CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Consistent

Image: Michele Cattani/Getty Images

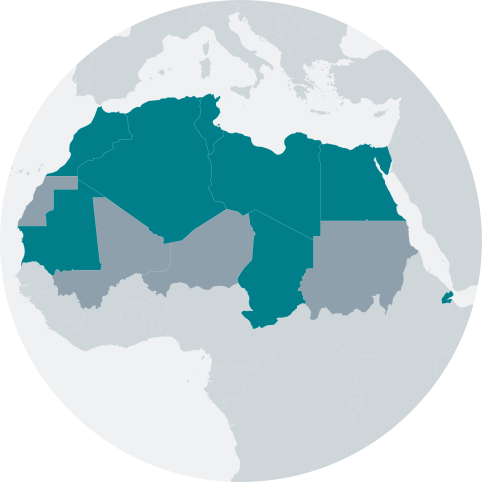

Stability in jeopardy

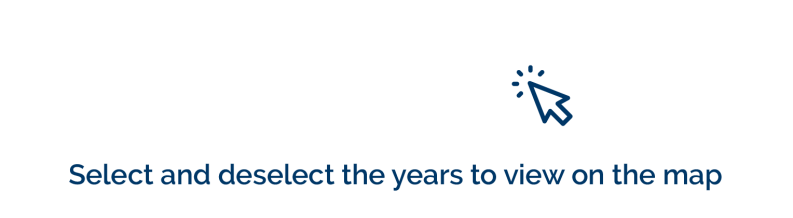

Both Mali and Sudan will arrive at critical junctures for their longer-term stability next year. The two will probably experience domestic friction over the role of the military in politics, after coups in 2019 and 2020. Pressure to resolve governance issues from international and regional organisations and donors, ranging from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) towards Mali and the African Union towards Sudan, will probably be high throughout 2021. But there are few signs in either country that the military is willing to hand over power to civilian authorities.

Sudan’s ambitious three-year political transition is particularly vulnerable to collapse in mid-2021. The government has made some progress in achieving key milestones, including in September 2020 when it reached a deal with some rebel groups to solve long-running conflicts in Blue Nile, Darfur and South Kordofan. The military, which heads the governing sovereignty council, is due to hand over the body’s chairmanship to a civilian leader in June. It is unlikely to do so easily, and disagreements on who to appoint will probably spark protests and unrest, including in major cities like Khartoum in 2021.

Beyond this handover, the Sudanese government will probably struggle to address a serious fiscal and economic crisis. The economic outlook is poor: the IMF forecast GDP will grow by 0.8% in 2021, after shrinking by 8.4% in 2020. This, alongside trends of high inflation and unemployment, as well as poor state finances, means the government will be squeezed in its ability to deliver on public demands for better living conditions, and on the peace deal it reached with rebel factions.

The US promise that it will lift Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism – and the associated sanctions – will probably unblock international financing. But we anticipate the economic benefits from this are unlikely to be felt in 2021, with persistent infrastructure and reputational concerns likely to slow a marked return in foreign investment that would spur economic growth. This will probably sustain public dissatisfaction with the government over living conditions, but not push the military away from holding onto power.

Unlike in Sudan, external pressures seem less likely to steer Mali’s political and security risk outlook in 2021. The military junta has shown little willingness to surrender control to a fully civilian and democratic system of government. While regional organisations like ECOWAS will probably try to encourage the military to hand over to a civilian administration, this will probably have little effect on the pace of the transition set by the military. We forecast the military will remain largely in power through much of 2021, sustaining a high likelihood of protests, particularly in Bamako. It will also leave unresolved conflicts in the north of the country at risk of escalating.

