Image: Pool/Getty Images

The strategic outlook for 2021 is a world that is more unstable, less-cooperative and more prone to crises and conflicts. The coronavirus pandemic has raised the stakes in geopolitics. It has also laid bare deeply dysfunctional relations within and between countries, as well as the state of governance worldwide. The common response to the virus has been containment and control. This is likely to be an apt description for how many governments behave more broadly in 2021.

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Mass vaccination is likely to be uneven and unequal, but it does put recovery on the horizon. Yet as restrictions slowly ease, we forecast that pent up grievances, divisions and disputes are liable to erupt. Tides of civil disquent are reasonably foreseeable and tight political control is a likely response in many regions. Nationalism, authoritarianism and populism have resurged in global politics in recent years, and we forecast that this trend will persist if not intensify in 2021. Self-interest and unilateral action is liable to be the simpler and prefered mode of action.

Economic, social and political crises on such a wide scale could hasten major changes to the ordering of the international system, heralding a new era of power balancing. For many years in Strategic Outlook we, like many others, have warned that the global order is becoming less multilateral and more anarchic and competitive. The pandemic has shown just how much the capacity for multilateral cooperation between states has eroded when the need for it has never been greater to maintain peace and prosperity.

The risk of interstate disputes and conflicts in 2021 is likely to rise towards levels unseen in decades. Relations between the most powerful actors in the international system are at their lowest ebb since the Cold War. The most significant deterioration and the greatest geopolitical risk is between China and the West, particularly the United States. Relations between Russia and the West are mired in mistrust and hostility. Strategic competition between China and India is rising sharply. Arms control is at a historic low, while defence spending is rising. And rivalries among lower-order powers are festering, with responsible mediation of conflicts as absent as regional meddling is often obvious.

Geopolitical fault lines

In this more adversarial landscape, new geopolitical fault lines are emerging and old ones more liable to flare. War between the US and China is still improbable, as is war with Russia. But intensifying competition between the three, particularly the US and China, is unsettling the global balance and making crises involving second and third tier powers more likely.

Frozen conflicts, contested territories, and regions deep in crisis are where power struggles are most likely to play out in terms of military action. Nagorno-Karabakh, Donbass, Kashmir, Ladakh, Western-Sahara, The Sea of Azov, and the Taiwan Strait are just some of the flashpoint regions to watch in 2021. All have the potential to draw in outside competing powers.

At the same time, the erosion of the rules-based multilateral order will continue to make efforts to fight the pandemic less effective than it could be. But it carries deeper geopolitical risks. The Trump administration’s wavering commitment to security guarantees, alliances, trade agreements, international rules and democratic governance, has left smaller countries feeling vulnerable and isolated at a time when they need external support to recover from the pandemic. In some cases this is prompting positive action by such countries to respond to this, notably with greater unity and cooperation between European Union member states.

Reversing this trend of fragmentation on a global level may be impossible. As the US has retrenched and the credibility of its deterrence waned, adherence to the rules in international relations has declined. Bilateralism and unilateralism are the inevitable successors to multilateralism; both favour more powerful self-interested actors and both surged in 2020. This makes global risks – like conflicts, pandemics, migration, proliferation and climate change – much harder to manage. In the meantime, the options smaller states have for financial aid in a post-pandemic world are limited and China is well placed to extend its influence in almost every region.

The Trump administration’s wavering commitment to security guarantees, alliances, trade agreements, international rules and democratic governance, has left smaller countries feeling vulnerable and isolated at a time when they need external support to recover from the pandemic.

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

As mass vaccination programmes help countries re-open for business, measures to contain the coronavirus will slowly ease. But vaccines themselves are likely to be as much a source of political rivalry as they are a solution for the most profound global risk the world has experienced in decades. Rather than binding the world together in common cause, the coronavirus crisis has had the inverse effect. Discord and vulnerabilities in a global system of complex interdependencies have been exposed. The world will not be the same as it once was.

