CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Worsening

Image: Yawar Nazir/Getty Images

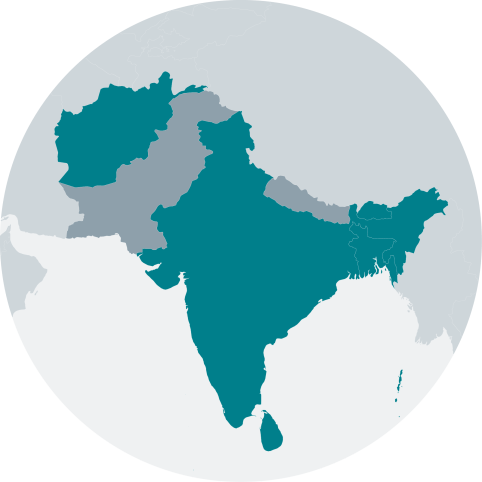

As the economic and humanitarian tolls of Covid-19 in South Asia converge in 2021, public discontent is likely to rise regionwide. The World Bank forecasts regional growth contracting by 7.7%, with the Indian economy forecast to shrink by 10%. Unemployment will almost certainly rise and remittances fall across the region in 2021. The governments of Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka will be challenged by this but are unlikely to feel threatened by any civil disquiet. Afghanistan, the Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan, however, are more vulnerable to instability.

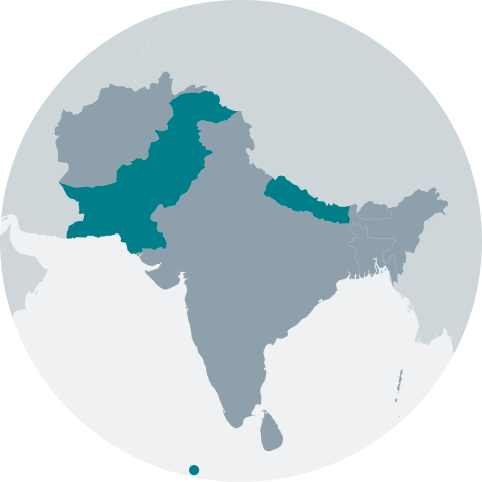

Against this unsettled backdrop, the most dangerous strategic security risk in the region in 2021 is a mismanaged conflict escalating between India and Pakistan. The potential for a terrorist or military incident in the disputed region of Kashmir that quickly leads to a military standoff will remain high throughout 2021. A crisis triggered by a terrorist attack on an Indian military convoy in 2019 brought both countries close to war and resulted in the closure of strategic air corridors and significant disruption. Attacks have become more frequent in Kashmir and we forecast this will almost certainly continue.

The persistent likelihood of a crisis is tied to several converging factors. Foremost among them is the robust nationalist stances of the governments in New Delhi and Islamabad, with unilateral changes to the political status of the contested Kashmir region. India’s move to bring Jammu and Kashmir under the full control of the central government and Pakistan's provisional declaration of Gilgit-Baltistan in Kashmir as the country’s fifth province in 2020, are provocative, risky and unprecedented moves. Not only do they change the nature of the dispute but they tie any negative developments in the region more closely to central government policy and sovereignty. Making avenues for de-escalation narrower than they already are.

The period of greatest risk is probably the first half of the year. In April and May, India will hold elections in four states. The outcome of these is unlikely to prompt a change in the governing BJP party's stance towards Kashmir. But if the poll forecasts look gloomy to the governing party, the Modi government may see an opportunity to reverse that with further moves over the region. These would play to its Hindu-nationalist base and potentially lead it to confront Pakistan with no peaceably achievable endgame.

The Pakistani government is in a worse position. Its prime minister, Imran Khan, faces a protest campaign to oust him that is likely to run through early 2021. It will probably fail. Mr Khan, who relies on the support of the military, seems intent on playing nationalist cards to maintain his position and recover support for his Tehreek-e-Insaf party amid a serious economic decline in the country. Provisionally declaring Gilgit-Baltistan as a fifth province and holding elections there are bold moves in that vein, and provide the BJP with a reason to be even more hardline in the dispute.