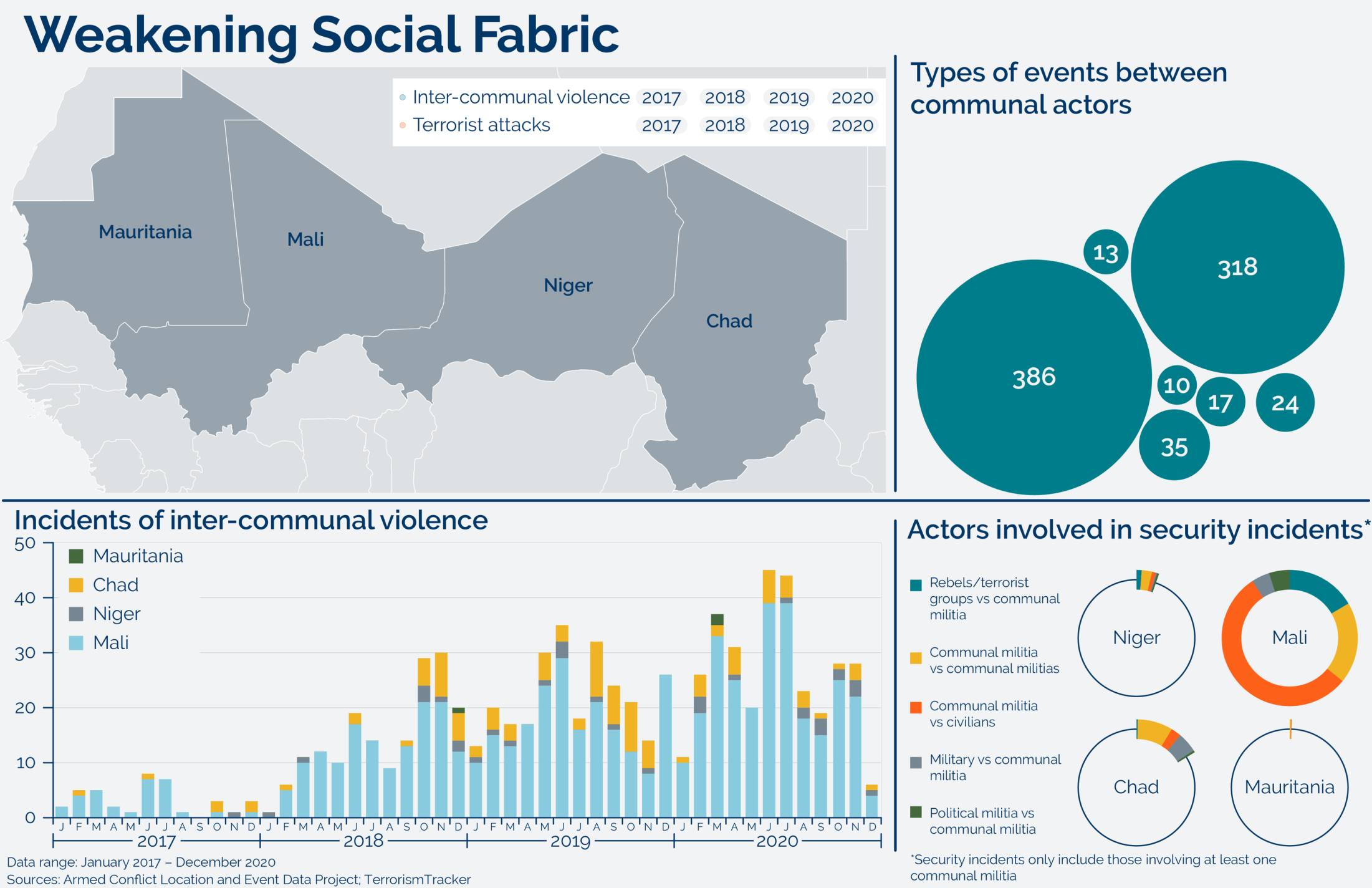

Political instability in Mali will probably perpetuate security risks in the Sahel region in 2021, including terrorism. We doubt that French and UN troop commitments will reduce significantly. But domestic political turmoil will limit the Malian state's ability to reverse trends of insecurity. Competition between Islamic State and Al-Qaeda factions is likely to persist in Mali and Niger, which will probably lead to increased levels of violence along their shared borders. This includes direct fighting between rival militant factions, as well as a higher tempo of attacks against security forces and vulnerable foreign interests across the Sahel.

Libya similarly carries a high potential for deepening insecurity and conflict spillover affecting its neighbours. The long-running conflict between the UN-backed government and the eastern authorities looks likely to draw in even more foreign military, financial or political involvement in 2021. This includes from the UAE, Russia and Turkey, which back different sides of the conflict. Such regional rivalries are likely to prolong the timeline for stability in Libya. We also anticipate infighting among the many Libyan stakeholders to sustain cycles of fighting, disruption to oil production, and protests in major cities throughout 2021.