Pandemic fallout

Image: Antonio Masiello/Getty Images

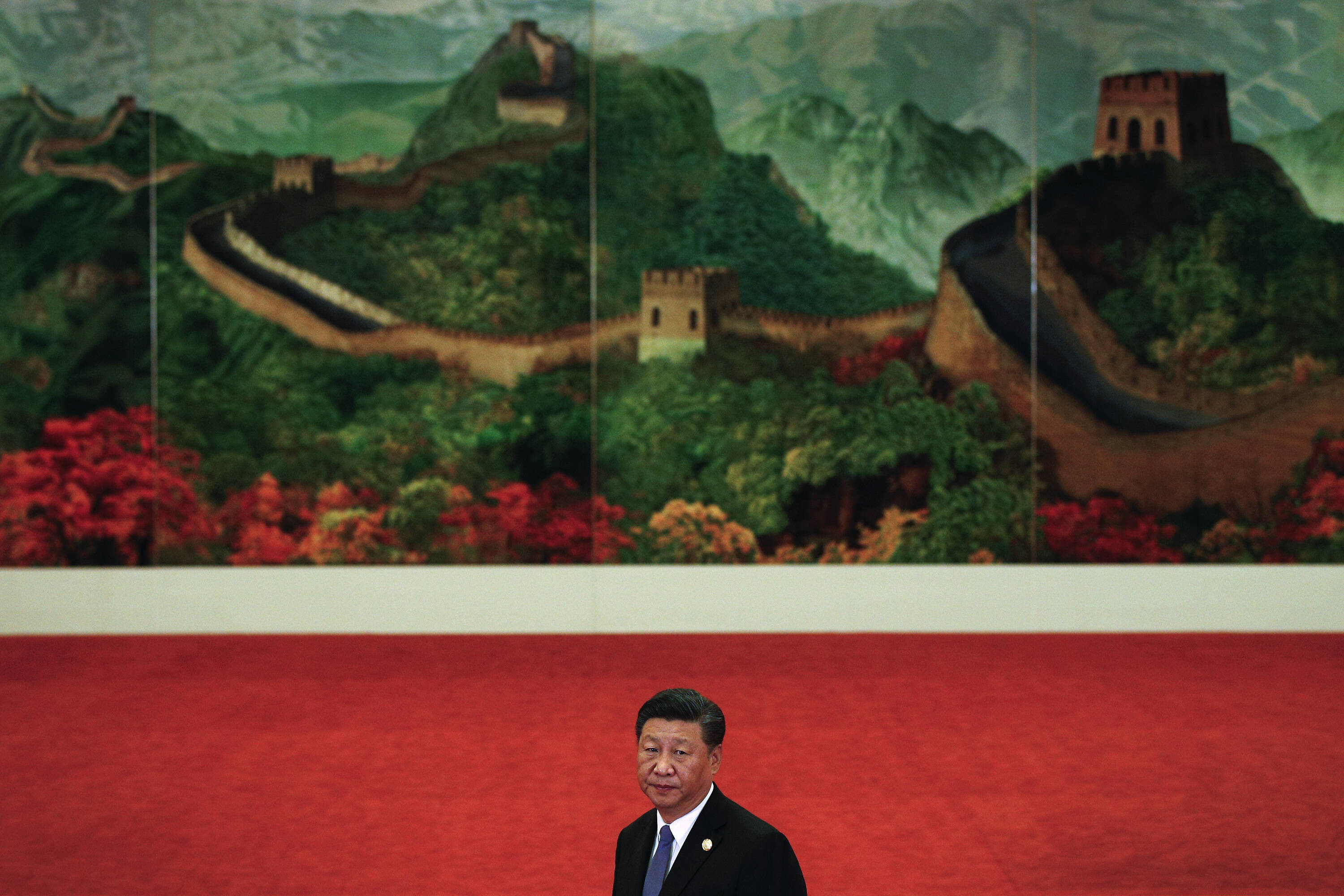

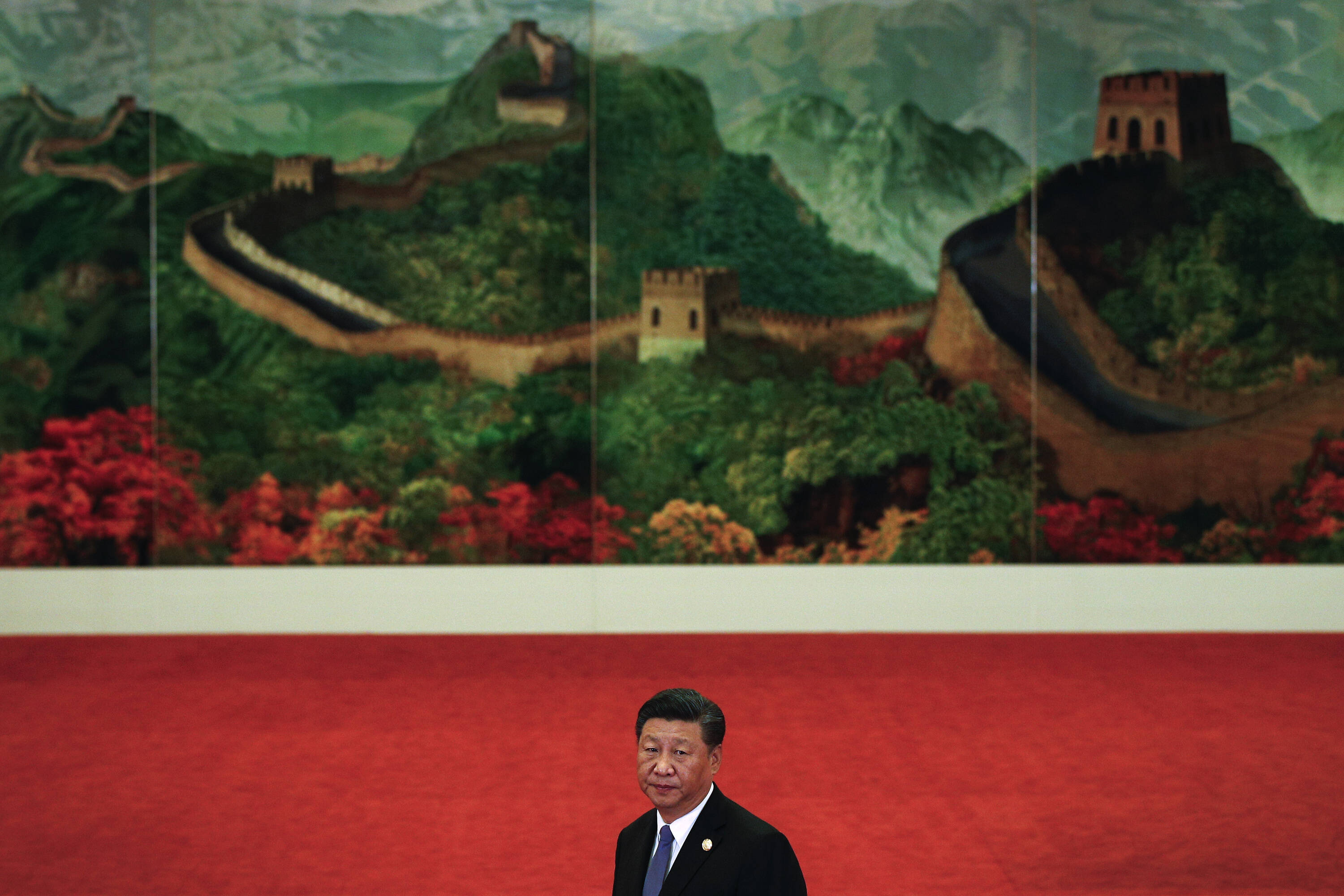

China’s grand strategy

Understanding China’s grand strategy as well as its tactics is key to understanding geopolitical risk in 2021 and beyond. Simply put, China’s goal is to become a high-tech global superpower that is self-sufficient in its manufacturing capability, and is also able to preserve its territorial integrity while ‘re-unifying’ its claimed territory. The latter requires acquiescence. The former requires assured control of global supply chains and markets to ensure growth, future dominance, and innovation-driven development. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 policy is emblematic of its goals and the centrality of self-sufficient technology manufacturing in its strategy.

The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s signature policy that furthers this strategy through infrastructure investment and development across Asia. The BRI enables Beijing to project greater economic and political power and influence by ultimately transforming beneficiary states in its path into dependent clients. China has also created a parallel and alternative system of international institutions and treaties to those led by the US, such as the Shanghai Pact. These are vehicles for Beijing to advocate the superiority of its own brand of autocratic governance, secure its influence and posture China as an alternative global leader.

For Washington’s policy makers, China’s strategy represents an existential threat to America's global standing. The competition over industry, trade, the security of supply chains, and access to markets and commodities are critical for long-term economic growth and security for both sides. The competition is likely to become more adversarial in 2021, even with a new administration. For China, it is a zero-sum game for dominance played out through a mixture of investment, coercion, co-option and control, often prosecuted through cyber action to gain advantage. For the states in its path, refusal to at least partially bend to China’s will is rarely an option.