All of this makes the risk of India and Pakistan misreading each other’s intentions in the event of a military or, more likely, a terrorist incident all the greater. Added to this mix are other geopolitical forces that threaten to increase pressure to the brittle situation on India’s northern borders. China’s increasingly forward military deployments in the disputed Ladakh region with India, and India’s continued building of infrastructure in the region, were provocative moves by both sides which unsettled a long-established status quo and led to clashes and the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers.

That incident was quickly de-escalated but it destabilised another strategic faultline on India's northern borders. It raised tensions between the two great powers of the region and brought to the fore the changing and fraught nature of their relations. Indeed, a key feature that is likely to mark 2021 is souring relations between India and China, as they increasingly view each other as strategic competitors jostling for influence and access to markets and supply chains across the region. Even if India and China resume cordial ties this year, which New Delhi seems to want, economic competition between them will impact how other states behave, making cordiality seem more like a cover than progress towards a regional balance.

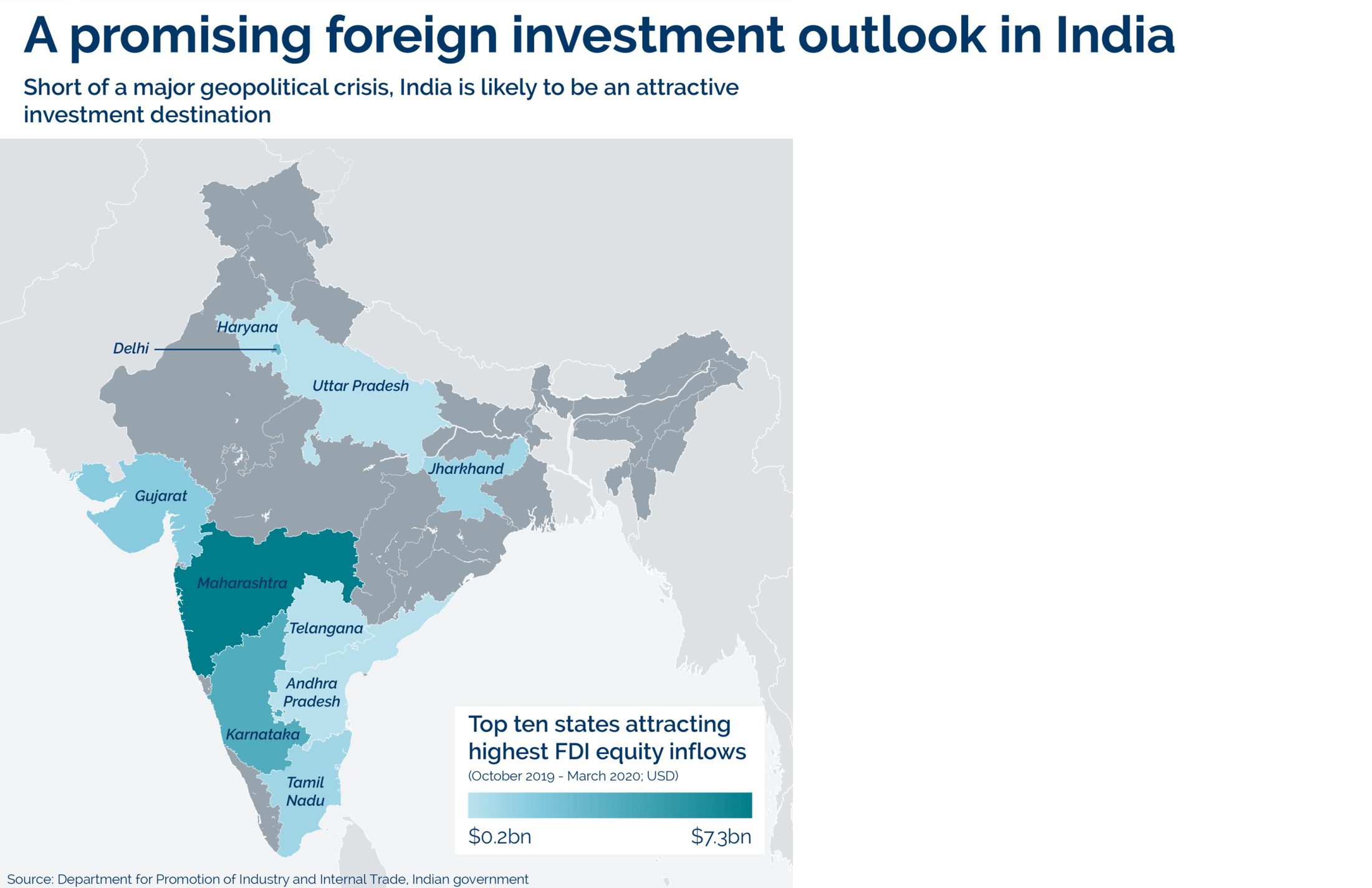

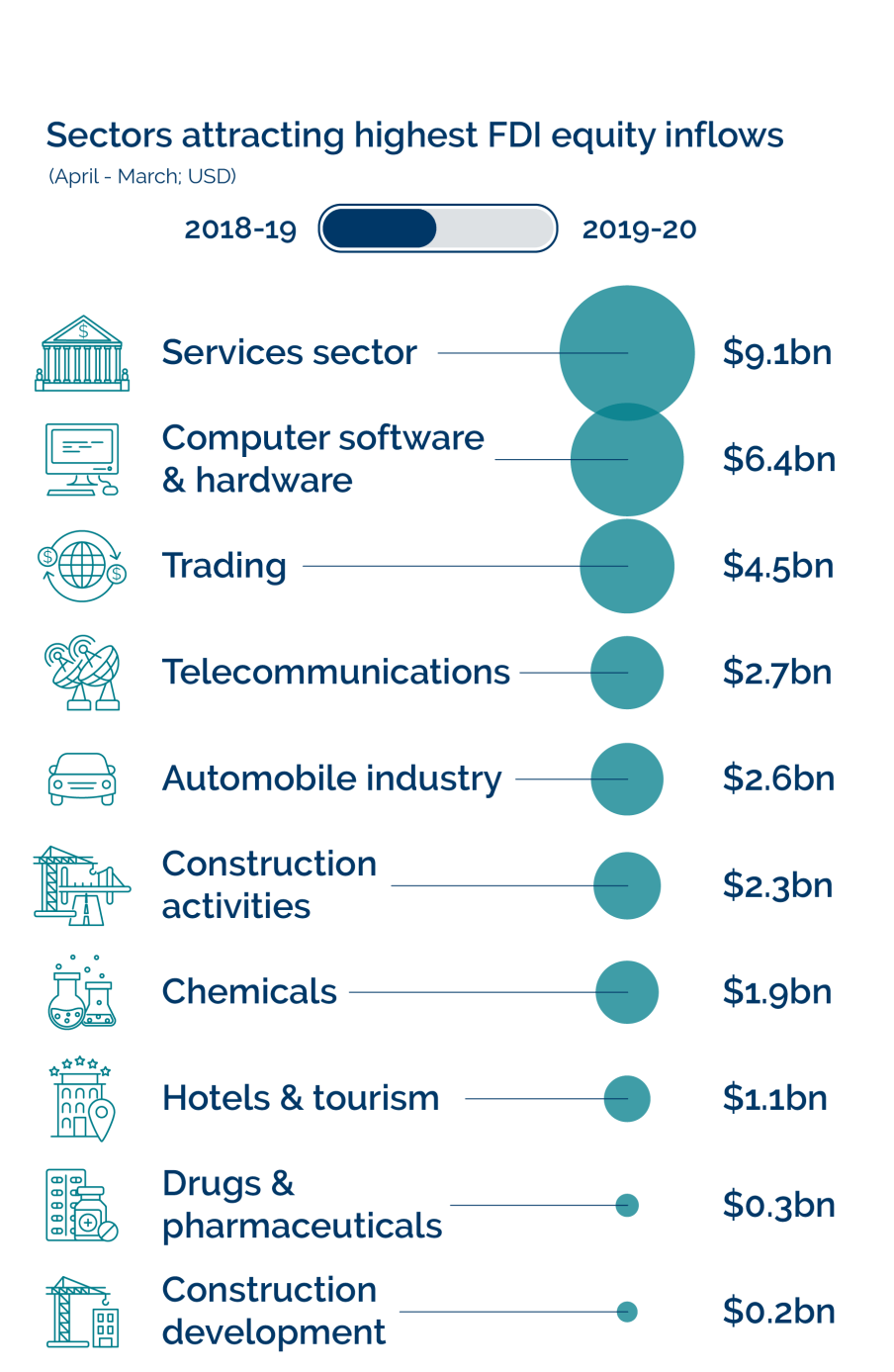

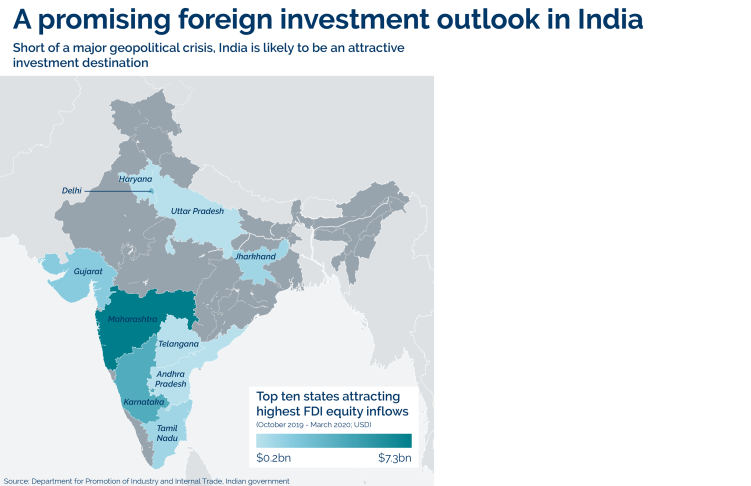

This rivalry is most likely to play out economically. India will probably look to curb Chinese investment in 2021, while using its investing power to compete with Beijing for influence in neighbouring states hard hit by the pandemic. Some South Asian governments may find they need to abandon or deviate from their balancing acts with New Delhi and Beijing, and lean towards one or the other. We anticipate that Nepal and Sri Lanka will favour Chinese investment in 2021, with the Maldives swinging towards India.

India will probably also pursue more protectionist measures that disproportionately impact the access of Chinese goods into Indian markets. This is likely to become a key source of dispute with Beijing. But more targeted actions like Indian bans on Chinese apps and technology are unlikely without a flare-up in military tensions between the two. Another driver for tensions is India forming a closer alliance with the United States to counter China’s rise with their ‘Quad partners’, Australia and Japan. This could cause or be prompted by another military flare-up in the Ladakh region as China seeks to apply coercive pressure on India.

Such a crisis in Ladakh could present Pakistan with a high-stakes opportunity to apply pressure on India in Kashmir and require it to stretch its forces. A coordinated move by China and Pakistan on India over its northern disputed territories is an unlikely and dangerous escalation. But simultaneous crises in both territories involving three nuclear powers would be immensely destabilising, and is a scenario to be alert to should Sino-Indian relations deteriorate.

There are factors that weigh against this worst-case scenario. Foremost among them is a new administration in the US that is more likely to play an active and constructive mediating role in any disputes than its predecessor. There are also common interests in regional stability shared by India and China particularly, not least in Afghanistan where both are heavily invested.

