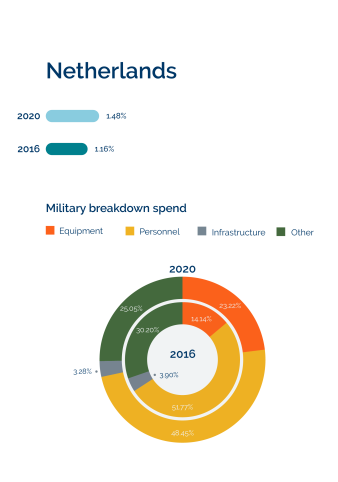

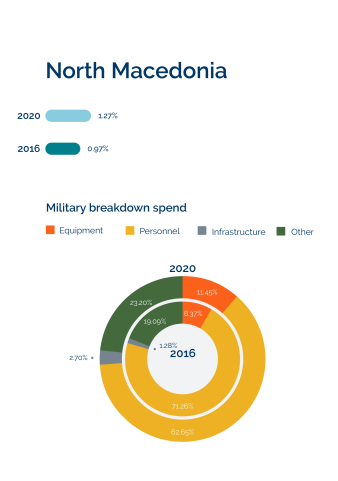

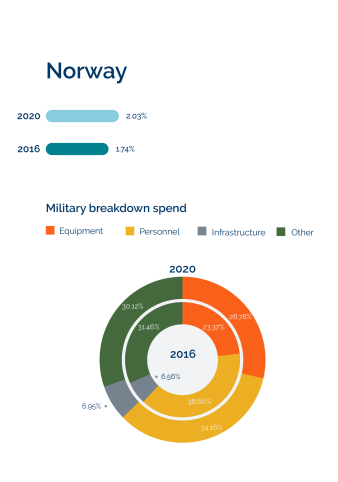

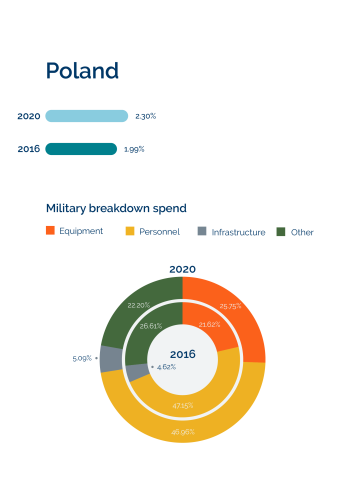

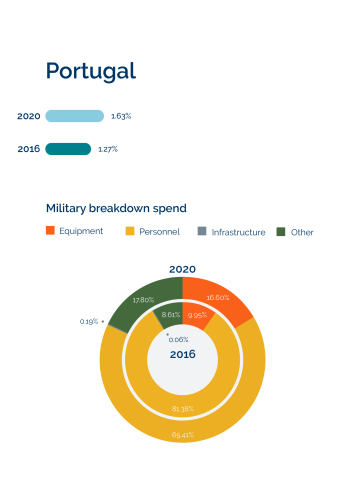

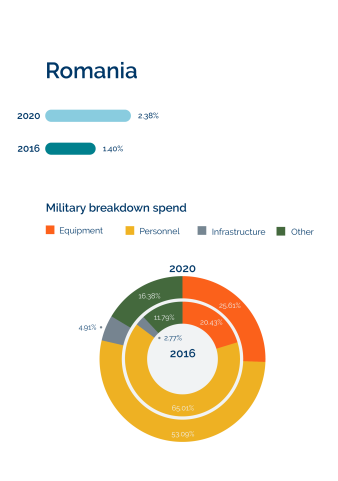

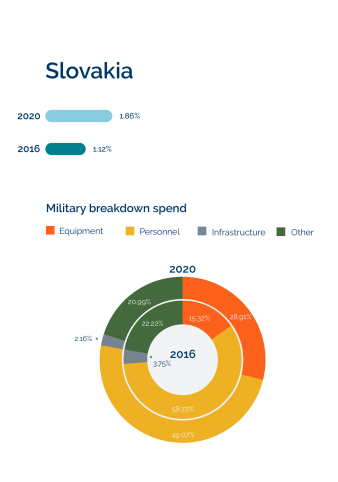

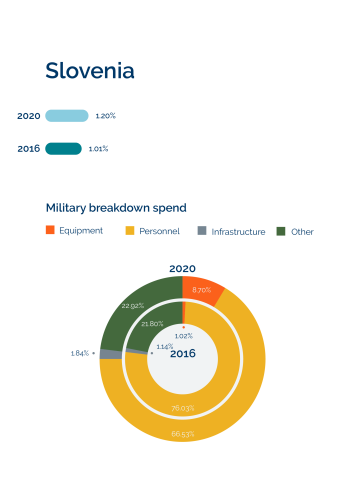

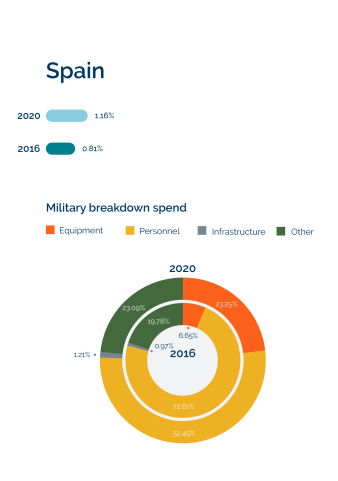

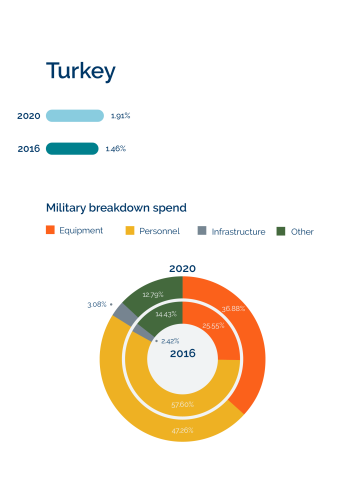

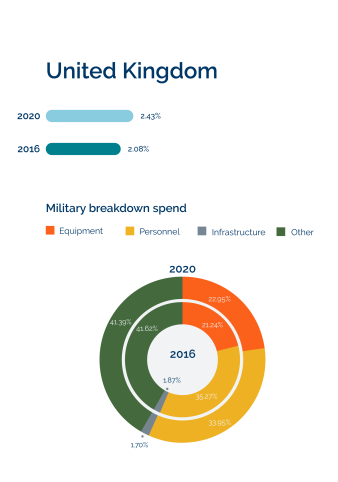

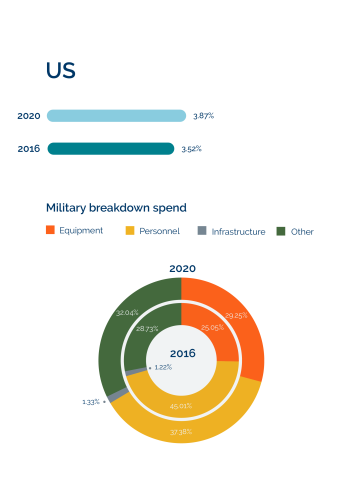

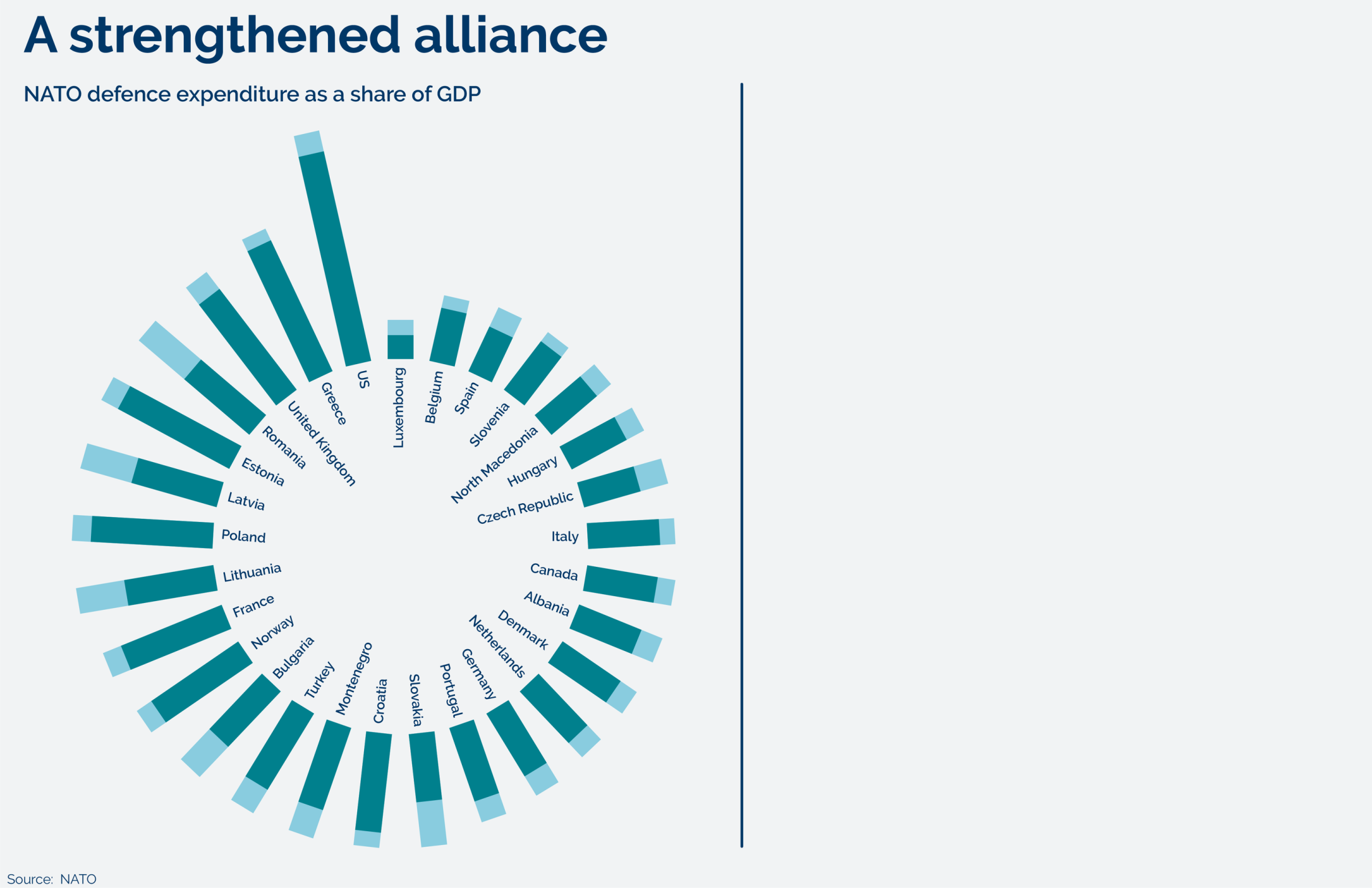

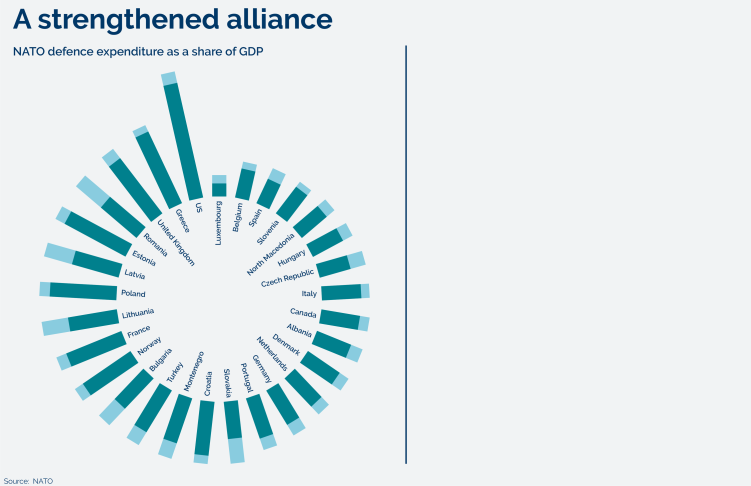

Greater military spending and improved cooperation is likely between NATO members in 2021. All countries in the alliance have increased their defence expenditure over the past four years. This will make it easier for the new US administration to reset its tone and approach to the alliance. But scepticism among some member states about the US as a reliable partner, alongside Turkey’s divergence from the common goals of NATO members, means that efforts to improve military cooperation at an EU-level are likely to continue to make steady progress.

A strengthened NATO