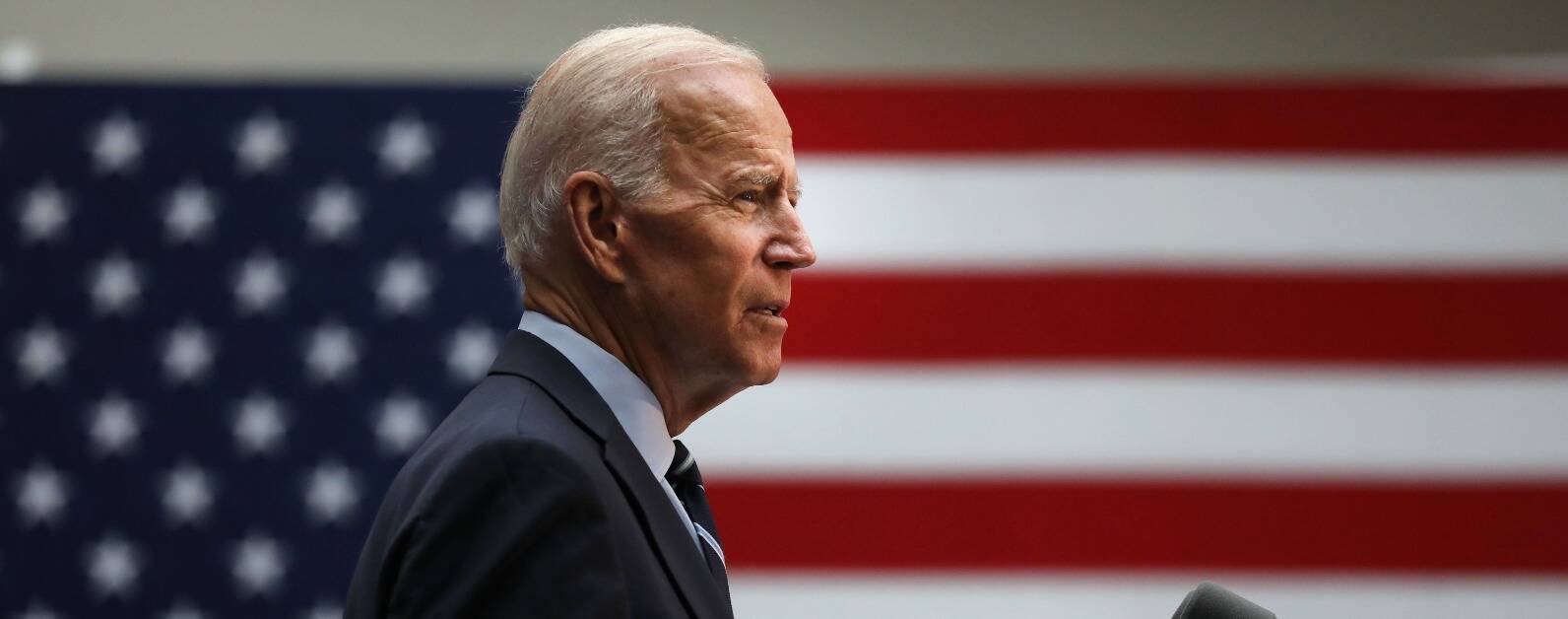

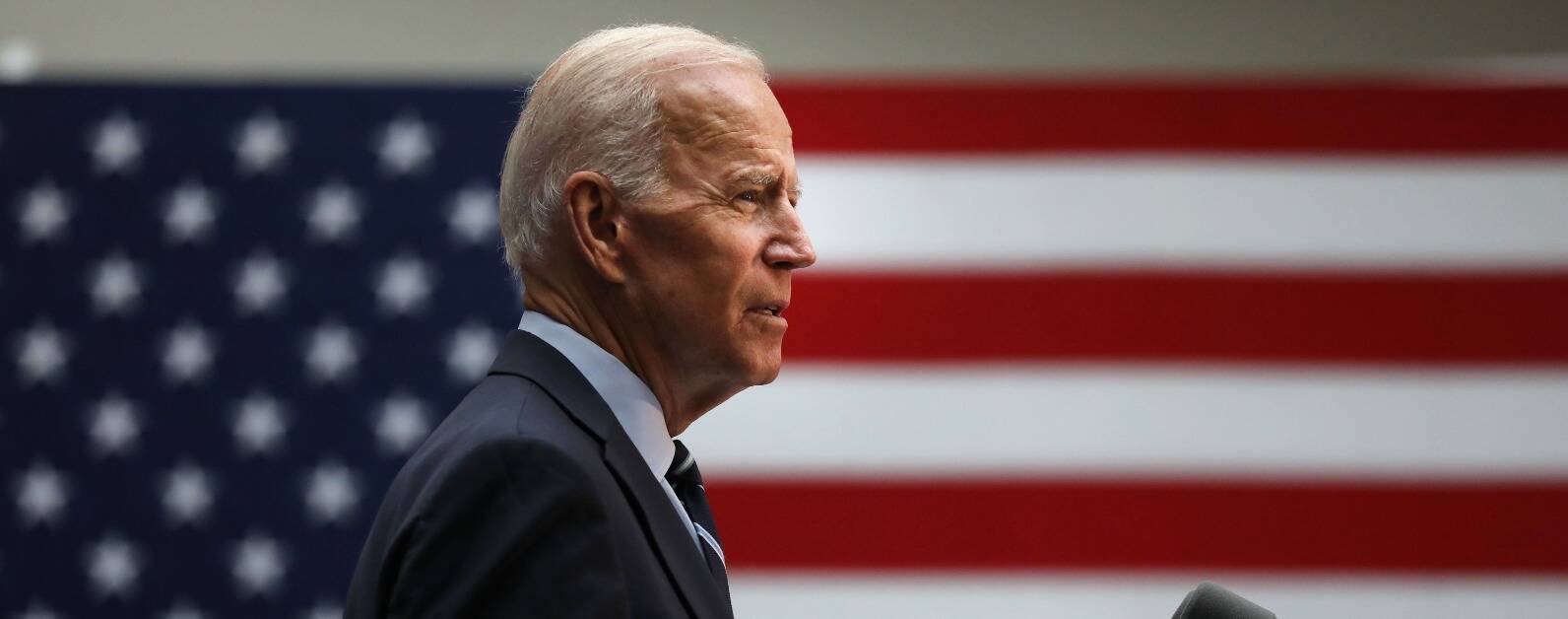

The Biden administration has pledged to rebuild relationships and US standing. But it is unlikely to recover much lost ground and trust in 2021, and it will struggle to counter China’s political advance. Reasserting US commitments to multilateralism, not least the World Health Organisation and the Paris Climate Accords, are very likely early on. But this is unlikely to substantially restore the effectiveness of supra-national institutions in regulating state behaviour.

The most urgent problems Mr Biden faces are complex and require concerted diplomacy and robust action. His first orders of international business include responding to the Russian hack of SolarWinds, curbing the Iranian nuclear programme, and countering and containing an increasingly assertive and ambitious China. The new president’s ability to count on others and succeed in these policy areas will be limited.

Reasserting leadership

The Indo-Pacific region is likely to be where the consequences of Sino-American rivalry are greatest. It is there where China has become more confrontational, coercive and controlling, and confident in being so. We forecast a raft of tensions and crisis points on China’s periphery, from Central Asia, along the Himalayas to the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea.

Beijing appears more intent on pursuing territorial claims that we have seen in years, and using ‘hybrid warfare’ methods to create crises and a sense of international urgency to matters on its agenda. A trade spat with Australia in late 2020 is one of the more overt glimpses of how robust Beijing is becoming in initially trivial disputes, and how willing it is to single out countries and test the strength of their alliances.

It is in this context that the US-China rivalry is the top geopolitical risk in 2021. Unlike the US, China has yet to militarily intervene abroad to safeguard its interests. This is probably just a matter of time as its economic surface area grows and renders it ever more exposed to threats. But its fast evolving military capabilities point to a growing will to exercise hard power in theatres where it has a long-term interest in deterring those that might seek to resist its ambitions.

The Trump administration’s ambivalence to shoring up traditional alliances and promoting democracy among smaller states was at odds with confronting China’s grand strategy. But like its predecessor, the Biden administration will probably see India as its key economic partner to counter China economically in Asia. This adds a new and uncertain dynamic to regional competition in Asia, as well as to conflicts and disputes in which all are stakeholders, such as in Afghanistan and the contested regions on India’s northern borders.