Elsewhere in the region, Algeria is likely to walk a fine line between stability and serious financial troubles without external assistance. Unlike other Maghreb countries, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has rejected seeking foreign financial assistance. But the government is facing multiple challenges, including slowing growth, a weak fiscal position, and dwindling foreign reserves. The impacts of a prolonged Covid-19 outbreak and relatively low oil prices will accelerate these trends, and the government will probably need to seek external financing in 2021 to avoid an even more serious governance crisis. Tebboune is likely to stay on, if fit and well, but government reshuffles and localised protests and strikes will probably once again be the norm for Algeria next year.

The outlook for Egypt is less bleak, as the country seems to have stabilised its macro-economic indicators and economy in the years since its IMF loan in 2016. Although seemingly stable, simmering discontent over socio-economic conditions will probably prompt some hardship protests in 2021, particularly amid slowing growth and rising unemployment. We do not anticipate this to seriously threaten President Sisi’s position next year, particularly as the government looks likely to maintain a tight grip on dissent and ensure relative security. But we do not anticipate much international pressure on Egypt to shift this approach in 2021.

Algeria is likely to walk a fine line between stability and serious financial troubles without external assistance. Unlike other Maghreb countries, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has rejected seeking foreign financial assistance.

Image: David Degner/Getty Images

Image: Souleymane Ag Anara/Getty Images

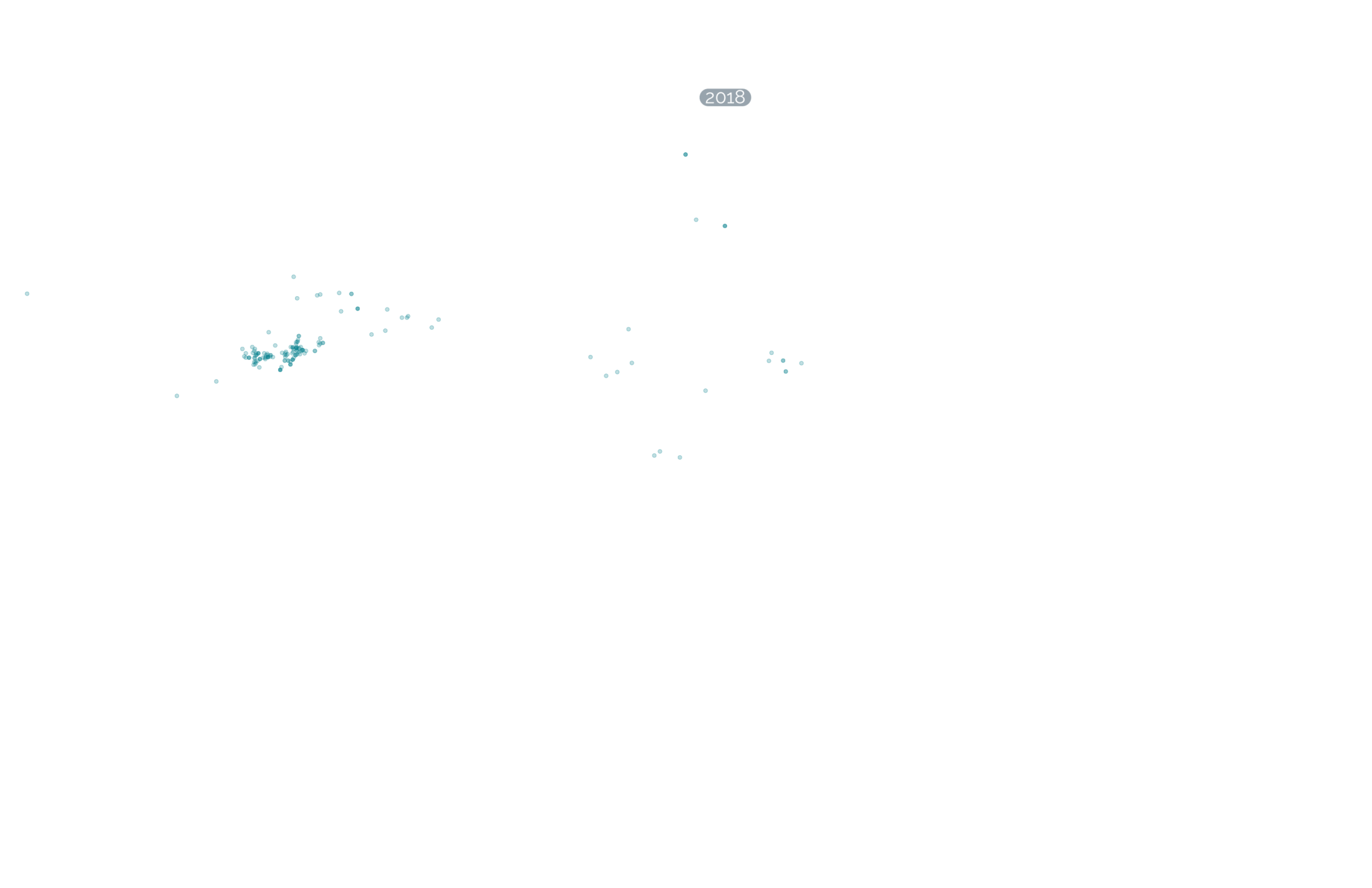

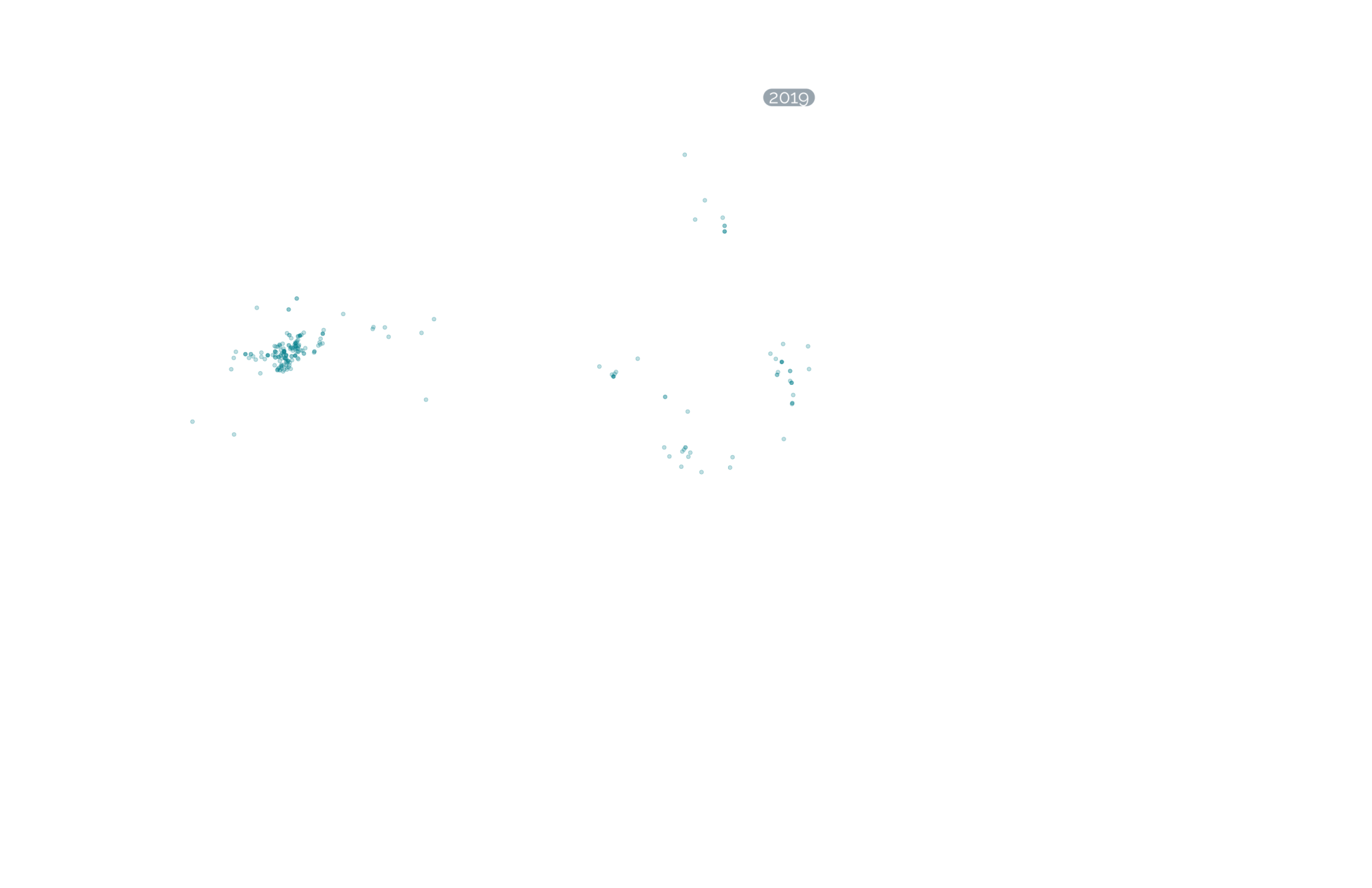

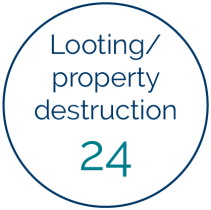

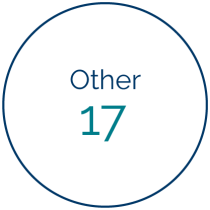

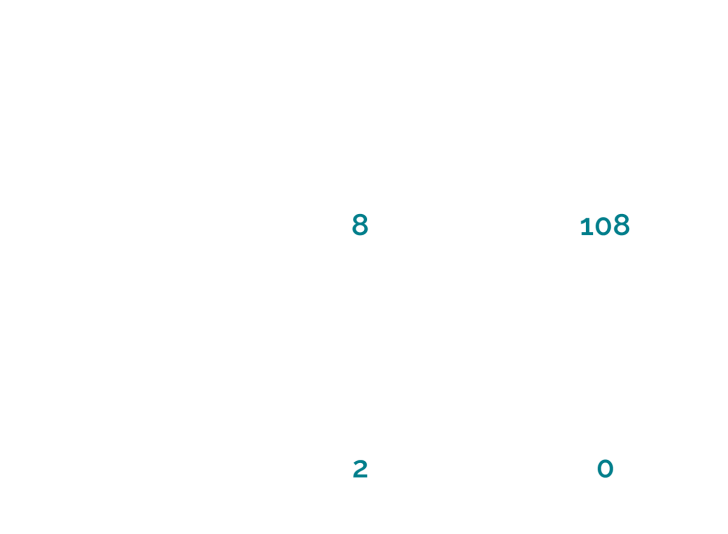

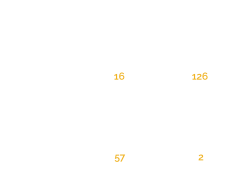

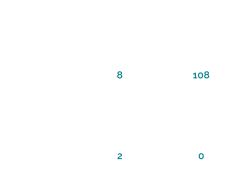

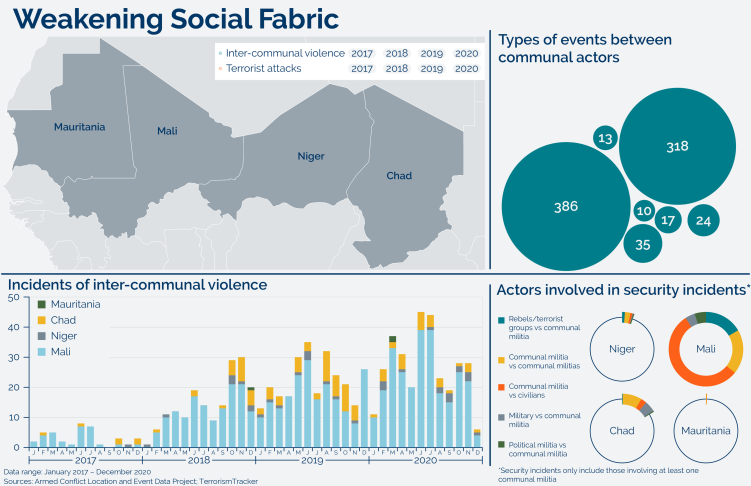

Sources: The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); Risk Advisory TerrorismTracker

