AFRICA

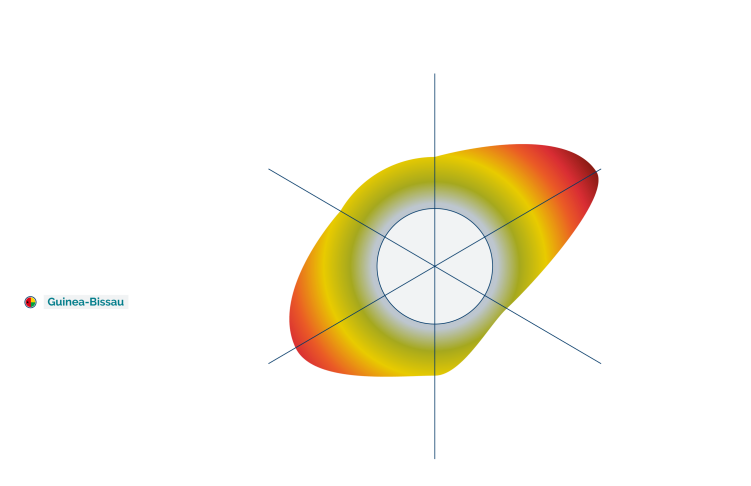

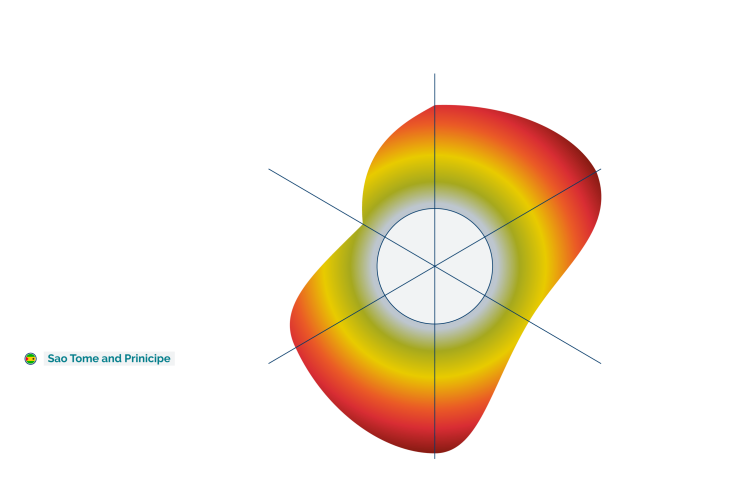

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Overall trend: Worsening

Image: Leon Neal/Getty Images

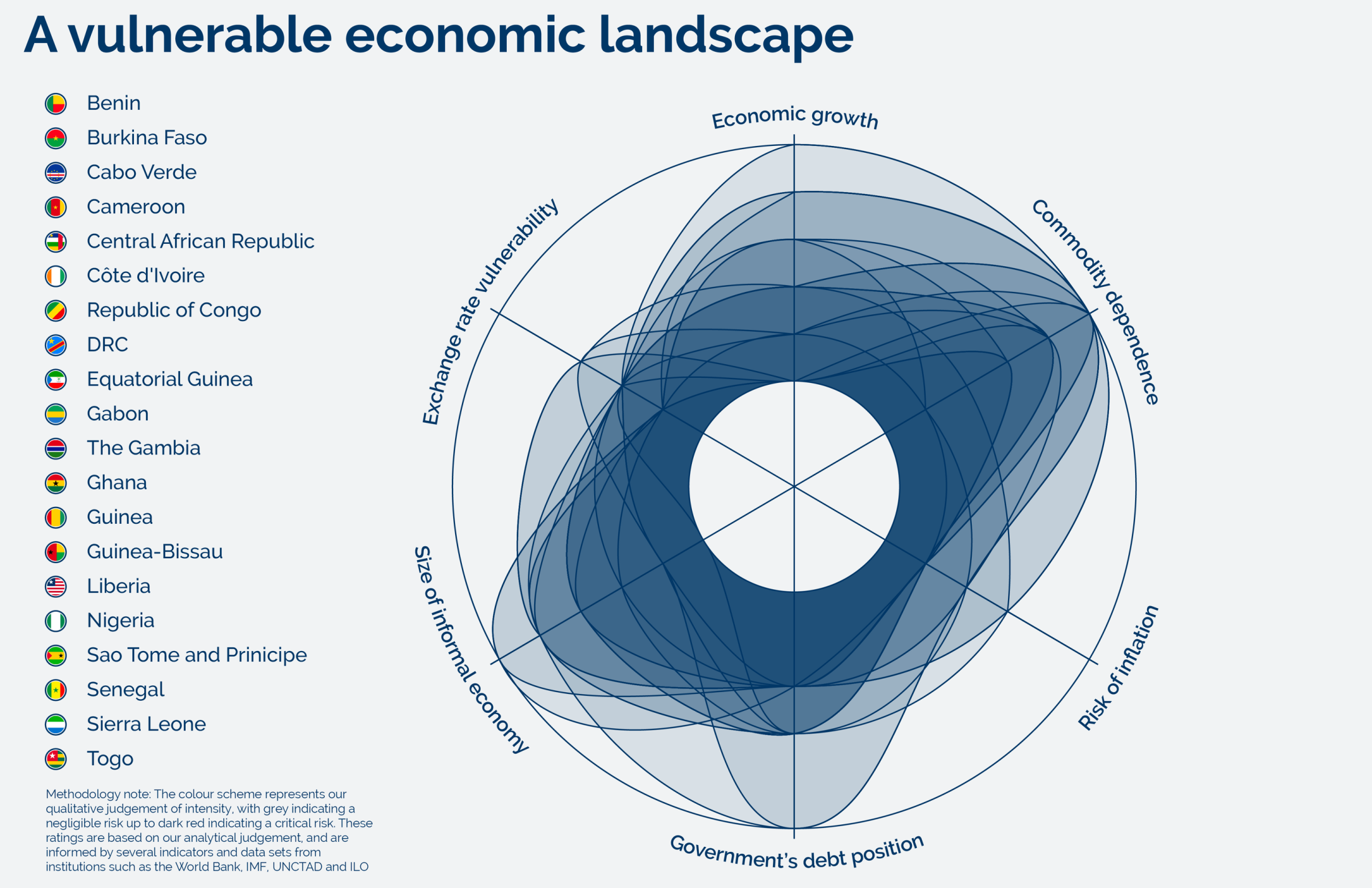

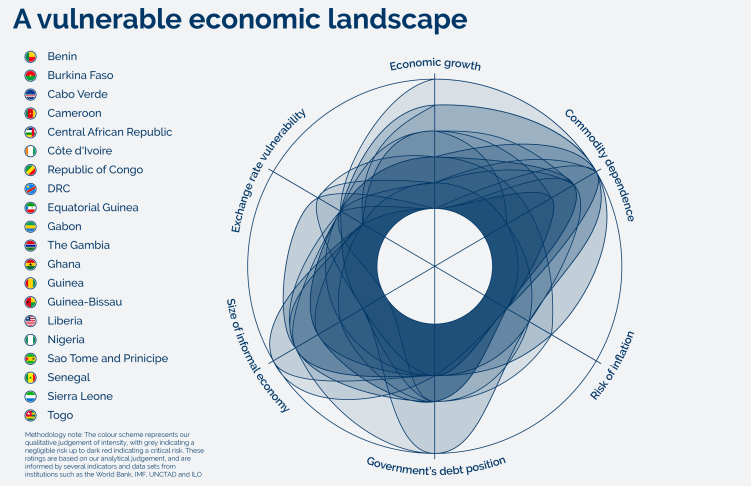

Like all the world, the broader strategic outlook for the region is pegged to the roll-out of effective Covid-19 vaccines or treatments worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africa had far lower case rates of Covid-19 than the Western hemisphere in 2020, although their economies took big hits. And in 2021, we forecast that one of the biggest strategic risks in the region is the ongoing pandemic suppressing demand for oil and other resources, and strangling revenues that enable governments to stay in power.