It is not only in the Indo-Pacific where geopolitical risks are rising. US retrenchment from the Middle East has accelerated a trend of instability and rebalancing in a region where it has traditionally underwritten deterrence and meditation. Beyond the persisting tensions between Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel, new dynamics threaten to keep the wider region in a state of strategic overload. A potential Saudi Arabia-UAE-Israel axis on one hand and Turkey-Qatar axis on the other is important to watch as a dynamic that puts weaker states in their orbit into more uncertain positions over a growing divide.

This new dynamic makes any US attempt to draw Iran back into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action to curb its nuclear ambitions less likely to succeed. But it also makes Mr Biden’s ability to help stabilise the region even harder. Competing powers in the region have already played a hand in conflicts from Libya to Nagorno-Karabakh to Syria. Iran and Saudi Arabia, as the two most hostile powers in the region, are at growing risk of open confrontation as new technologies increasingly enable their proxies to carry out actions that risk drawing them into direct conflict and crisis.

Turkey and Saudi Arabia in particular are two states to monitor as they reposition themselves as dominant players, challenging the status quo and perpetuating disputes in neighbouring countries for economic and geopolitical gains. Their ambitions and behaviours are increasingly in tension with their traditional alliances with the West. This is yielding yet more uncertainty and complexity over how future security, democracy and stability in the wider region is deliverable any time in the future.

The frontlines of competition

In the struggle for geopolitical dominance where the stakes of open confrontation are high, every actor is a pawn in the struggle for control of information and its integrity, of revenues, of supply, and of influence in public discourse.

For many global businesses and other organisations, the risks arising from this burgeoning first and second-order power competition are not only limited to unstable regions or the traditional domains of geopolitics. The front lines permeate the global economy, trade, supply chains, markets, workforces, our collective ideas, and indeed the very fabric of our societies. Cyberspace is the principal battlefield where, unlike the conventional physical space, deterrence and the rules of engagement remain poorly defined. If the international system is becoming more anarchic, the cyber system is far more so and has growing potential to yield real-world crises that affect daily lives

and stability.