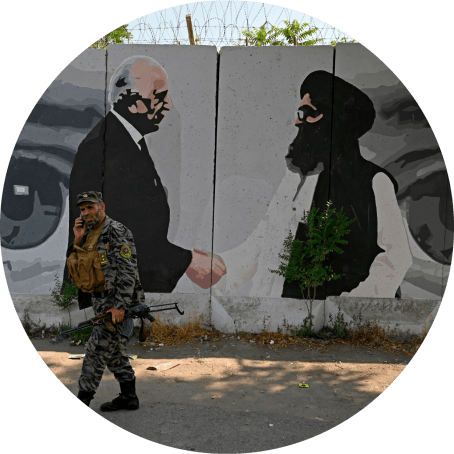

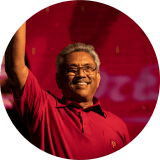

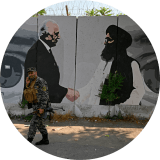

We forecast that the Biden administration will stick to pre-existing plans to draw down US forces from Afghanistan by May. This will lay bare the intentions of the players on the ground and regional stakeholders. Peace talks are likely to fail yet again unless they secure for the Taliban effective control over key cities and positions in key ministries. The timeline of US withdrawal aligns with the fighting season in Afghanistan, and if a deal is not secured and US forces leave, we would expect a Taliban offensive to seize those cities.

In any event, negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban are unlikely to bring an end to the conflict in 2021. We anticipate that Afghanistan will continue to welcome economic aid from both India and China over the coming years. In this arena, India and China share common interests in the stability of the country, although neither appears prepared to militarily intervene to protect their interests if the US does indeed withdraw. If nothing else, this would show that, as regional powers struggle for dominance in South Asia, there is little prospect of one emerging as a leader to underwrite wider stability.

A key feature that is likely to mark 2021 is souring relations between India and China, as they increasingly view each other as strategic competitors jostling for influence and access to markets and supply chains across the region.

We forecast that the Biden administration will stick to pre-existing plans to draw down US forces from Afghanistan by May. This will lay bare the intentions of the players on the ground and regional stakeholders.

Image: Narinder Nanu/Getty Images

Image: Manjunath Kiran/Getty Images

Forecasts

Protests over a controversial citizenship law are likely to re-emerge in Assam and West Bengal ahead of state polls there in April-May 2021. But like in 2020, the governing BJP is highly unlikely to stop the implementation of the legislation, which grants citizenship to non-Muslim migrants, under specific criteria. Any protests would be unlikely to spread to other parts of India and impact major cities.

Citizenship law protests in India

More frequent separatist attacks are likely in Balochistan and Karachi in 2021. An assault on the stock exchange in the city in June 2020 showed the determination of separatists to target hardened high-profile targets. We assess that such a major attack on a Chinese-funded project or interests in southern Pakistan is a likely scenario in 2021, particularly construction and extractives targets that they perceive exploit local land and resources.

Separatists intensify attacks in Pakistan

larger word size, whereas those less commonly used are shown smaller.

to think about Covid-19

Despite a legal challenge, early elections will probably go ahead in April-May after the governing NCP party split in December 2020. We assess that several thousands of people will attend protests ahead of the elections, mainly in Kathmandu. We also forecast that no single party will win an outright majority, meaning a resulting governing coalition is likely to face persistent instability in 2021.

Early elections in Nepal

Forecasts

Outliers

The assassination of the Afghan president

Monitoring Points

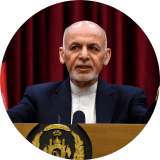

Consolidating power in Sri Lanka

The extent to which President Gotabaya Rajapaksa pushes loyalists into key decision-making posts will indicate a how strong a swing he makes towards China in attracting investment. A constitutional amendment in late 2020 gave the president greater powers to hire and fire the prime minister and judges as well as set up commissions. It would also indicate a leaning towards a more authoritarian style of government. Good relations between him and the prime minister, who is also his brother, will ensure relative political stability in 2021.