Activists pushing for Catalan independence seem likely to try to reinvigorate their movement in 2021. But we doubt that there will be a return to the mass protests or political crisis that occurred in 2017. Public support for the radical measures they employed four years ago has waned, and with it the willingness to respond to calls for demonstrations and strikes. Obtaining smaller concessions, such as greater devolution and eventually constitutional changes, are more realistic outcomes.

Catalan independence movements

A change in the makeup of the governing coalition in Germany seems probable after federal elections in September. This is likely to lead to a yet more cautious approach by Germany towards Chinese investment in Europe. We forecast that the Green party will probably replace the Social Democratic Party as the junior coalition partner, while the CDU-CSU remains as the main governing party. And that the Green Party’s long-standing scepticism towards the US will also mean it pursues a policy of greater independence from US policy pressure, particularly if the Greens control the foreign ministry.

German federal elections

Forecasts

Outliers

Scottish independence referendum

Monitoring Points

Migration pressures

Disagreements between EU states on how to handle migration would strain any newfound unity in the bloc. As we note elsewhere in this Strategic Outlook, we forecast new and worsening conflicts in parts of the Middle East and Africa. These are likely to lead to an increase in the number of refugees seeking to reach Europe. Countries on the southern periphery of Europe will probably put pressure on other states to take on an equal share of arrivals.

China in Eastern Europe

China has indicated that it intends to re-engage with its 17+1 group in eastern and central Europe. Through this economic cooperation initiative, China has tried to tempt some European states to engage and effectively cede China greater political and economic influence in the region. A failure by China to deliver on investment promises in recent years has meant the initiative has stalled. But we are monitoring new deals for signs that some central and eastern European states are moving back into China’s influence.

Bank failureS

A shortage of liquidity and resulting bank failures would make a failure of cooperation between EU states more probable, and push up the potential for hardship-related protests and unrest. The slowdown in economic activity during the pandemic will have strained the finances of many businesses, making it harder for them to service their loans. The banking sectors of Italy, France, Germany, Spain and the UK seem most vulnerable to the destabilising impacts of this.

Images: David Cheskin; Omar Marques; Louisa Gouliamaki; Luke Dray; Kiran Ridley; Andrej Isakovic/Getty Images

Overall trend: Consistent

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Image: Francisco Seco/Getty Images

for renewal

A burst of social unrest and upheaval is likely in Europe in the second quarter of 2021. But first the region must contend with a period of relative stasis, as most countries remain under restrictions or lockdowns due to Covid-19. Hostile states such as China and Russia are likely to use this time to position themselves to profit from instability when lockdowns are lifted. This would bring a range of operational and strategic risks, from activism and terrorism to governance failures and even the nationalisation of key industries. But at the same time, the EU is likely to find a new sense of purpose amid the crisis.

The European Union appears to see the pandemic as a watershed moment for it to regain a sense of mission, particularly following the lessons of Brexit. We forecast greater harmony between member states in 2021, as they work to defend the bloc against a range of pressures. Economic downturn is likely to preoccupy them the most. But another focus will probably be protecting itself against hostile states, particularly China and to a lesser extent Russia.