Businesses themselves are on this non-kinetic front line as vectors and targets, a warning we made in Strategic Outlook 2020: The New Political Risks and reiterate again. In the struggle for geopolitical dominance where the stakes of open confrontation are high, every actor is a pawn in the struggle for control of information and its integrity, of revenues, of supply, and of influence in public discourse. Businesses should not underestimate the urgency of the threat and the role they play as actors in this strategic and divided landscape.

Hostile state activity targeting businesses is already surging, and we anticipate this to continue worldwide and take new forms in 2021. China’s strategy of accelerated growth and technological autarky requires the acquisition of trade secrets and intellectual property, obtained by espionage, regulatory compliance in its jurisdiction, or simple acquisition of companies. It also requires control of political narratives, which can be obtained by the same means or simply by coercion as is now its wont. Global corporations are not exempt and should anticipate pressure from all sides to take sides.

Such efforts by Beijing – and indeed other actors such as Russia – to further their ambitions and maintain control at home and abroad are global in scope. From a corporate standpoint they demand greater integration between risk management functions at the highest levels of corporate governance for any organisation wishing to trade in jurisdictions that span geopolitical rivalries. They also require risk management from the core to the periphery, from head office to the vulnerable underbellies in the global supply chain. Africa is likely to be one such arena where cyber security gaps are potentially significant in attempts to harm Western economic interests for strategic gain.

The non-kinetic battlefields

The pandemic has been remarkable insofar as lockdowns and restrictions have created a sense of hibernation and stasis. But in our analysis, it is merely a pregnant quiet. Every country in the world has been rendered economically and politically vulnerable, as has nearly every global business. The potential for regeneration and positive change is immense, but so too is the potential for change wrought by those that wish to bring about new realities that better serve narrow self-interests.

Economic and political liberalism in particular are in peril of losing ground. Both rely on a trinity of trust, common rules and cooperation to yield their promised dividends of peace and security. In the profoundly unstable world the pandemic has created but is yet to be fully revealed, these virtues may not hold much currency. Global security and stability in 2021 will therefore probably depend more on containment and control of all risks until a new semblance of order solidifies. This is not a liberal outlook, but a realist one. Knowing how to navigate such a regressive world, or even prevent it, requires imagining this future and considering strategic warnings such as this sooner rather

than later.

A post-pandemic world

The potential for regeneration and positive change is immense, but so too is the potential for change wrought by those that wish to bring about new realities that better serve narrow self-interests.

China’s goal is to become a high-tech global superpower that is self-sufficient in its manufacturing capability, and is also able to preserve its territorial integrity while ‘re-unifying’ its claimed territory.

Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Image: AFP Contributor/Getty Images

Image: Tauseef Mustafa/Getty Images

Image: Bill Wechter/Getty Images

The strategic outlook for 2021 is a world that is more unstable, less-cooperative and more prone to crises and conflicts. The coronavirus pandemic has raised the stakes in geopolitics. It has also laid bare deeply dysfunctional relations within and between countries, as well

as the state of governance worldwide. The common response to the virus has been containment and control. This is likely to be an apt description for how many governments behave more broadly in 2021.

Image: Pool/Getty Images

Mass vaccination is likely to be uneven and unequal, but it does put recovery on the horizon. Yet as restrictions slowly ease, we forecast that pent up grievances, divisions and disputes are liable to erupt. Tides of civil disquent are reasonably foreseeable and tight political control is a likely response in many regions. Nationalism, authoritarianism and populism have resurged in global politics in recent years, and we forecast that this trend will persist if not intensify in 2021. Self-interest and unilateral action is liable to be the simpler and prefered mode of action.

Economic, social and political crises on such a wide scale could hasten major changes to the ordering of the international system, heralding a new era of power balancing. For many years in Strategic Outlook we, like many others, have warned that the global order is becoming less multilateral and more anarchic and competitive. The pandemic has shown just how much the capacity for multilateral cooperation between states has eroded when the need for it has never been greater to maintain peace and prosperity.

The risk of interstate disputes and conflicts in 2021 is likely to rise towards levels unseen in decades. Relations between the most powerful actors in the international system are at their lowest ebb since the Cold War. The most significant deterioration and the greatest geopolitical risk is between China and the West, particularly the United States. Relations between Russia and the West are mired in mistrust and hostility. Strategic competition between China and India is rising sharply. Arms control is at a historic low, while defence spending is rising. And rivalries among lower-order powers are festering, with responsible mediation of conflicts as absent as regional meddling is often obvious.

As mass vaccination programmes help countries re-open for business, measures to contain the coronavirus will slowly ease. But vaccines themselves are likely to be as much a source of political rivalry as they are a solution for the most profound global risk the world has experienced in decades. Rather than binding the world together in common cause, the coronavirus crisis has had the inverse effect. Discord and vulnerabilities in a global system of complex interdependencies have been exposed. The world will not be the same as it once was.