State elections in India

State elections in 2021 will be the first clear measure of how well the government is handling the Covid-19 outbreak in the public mind. Even if the governing BJP does not win any new states in the elections due in April-May, an increase in vote shares would signal that the pandemic, high unemployment and poor economic conditions have not hampered the party’s popularity or its agenda. In the unlikely scenario that the BJP loses all state elections in April-May, we would anticipate a slowing of reforms to incentivise investment. But such a result would make protests by farmers and informal workers less likely.

troop withdrawals in afghanistan

Although we forecast that peace talks will probably fail, or at least not conclude in 2021, several developments may signal more positive progress. These include the Taliban agreeing to a minimum ceasefire period that suspends assaults on provincial centres. Notices of any delay to the planned US withdrawal would also signal a likely and imminent escalation in attacks in cities.

Images: Wakil Kohsar; Carl Court; Ishara S. Kodikara; Paula Bronstein; Wakil Kohsar; Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Overall trend: Worsening

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Image: Yawar Nazir/Getty Images

As the economic and humanitarian tolls of Covid-19 in South Asia converge in 2021, public discontent is likely to rise regionwide. The World Bank forecasts regional growth contracting by 7.7%, with the Indian economy forecast to shrink by 10%. Unemployment will almost certainly rise and remittances fall across the region in 2021. The governments of Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka will be challenged by this but are unlikely to feel threatened by any civil disquiet. Afghanistan, the Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan, however, are more vulnerable to instability.

Against this unsettled backdrop, the most dangerous strategic security risk in the region in 2021 is a mismanaged conflict escalating between India and Pakistan. The potential for a terrorist or military incident in the disputed region of Kashmir that quickly leads to a military standoff will remain high throughout 2021. A crisis triggered by a terrorist attack on an Indian military convoy in 2019 brought both countries close to war and resulted in the closure of strategic air corridors and significant disruption. Attacks have become more frequent in Kashmir and we forecast this will almost

certainly continue.

The persistent likelihood of a crisis is tied to several converging factors. Foremost among them is the robust nationalist stances of the governments in New Delhi and Islamabad, with unilateral changes to the political status of the contested Kashmir region. India’s move to bring Jammu and Kashmir under the full control of the central government and Pakistan's provisional declaration of Gilgit-Baltistan in Kashmir as the country’s fifth province in 2020, are provocative, risky and unprecedented moves. Not only do they change the nature of the dispute but they tie any negative developments in the region more closely to central government policy and sovereignty. Making avenues for de-escalation narrower than they already are.

The period of greatest risk is probably the first half of the year. In April and May, India will hold elections in four states. The outcome of these is unlikely to prompt a change in the governing BJP party's stance towards Kashmir. But if the poll forecasts look gloomy to the governing party, the Modi government may see an opportunity to reverse that with further moves over the region. These would play to its Hindu-nationalist base and potentially lead it to confront Pakistan with no peaceably achievable endgame.

The Pakistani government is in a worse position. Its prime minister, Imran Khan, faces a protest campaign to oust him that is likely to run through early 2021. It will probably fail. Mr Khan, who relies on the support of the military, seems intent on playing nationalist cards to maintain his position and recover support for his Tehreek-e-Insaf party amid a serious economic decline in the country. Provisionally declaring Gilgit-Baltistan as a fifth province and holding elections there are bold moves in that vein, and provide the BJP with a reason to be even more hardline in the dispute.

All of this makes the risk of India and Pakistan misreading each other’s intentions in the event of a military or, more likely, a terrorist incident all the greater. Added to this mix are other geopolitical forces that threaten to increase pressure to the brittle situation on India’s northern borders. China’s increasingly forward military deployments in the disputed Ladakh region with India, and India’s continued building of infrastructure in the region, were provocative moves by both sides which unsettled a long-established status quo and led to clashes and the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers.

That incident was quickly de-escalated but it destabilised another strategic faultline on India's northern borders. It raised tensions between the two great powers of the region and brought to the fore the changing and fraught nature of their relations. Indeed, a key feature that is likely to mark 2021 is souring relations between India and China, as they increasingly view each other as strategic competitors jostling for influence and access to markets and supply chains across the region. Even if India and China resume cordial ties this year, which New Delhi seems to want, economic competition between them will impact how other states behave, making cordiality seem more like a cover than progress towards a regional balance.