The EU and its members states seems likely to make progress on both fronts this year, slowly building its longer-term resilience. We also forecast that EU member states will make gradual steps forward on forming a common security strategy, something the bloc has long lacked. This would also set the region on a longer-term track of asserting greater independence from the US on foreign and military policy, even with renewed efforts for engagement from the incoming Biden administration.

The socioeconomic impacts of Covid-19 are feeding into anti-government sentiment in much of Europe. Large protests and bouts of unrest are most likely in Czech Republic, France, Romania, Spain, the UK, and to a lesser extent Italy. These all had large protest movements before the pandemic, and

their healthcare systems and economies have

been among the hardest hit. There are also signs that there will be an accompanying rise in

activism from anti-liberalist extremists across

the political spectrum.

It will probably only be towards April or May that these movements gain significant traction on the streets. This is partly because of restrictions on gatherings and high Covid-19 infection rates are likely to deter many people from taking part; restrictions and anxieties about the virus should ease with vaccine deployment and warmer weather. But it is also around the spring that we forecast much of the extraordinary state financial support for businesses and individuals will have come to an end. Even with a vaccine and economic stabilisation towards the summer, this is unlikely to have filtered through into improvements in livelihoods.

The prospect of social unrest will probably give urgency to EU coordination on responses to managing the costs and economic damage from the pandemic. There are clear signs that the pandemic has created a new willingness among EU states to cooperate. This involves accepting highly-controversial mutualisation of debt. Given this, there is a strong prospect of the region avoiding liquidity and fiscal crises, and so preventing bouts of unrest spiralling into more severe security or political crises.

The UK is one exception to this. Sitting outside EU financial cooperation efforts, and with the added impact of Brexit and disrupted trade, the UK will probably fail to stabilise its economy this year. A prolonged period of economic stagnation, high unemployment and rising economic disparities seems likely. And with this, there is a reasonable possibility that the prime minister will face a vote of no confidence over his government’s handling of the pandemic, more likely towards the end of the year. A sharp rise in poverty tied with cuts to police budgets is likely to drive crime levels up.

Greater unity among EU member states will come at a political cost. Gaining the cooperation of Poland and Hungary will require the EU to ease its rhetoric on upholding the rule of law. Greater government influence over the judiciary and media in both countries is likely as a result. We also forecast that their nativist ideologies will lead the two governments to seek more control over strategically important sectors, potentially through partial nationalisation. This includes finance and energy.

Uneven application of the law and levelling false allegations are two tactics that the Polish and Hungarian governments seem most likely to use against those that stand in their way of increasing government stakes in industry. And with compromised judiciaries in both countries, legal recourse for those affected will become less reliable. The European Court of Justice is likely to become increasingly drawn into political debate as it remains the ultimate arbiter of legal challenges. But enforcing its rulings will be difficult with a diplomatically cautious European Commission.

The economic and social impact of the pandemic is creating vulnerabilities that states hostile to European liberal democracy, such as China and Russia, can exploit. China in particular seems to be using its economic heft to build influence, such as

by providing loans and embedding itself in European economies. Distressed businesses and government finances will give China more opportunities for this in the coming year. Russia seems less able to pursue such a strategy, so instead will probably continue to rely on blunter approaches such as spreading disinformation.

Image: WPA Pool/Getty Images

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

We forecast a renewed campaign of misinformation and disinformation from both China and Russia early this year, aimed at exacerbating risks around social upheaval and popular discontent over how governments have handled the pandemic.

Protecting its member’s economies from such foreign influence is becoming a greater priority more generally in the EU. We anticipate that some European countries will adopt new approaches in defence of economic and democratic liberalism. They are also likely to give broader application to measures limiting investments, loans and ownership stakes in sensitive sectors from entities with ties to states outside the bloc, aimed at limiting the economic and political leverage of China or Russia in the region specifically.