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Pandemic fallout

Geopolitical fault lines

In this more adversarial landscape, new geopolitical fault lines are emerging and old ones more liable to flare. War between the US and China is still improbable, as is war with Russia. But intensifying competition between the three, particularly the US and China, is unsettling the global balance and making crises involving second and third tier powers more likely.

Frozen conflicts, contested territories, and regions deep in crisis are where power struggles are most likely to play out in terms of military action. Nagorno-Karabakh, Donbass, Kashmir, Ladakh, Western-Sahara, The Sea of Azov, and the Taiwan Strait are just some of the flashpoint regions to watch in 2021. All have the potential to draw in outside competing powers.

At the same time, the erosion of the rules-based multilateral order will continue to make efforts to fight the pandemic less effective than it could be. But it carries deeper geopolitical risks. The Trump administration’s wavering commitment to security guarantees, alliances, trade agreements, international rules and democratic governance, has left smaller countries feeling vulnerable and isolated at a time when they need external support to recover from the pandemic. In some cases this is prompting positive action by such countries to respond to this, notably with greater unity and cooperation between European Union member states.

Reversing this trend of fragmentation on a global level may be impossible. As the US has retrenched and the credibility of its deterrence waned, adherence to the rules in international relations has declined. Bilateralism and unilateralism are the inevitable successors to multilateralism; both favour more powerful self-interested actors and both surged in 2020. This makes global risks – like conflicts, pandemics, migration, proliferation and climate change – much harder to manage. In the meantime, the options smaller states have for financial aid in a post-pandemic world are limited and China is well placed to extend its influence in almost every region.

Image: Antonio Masiello/Getty Images

China’s grand strategy

Understanding China’s grand strategy as well as its tactics is key to understanding geopolitical risk in 2021 and beyond. Simply put, China’s goal is to become a high-tech global superpower that is self-sufficient in its manufacturing capability, and is also able to preserve its territorial integrity while ‘re-unifying’ its claimed territory. The latter requires acquiescence. The former requires assured control of global supply chains and markets to ensure growth, future dominance, and innovation-driven development. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 policy is emblematic of its goals and the centrality of self-sufficient technology manufacturing in its strategy.

The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s signature policy that furthers this strategy through infrastructure investment and development across Asia. The BRI enables Beijing to project greater economic and political power and influence by ultimately transforming beneficiary states in its path into dependent clients. China has also created a parallel and alternative system of international institutions and treaties to those led by the US, such as the Shanghai Pact. These are vehicles for Beijing to advocate the superiority of its own brand of autocratic governance, secure its influence and posture China as an alternative global leader.

For Washington’s policy makers, China’s strategy represents an existential threat to America's global standing. The competition over industry, trade, the security of supply chains, and access to markets and commodities are critical for long-term economic growth and security for both sides. The competition is likely to become more adversarial in 2021, even with a new administration. For China, it is a zero-sum game for dominance played out through a mixture of investment, coercion, co-option and control, often prosecuted through cyber action to gain advantage. For the states in its path, refusal

to at least partially bend to China’s will is rarely

an option.

Reasserting leadership

The Biden administration has pledged to rebuild relationships and US standing. But it is unlikely to recover much lost ground and trust in 2021, and it will struggle to counter China’s political advance. Reasserting US commitments to multilateralism, not least the World Health Organisation and the Paris Climate Accords, are very likely early on. But this is unlikely to substantially restore the effectiveness of supra-national institutions in regulating state behaviour.

The most urgent problems Mr Biden faces are complex and require concerted diplomacy and robust action. His first orders of international business include responding to the Russian hack of SolarWinds, curbing the Iranian nuclear programme, and countering and containing an increasingly assertive and ambitious China. The new president’s ability to count on others and succeed in these policy areas will be limited.

Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The frontlines of competition

The Indo-Pacific region is likely to be where the consequences of Sino-American rivalry are greatest. It is there where China has become more confrontational, coercive and controlling, and confident in being so. We forecast a raft of tensions and crisis points on China’s periphery, from Central Asia, along the Himalayas to the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea.

Beijing appears more intent on pursuing territorial claims that we have seen in years, and using ‘hybrid warfare’ methods to create crises and a sense of international urgency to matters on its agenda. A trade spat with Australia in late 2020 is one of the more overt glimpses of how robust Beijing is becoming in initially trivial disputes, and how willing it is to single out countries and test the strength of their alliances.

It is in this context that the US-China rivalry is the top geopolitical risk in 2021. Unlike the US, China has yet to militarily intervene abroad to safeguard its interests. This is probably just a matter of time as its economic surface area grows and renders it ever more exposed to threats. But its fast evolving military capabilities point to a growing will to exercise hard power in theatres where it has a long-term interest in deterring those that might seek to resist its ambitions.