This rivalry is most likely to play out economically. India will probably look to curb Chinese investment in 2021, while using its investing power to compete with Beijing for influence in neighbouring states hard hit by the pandemic. Some South Asian governments may find they need to abandon or deviate from their balancing acts with New Delhi and Beijing, and lean towards one or the other. We anticipate that Nepal and Sri Lanka will favour Chinese investment in 2021, with the Maldives swinging towards India.

India will probably also pursue more protectionist measures that disproportionately impact the access of Chinese goods into Indian markets. This is likely to become a key source of dispute with Beijing. But more targeted actions like Indian bans on Chinese apps and technology are unlikely without a flare-up in military tensions between the two. Another driver for tensions is India forming a closer alliance with the United States to counter China’s rise with their ‘Quad partners’, Australia and Japan. This could cause or be prompted by another military flare-up in the Ladakh region as China seeks to apply coercive pressure on India.

Image: Narinder Nanu/Getty Images

Image: Manjunath Kiran/Getty Images

A key feature that is likely to mark 2021 is souring relations between India and China, as they increasingly view each other as strategic competitors jostling for influence and access to markets and supply chains across the region.

Forecasts

Despite a legal challenge, early elections will probably go ahead in April-May after the governing NCP party split in December 2020. We assess that several thousands of people will attend protests ahead of the elections, mainly in Kathmandu. We also forecast that no single party will win an outright majority, meaning a resulting governing coalition is likely to face persistent instability in 2021.

Early elections in Nepal

Protests over a controversial citizenship law are likely to re-emerge in Assam and West Bengal ahead of state polls there in April-May 2021. But like in 2020, the governing BJP is highly unlikely to stop the implementation of the legislation, which grants citizenship to non-Muslim migrants, under specific criteria. Any protests would be unlikely to spread to other parts of India and impact major cities.

Citizenship law protests in India

More frequent separatist attacks are likely in Balochistan and Karachi in 2021. An assault on the stock exchange in the city in June 2020 showed the determination of separatists to target hardened high-profile targets. We assess that such a major attack on a Chinese-funded project or interests in southern Pakistan is a likely scenario in 2021, particularly construction and extractives targets that they perceive exploit local land and resources.

Separatists intensify attacks in Pakistan

to think about Covid-19

Outliers

The assassination of the Afghan president

Monitoring Points

Consolidating power in

Sri Lanka

State elections in India

The extent to which President Gotabaya Rajapaksa pushes loyalists into key decision-making posts will indicate a how strong a swing he makes towards China in attracting investment. A constitutional amendment in late 2020 gave the president greater powers to hire and fire the prime minister and judges as well as set up commissions. It would also indicate a leaning towards a more authoritarian style of government. Good relations between him and the prime minister, who is also his brother, will ensure relative political stability in 2021.

troop withdrawals in afghanistan

Although we forecast that peace talks will probably fail, or at least not conclude in 2021, several developments may signal more positive progress. These include the Taliban agreeing to a minimum ceasefire period that suspends assaults on provincial centres. Notices of any delay to the planned US withdrawal would also signal a likely and imminent escalation in attacks in cities.

State elections in 2021 will be the first clear measure of how well the government is handling the Covid-19 outbreak in the public mind. Even if the governing BJP does not win any new states in the elections due in April-May, an increase in vote shares would signal that the pandemic, high unemployment and poor economic conditions have not hampered the party’s popularity or its agenda. In the unlikely scenario that the BJP loses all state elections in April-May, we would anticipate a slowing of reforms to incentivise investment. But such a result would make protests by farmers and informal workers less likely.

Images: Wakil Kohsar; Carl Court; Ishara S. Kodikara; Paula Bronstein; Wakil Kohsar; Kevin Frayer/Getty Images