The implications of greater Chinese economic power in Europe go beyond economic and technological intelligence gathering. Propaganda from China during the pandemic has aimed to undermine public confidence in European governance systems, instead positing the Chinese model as a more effective way to ensure public health and economic stability. We forecast a renewed campaign of misinformation and disinformation from both China and Russia early this year, aimed at exacerbating risks around social upheaval and popular discontent over how governments have handled the pandemic.

There are potential longer-term impacts on governance standards stemming from this foreign interference. China in particular seems to be focusing on central and eastern Europe, where democratic governance systems are less developed. It appears to view these as states as vulnerable and that it can over time turn away from a western democratic model. Countries such as Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia are to varying extents already moving towards a more centralised and autocratic model.

China is likely to struggle to move this much further forward this year, however. In the past couple of years it has lost diplomatic ground in central and eastern Europe, as its 17+1 initiative involving 17 European states has faltered due to a lack of engagement. We forecast that China will try to revitalise this economic and development cooperation group, offering more financing. But with greater economic support at an EU level and tougher regulations on non-EU investment, Europe is slowly becoming more resilient to external and internal threats to unravel the union.

The prospect of social unrest will probably give urgency to EU coordination on responses to managing the costs and economic damage from the pandemic. There are clear signs that the pandemic has created a new willingness among EU states to cooperate.

Click on a country for more information

Forecasts

A change in the makeup of the governing coalition in Germany seems probable after federal elections in September. This is likely to lead to a yet more cautious approach by Germany towards Chinese investment in Europe. We forecast that the Green party will probably replace the Social Democratic Party as the junior coalition partner, while the CDU-CSU remains as the main governing party. And that the Green Party’s long-standing scepticism towards the US will also mean it pursues a policy of greater independence from US policy pressure, particularly if the Greens control the foreign ministry.

German federal elections

Greater military spending and improved cooperation is likely between NATO members in 2021. All countries in the alliance have increased their defence expenditure over the past four years. This will make it easier for the new US administration to reset its tone and approach to the alliance. But scepticism among some member states about the US as a reliable partner, alongside Turkey’s divergence from the common goals of NATO members, means that efforts to improve military cooperation at an EU-level are likely to continue to make steady progress.

A strengthened NATO

Activists pushing for Catalan independence seem likely to try to reinvigorate their movement in 2021. But we doubt that there will be a return to the mass protests or political crisis that occurred in 2017. Public support for the radical measures they employed four years ago has waned, and with it the willingness to respond to calls for demonstrations and strikes. Obtaining smaller concessions, such as greater devolution and eventually constitutional changes, are more realistic outcomes.

Catalan independence movements

Outliers

Scottish independence referendum

Monitoring Points

Migration pressures

Disagreements between EU states on how to handle migration would strain any newfound unity in the bloc. As we note elsewhere in this Strategic Outlook, we forecast new and worsening conflicts in parts of the Middle East and Africa. These are likely to lead to an increase in the number of refugees seeking to reach Europe. Countries on the southern periphery of Europe will probably put pressure on other states to take on an equal share of arrivals.

Bank failureS

A shortage of liquidity and resulting bank failures would make a failure of cooperation between EU states more probable, and push up the potential for hardship-related protests and unrest. The slowdown in economic activity during the pandemic will have strained the finances of many businesses, making it harder for them to service their loans. The banking sectors of Italy, France, Germany, Spain and the UK seem most vulnerable to the destabilising impacts of this.

China in Eastern Europe

China has indicated that it intends to re-engage with its 17+1 group in eastern and central Europe. Through this economic cooperation initiative, China has tried to tempt some European states to engage and effectively cede China greater political and economic influence in the region. A failure by China to deliver on investment promises in recent years has meant the initiative has stalled. But we are monitoring new deals for signs that some central and eastern European states are moving back into China’s influence.

Images: Luke Dray; Stephane De Sakutin; Andrej Isakovic/Getty Images