Forecasts

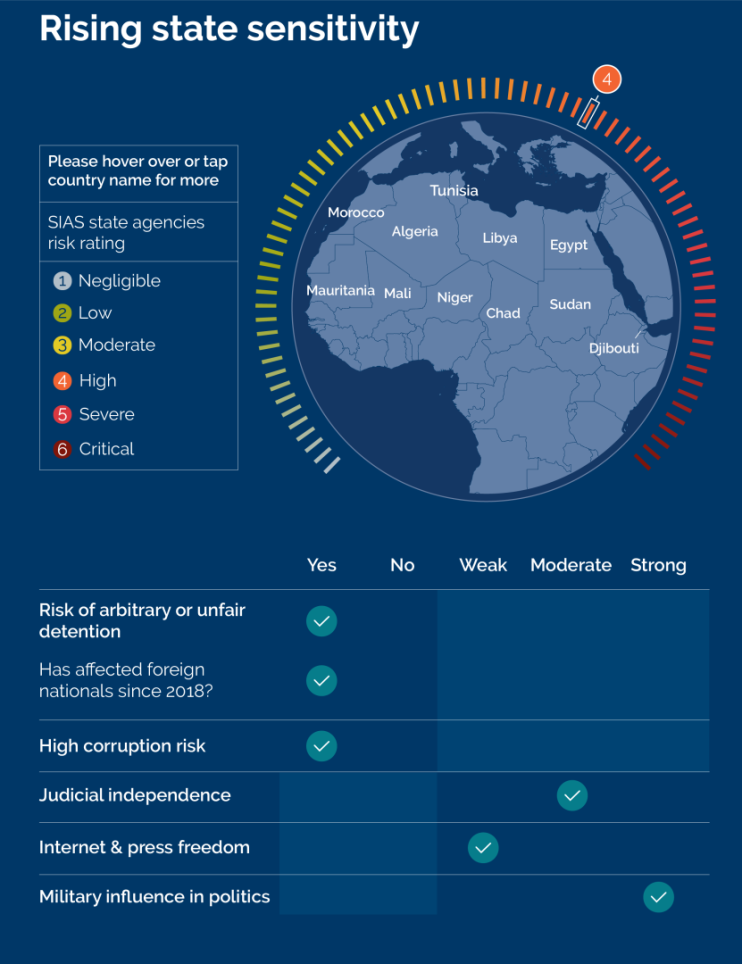

The ongoing consolidation of power means that President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani will probably sustain difficulties of doing business for foreign firms in Mauritania in 2021. This includes navigating changing patronage networks. The president consolidated his control over the various security branches in 2020, and seems to be settling into his post. But in an attempt to appease the political opposition and break with his predecessor, further corruption cases and allegations around the former president and his networks are likely in 2021.

Business risks in Mauritania

State suppression of dissent is likely to be high around various elections in the region in 2021. Presidential polls are due in Chad and Djibouti in April; neither of the two long-sitting presidents have said they will run, although both probably will. In Niger, a presidential election run-off is likely and due in early 2021. The authorities will probably try limiting the ability of opposition groups to organise politically around the polls and hold protests. This includes through cuts to communications channels during election periods, which would carry extra operational risks for foreign businesses and organisations.

Contentious elections

North African countries are likely to make only slow or limited economic recoveries amid the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021. The governments of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, in particular, will probably struggle to reinvigorate their tourism sector, which is an important source of foreign currency and employment. We anticipate rising public discontent in all three and with it more protests. This will probably affect Tunisia the most as a wrangling parliament slows an effective government response.

Tanking tourism

Forecasts

Outliers

Troubled succession in Morocco

Significant political instability in Morocco emerges around an unplanned succession. The 17-year-old crown prince takes over after the king, Mohammed VI, suddenly dies from illness or steps down due to poor health. Prince Moulay Hassan fails to gain public support in this new role. This adds to existing sources of public dissatisfaction and triggers large protests in major cities that are openly anti-monarchy, prompting a protracted governance crisis and longer-term instability.

Monitoring Points

Economic reforms in Sudan

The Sudanese government implementing cuts to state spending in 2021 to improve its fiscal position would signal increased protests and associated unrest, including in major cities like Port Sudan and Khartoum. Cuts to fuel subsidies, as well as reductions of state support on medicines, bread and key services like electricity, are all potentially on the cards in 2021. This is particularly if the Sudanese government takes on international assistance from financial institutions, after US sanctions are lifted as a result of Sudan being removed as a state sponsor of terrorism.

Climate crisis

Unusually severe climate events like heavy rains and extended and widespread droughts in the Sahel are a growing security risk due to the climate crisis. This is a key development to watch out for in 2021. Damaged infrastructure and crops in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Niger and Sudan can deepen hardship and drive up localised conflicts over resources. Severe weather events and the inability of governments to handle their effects are also triggers for localised protests and associated unrest in 2021.