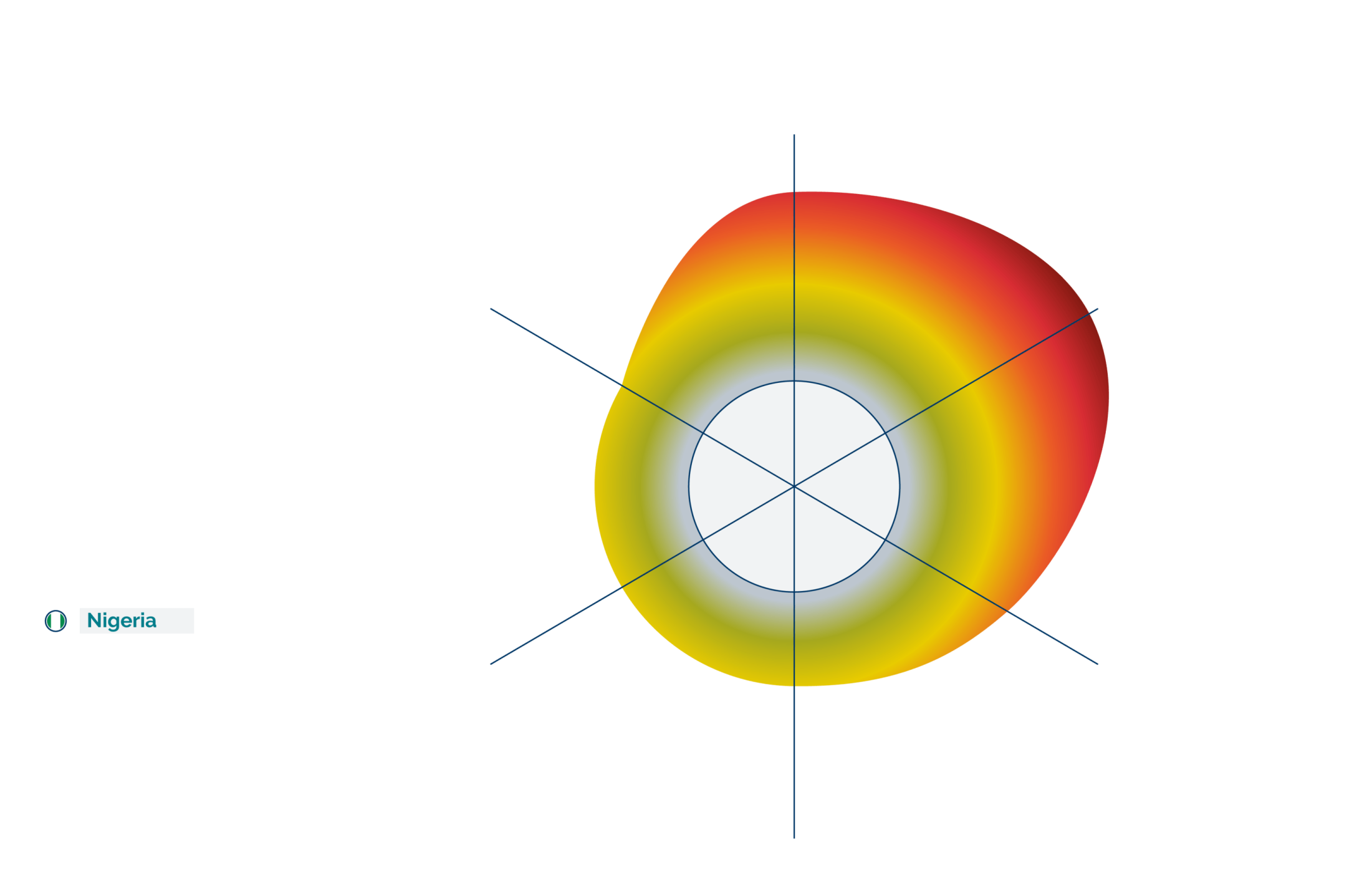

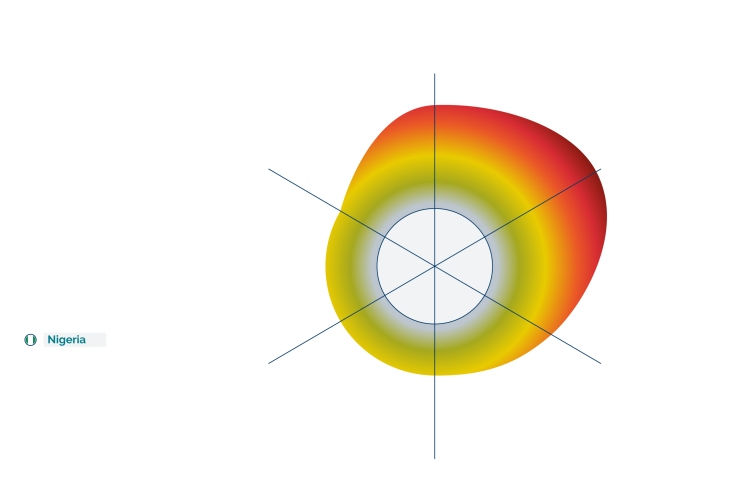

The economic fallout of Covid-19 is particularly likely to lay bare deep dysfunction and grievances in Nigeria, where oil revenues have long bailed out poor governance. The country is already in the midst of a chronic security crisis across much of the north. We forecast that in 2021, protests will make the south less stable, and also that there is potential for the whole country to experience a wave of demonstrations that could be unprecedented in how they unify different ethnic, social and

religious groups against the government and political system.

A police brutality scandal in 2020 sparked widespread anger and achieved a rare feat of uniting many Nigerians in common cause under the banner of #EndSARS. A movement mass-protesting against police violence started to widen its demands to end poor governance in Nigeria. Curfews and violence at protests suppressed this, but the potential for a broader social media-enabled protest movement to emerge and challenge the government now has a precedent. Declining revenues mean that the government’s already limited capability to address the myriad grievances of Nigerians will almost certainly erode further

in 2021.

Such unrest is very unlikely to lead to any real political change in Nigeria in 2021. But it would pose new and increased security risks on the ground, further impact the economy and stretch security resources. None of this is positive for the government's capacity to contain terrorism risks in the northeast. We also warn that insecurity in northern Nigeria will further enable Islamist extremist factions in the Lake Chad basin to develop a cross-border land bridge with groups in the Sahel, and vice versa. And more broadly, our security outlook for both the Lake Chad and Sahel areas are negative.