The Trump administration’s ambivalence to shoring up traditional alliances and promoting democracy among smaller states was at odds with confronting China’s grand strategy. But like its predecessor, the Biden administration will probably see India as its key economic partner to counter China economically in Asia. This adds a new and uncertain dynamic to regional competition in Asia, as well as to conflicts and disputes in which all are stakeholders, such as in Afghanistan and the contested regions on India’s northern borders.

It is not only in the Indo-Pacific where geopolitical risks are rising. US retrenchment from the Middle East has accelerated a trend of instability and rebalancing in a region where it has traditionally underwritten deterrence and meditation. Beyond the persisting tensions between Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel, new dynamics threaten to keep the wider region in a state of strategic overload. A potential Saudi Arabia-UAE-Israel axis on one hand and Turkey-Qatar axis on the other is important to watch as a dynamic that puts weaker states in

their orbit into more uncertain positions over a growing divide.

This new dynamic makes any US attempt to draw Iran back into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action to curb its nuclear ambitions less likely to succeed. But it also makes Mr Biden’s ability to help stabilise the region even harder. Competing powers in the region have already played a hand in conflicts from Libya to Nagorno-Karabakh to Syria. Iran and Saudi Arabia, as the two most hostile powers in the region, are at growing risk of open confrontation as new technologies increasingly enable their proxies to carry out actions that risk drawing them into direct conflict and crisis.

Turkey and Saudi Arabia in particular are two states to monitor as they reposition themselves as dominant players, challenging the status quo and perpetuating disputes in neighbouring countries for economic and geopolitical gains. Their ambitions and behaviours are increasingly in tension with their traditional alliances with the West. This is yielding yet more uncertainty and complexity over how future security, democracy and stability in the wider region is deliverable any time in the future.

Image: AFP Contributor/Getty Images

Image: Tauseef Mustafa/Getty Images

The non-kinetic battlefields

For many global businesses and other organisations, the risks arising from this burgeoning first and second-order power competition are not only limited to unstable regions or the traditional domains of geopolitics. The front lines permeate the global economy, trade, supply chains, markets, workforces, our collective ideas, and indeed the very fabric of our societies. Cyberspace is the principal battlefield where, unlike the conventional physical space, deterrence and the rules of engagement remain poorly defined. If the international system is becoming more anarchic, the cyber system is far more so and has growing potential to yield real-world crises that affect daily lives and stability.

Businesses themselves are on this non-kinetic front line as vectors and targets, a warning we made in Strategic Outlook 2020: The New Political Risks and reiterate again. In the struggle for geopolitical dominance where the stakes of open confrontation are high, every actor is a pawn in the struggle for control of information and its integrity, of revenues, of supply, and of influence in public discourse. Businesses should not underestimate the urgency of the threat and the role they play as actors in this strategic and divided landscape.

Hostile state activity targeting businesses is already surging, and we anticipate this to continue worldwide and take new forms in 2021. China’s strategy of accelerated growth and technological autarky requires the acquisition of trade secrets

and intellectual property, obtained by espionage, regulatory compliance in its jurisdiction, or simple acquisition of companies. It also requires control

of political narratives, which can be obtained by

the same means or simply by coercion as is now

its wont. Global corporations are not exempt

and should anticipate pressure from all sides to

take sides.

Such efforts by Beijing – and indeed other actors such as Russia – to further their ambitions and maintain control at home and abroad are global in scope. From a corporate standpoint they demand greater integration between risk management functions at the highest levels of corporate governance for any organisation wishing to trade in jurisdictions that span geopolitical rivalries. They also require risk management from the core to the periphery, from head office to the vulnerable underbellies in the global supply chain. Africa is likely to be one such arena where cyber security gaps are potentially significant in attempts to harm Western economic interests for strategic gain.

Image: Bill Wechter/Getty Images

A post-pandemic world

The pandemic has been remarkable insofar as lockdowns and restrictions have created a sense of hibernation and stasis. But in our analysis, it is merely a pregnant quiet. Every country in the world has been rendered economically and politically vulnerable, as has nearly every global business. The potential for regeneration and positive change is immense, but so too is the potential for change wrought by those that wish to bring about new realities that better serve narrow self-interests.

Economic and political liberalism in particular are in peril of losing ground. Both rely on a trinity of trust, common rules and cooperation to yield their promised dividends of peace and security. In the profoundly unstable world the pandemic has created but is yet to be fully revealed, these virtues may not hold much currency. Global security and stability in 2021 will therefore probably depend more on containment and control of all risks until a new semblance of order solidifies. This is not a liberal outlook, but a realist one. Knowing how to navigate such a regressive world, or even prevent it, requires imagining this future and considering strategic warnings such as this sooner rather

than later.