Deadly attacks in Egypt

A marked increase in the frequency and deadliness of terrorist attacks in major cities in mainland Egypt, including Alexandria and Cairo, would trigger a weakening of public support for the authorities. Ensuring security has been a key source of domestic legitimacy for the president. Counter-terrorism operations by the Egyptian security forces appear to have been effective in mostly containing the terrorism threat to North Sinai in 2019. But a reversal of this trend, in combination with several other factors such as an intensified crackdown on dissent and a dip in living conditions, would mean that Egypt’s stability trajectory would worsen.

Images: Aurelien Meunier; Eduardo Soteras; Ryad Kramdi; Alexis Huguet; Gianluigi Guercia; Michele Cattani/Getty Images

Overall trend: Consistent

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Image: Michele Cattani/Getty Images

Stability in jeopardy

Both Mali and Sudan will arrive at critical junctures for their longer-term stability next year. The two will probably experience domestic friction over the role of the military in politics, after coups in 2019 and 2020. Pressure to resolve governance issues from international and regional organisations and donors, ranging from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) towards Mali and the African Union towards Sudan, will probably be high throughout 2021. But there are few signs in either country that the military is willing to hand over power to civilian authorities.

Sudan’s ambitious three-year political transition is particularly vulnerable to collapse in mid-2021. The government has made some progress in achieving key milestones, including in September 2020 when it reached a deal with some rebel groups to solve long-running conflicts in Blue Nile, Darfur and South Kordofan. The military, which heads the governing sovereignty council, is due to hand over the body’s chairmanship to a civilian leader in June. It is unlikely to do so easily, and disagreements on who to appoint will probably spark protests and unrest, including in major cities like Khartoum

in 2021.

Beyond this handover, the Sudanese government will probably struggle to address a serious fiscal and economic crisis. The economic outlook is poor: the IMF forecast GDP will grow by 0.8% in 2021, after shrinking by 8.4% in 2020. This, alongside trends of high inflation and unemployment, as well as poor state finances, means the government will be squeezed in its ability to deliver on public demands for better living conditions, and on the peace deal it reached with rebel factions.

The US promise that it will lift Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism – and the associated sanctions – will probably unblock international financing. But we anticipate the economic benefits from this are unlikely to be felt in 2021, with persistent infrastructure and reputational concerns likely to slow a marked return in foreign investment that would spur economic growth. This will probably sustain public dissatisfaction with the government over living conditions, but not push the military away from holding onto power.

Unlike in Sudan, external pressures seem less likely to steer Mali’s political and security risk outlook in 2021. The military junta has shown little willingness to surrender control to a fully civilian and democratic system of government. While regional organisations like ECOWAS will probably try to encourage the military to hand over to a civilian administration, this will probably have little effect on the pace of the transition set by the military. We forecast the military will remain largely in power through much of 2021, sustaining a high likelihood of protests, particularly in Bamako. It will also leave unresolved conflicts in the north of the country at risk of escalating.

Political instability in Mali will probably perpetuate security risks in the Sahel region in 2021, including terrorism. We doubt that French and UN troop commitments will reduce significantly. But domestic political turmoil will limit the Malian state's ability to reverse trends of insecurity. Competition between Islamic State and Al-Qaeda factions is likely to persist in Mali and Niger, which will probably lead to increased levels of violence along their shared borders. This includes direct fighting between rival militant factions, as well as a higher tempo of attacks against security forces and vulnerable foreign interests across the Sahel.

Libya similarly carries a high potential for deepening insecurity and conflict spillover affecting its neighbours. The long-running conflict between the UN-backed government and the eastern authorities looks likely to draw in even more foreign military, financial or political involvement in 2021. This includes from the UAE, Russia and Turkey, which back different sides of the conflict. Such regional rivalries are likely to prolong the timeline for stability in Libya. We also anticipate infighting among the many Libyan stakeholders to sustain cycles of fighting, disruption to oil production, and protests in major cities throughout 2021.

Elsewhere in the region, Algeria is likely to walk a fine line between stability and serious financial troubles without external assistance. Unlike other Maghreb countries, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has rejected seeking foreign financial assistance. But the government is facing multiple challenges, including slowing growth, a weak fiscal position, and dwindling foreign reserves. The impacts of a prolonged Covid-19 outbreak and relatively low oil prices will accelerate these trends, and the government will probably need to seek external financing in 2021 to avoid an even more serious governance crisis. Tebboune is likely to stay on, if fit and well, but government reshuffles and localised protests and strikes will probably once again be the norm for Algeria next year.

The outlook for Egypt is less bleak, as the country seems to have stabilised its macro-economic indicators and economy in the years since its IMF loan in 2016. Although seemingly stable, simmering discontent over socio-economic conditions will probably prompt some hardship protests in 2021, particularly amid slowing growth and rising unemployment. We do not anticipate this to seriously threaten President Sisi’s position next year, particularly as the government looks likely to maintain a tight grip on dissent and ensure relative security. But we do not anticipate much international pressure on Egypt to shift this approach in 2021.

Image: David Degner/Getty Images

Algeria is likely to walk a fine line between stability and serious financial troubles without external assistance. Unlike other Maghreb countries, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has rejected seeking foreign financial assistance.

Image: Souleymane Ag Anara/Getty Images

Sources: The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); Risk Advisory TerrorismTracker

Forecasts

North African countries are likely to make only slow or limited economic recoveries amid the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021. The governments of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, in particular, will probably struggle to reinvigorate their tourism sector, which is an important source of foreign currency and employment. We anticipate rising public discontent in all three and with it more protests. This will probably affect Tunisia the most as a wrangling parliament slows an effective government response.

Tanking tourism

The ongoing consolidation of power means that President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani will probably sustain difficulties of doing business for foreign firms in Mauritania in 2021. This includes navigating changing patronage networks. The president consolidated his control over the various security branches in 2020, and seems to be settling into his post. But in an attempt to appease the political opposition and break with his predecessor, further corruption cases and allegations around the former president and his networks are likely in 2021.

Business risks in Mauritania

State suppression of dissent is likely to be high around various elections in the region in 2021. Presidential polls are due in Chad and Djibouti in April; neither of the two long-sitting presidents have said they will run, although both probably will. In Niger, a presidential election run-off is likely and due in early 2021. The authorities will probably try limiting the ability of opposition groups to organise politically around the polls and hold protests. This includes through cuts to communications channels during election periods, which would carry extra operational risks for foreign businesses and organisations.

Contentious elections

Outliers

Troubled succession in Morocco

Significant political instability in Morocco emerges around an unplanned succession. The 17-year-old crown prince takes over after the king, Mohammed VI, suddenly dies from illness or steps down due to poor health. Prince Moulay Hassan fails to gain public support in this new role. This adds to existing sources of public dissatisfaction and triggers large protests in major cities that are openly anti-monarchy, prompting a protracted governance crisis and longer-term instability.

Monitoring Points

Economic reforms in Sudan

Climate crisis

The Sudanese government implementing cuts to state spending in 2021 to improve its fiscal position would signal increased protests and associated unrest, including in major cities like Port Sudan and Khartoum. Cuts to fuel subsidies, as well as reductions of state support on medicines, bread and key services like electricity, are all potentially on the cards in 2021. This is particularly if the Sudanese government takes on international assistance from financial institutions, after US sanctions are lifted as a result of Sudan being removed as a state sponsor of terrorism.

Deadly attacks in Egypt

A marked increase in the frequency and deadliness of terrorist attacks in major cities in mainland Egypt, including Alexandria and Cairo, would trigger a weakening of public support for the authorities. Ensuring security has been a key source of domestic legitimacy for the president. Counter-terrorism operations by the Egyptian security forces appear to have been effective in mostly containing the terrorism threat to North Sinai in 2019. But a reversal of this trend, in combination with several other factors such as an intensified crackdown on dissent and a dip in living conditions, would mean that Egypt’s stability trajectory would worsen.

Unusually severe climate events like heavy rains and extended and widespread droughts in the Sahel are a growing security risk due to the climate crisis. This is a key development to watch out for in 2021. Damaged infrastructure and crops in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Niger and Sudan can deepen hardship and drive up localised conflicts over resources. Severe weather events and the inability of governments to handle their effects are also triggers for localised protests and associated unrest in 2021.

Images: Aurelien Meunier; Eduardo Soteras; Ryad Kramdi; Alexis Huguet; Gianluigi Guercia; Michele Cattani/Getty Images