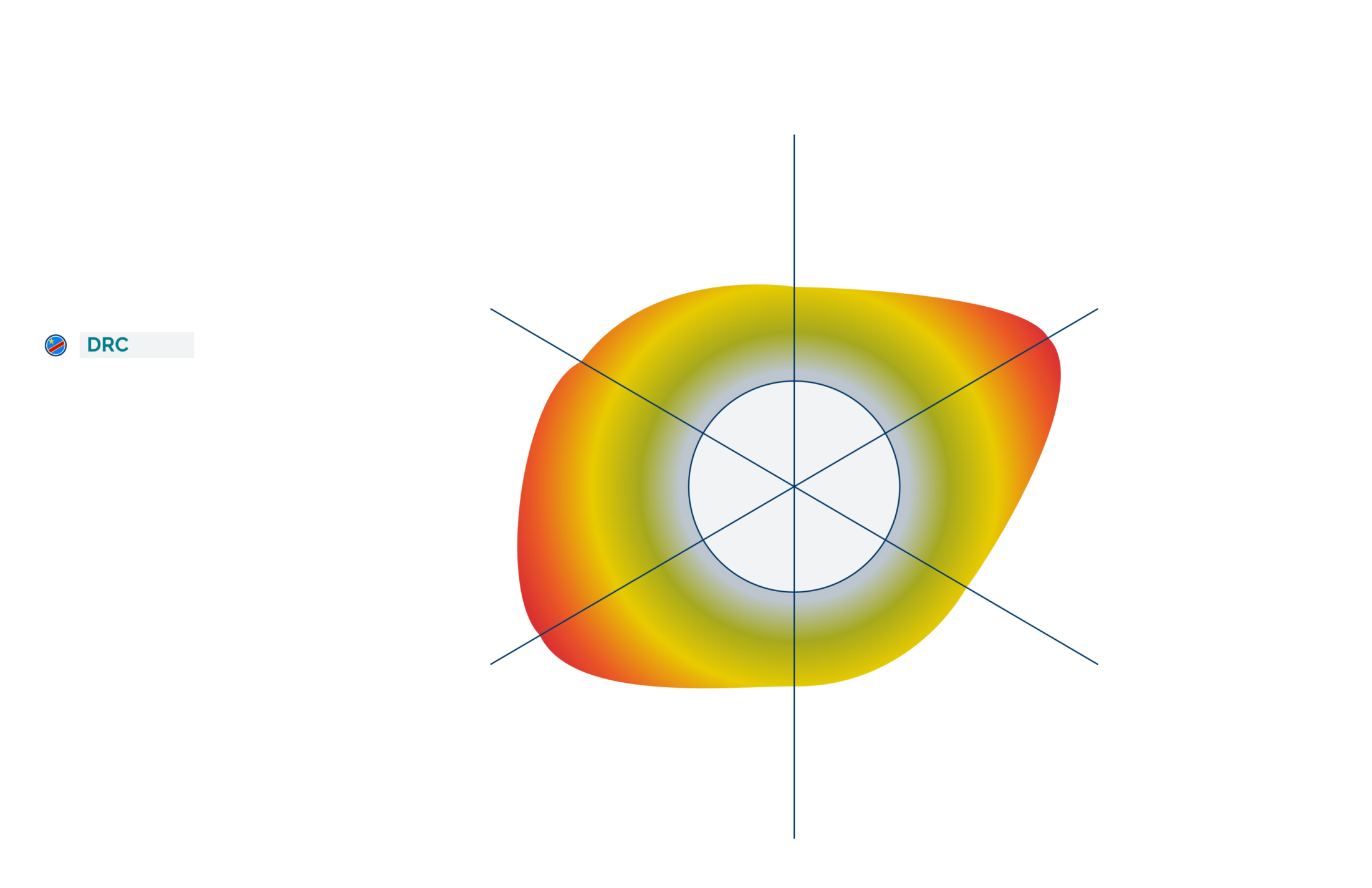

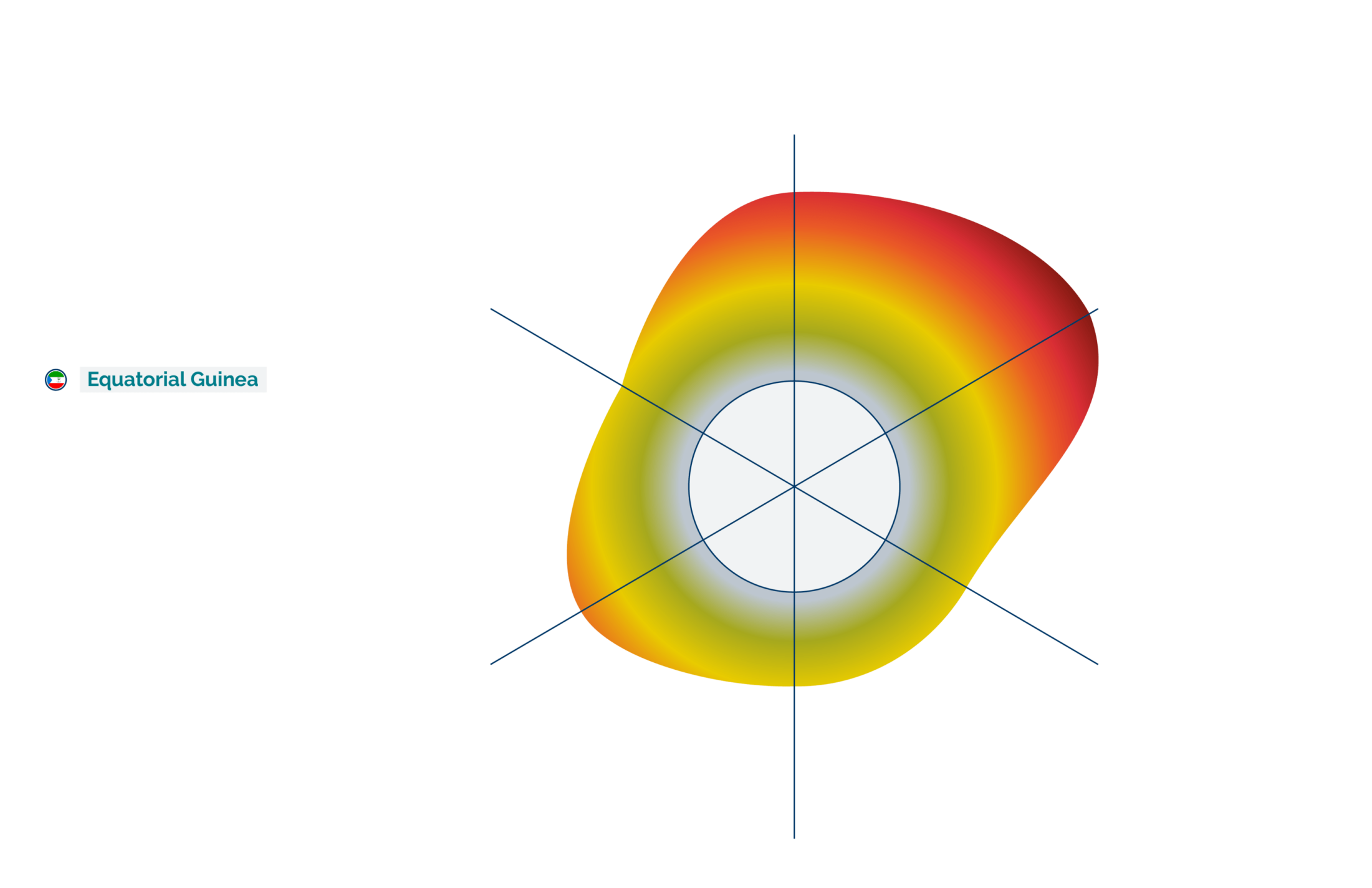

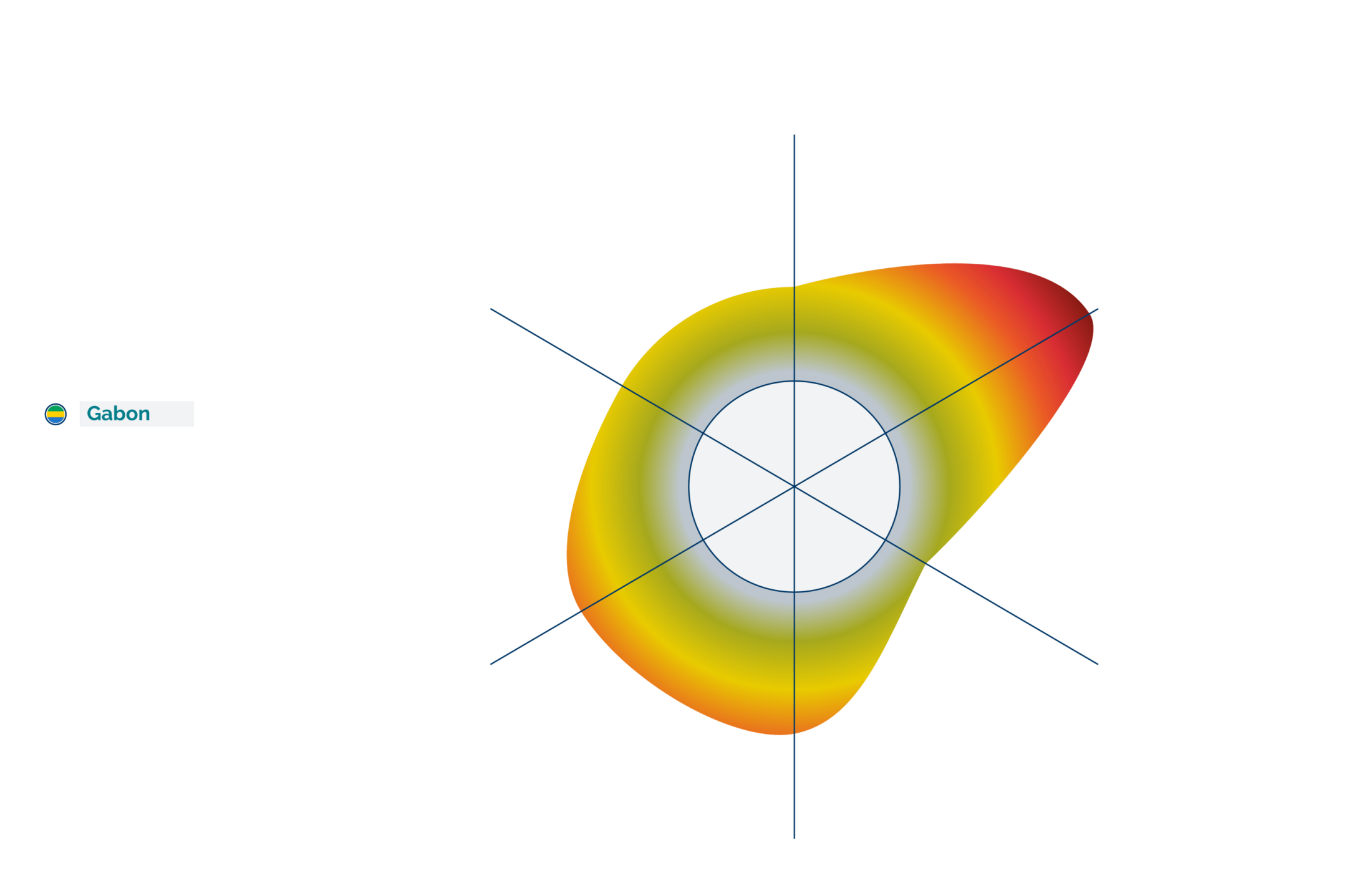

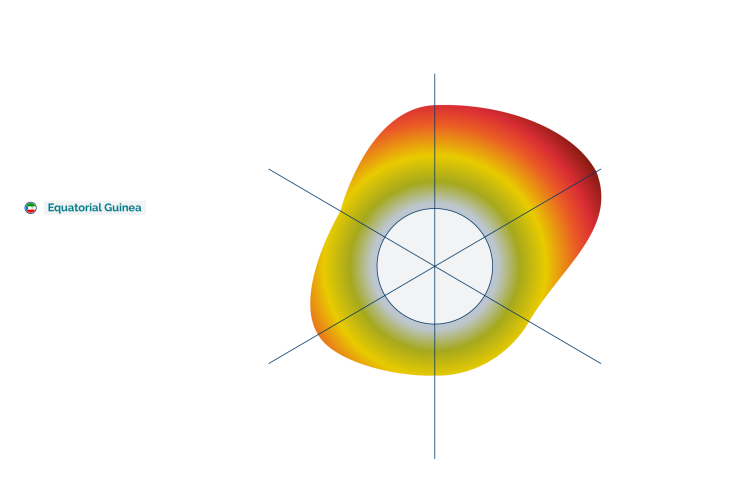

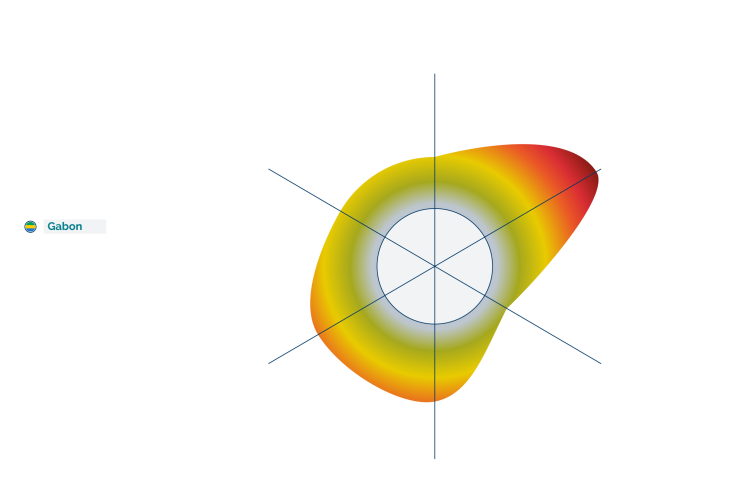

Other petro-dependent countries – namely Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of Congo – are equally exposed to what is likely to be a persisting weak oil price through 2021. And they will have few options but to cut public spending. The repressive nature of most of these governments means that such cuts would be unlikely to yield any major instability in 2021. But we anticipate a baseline rise in the risks of hardship protests, crime and corruption in all of these countries through the year. And spending cuts would be highly damaging to the fabric of society in the longer term.

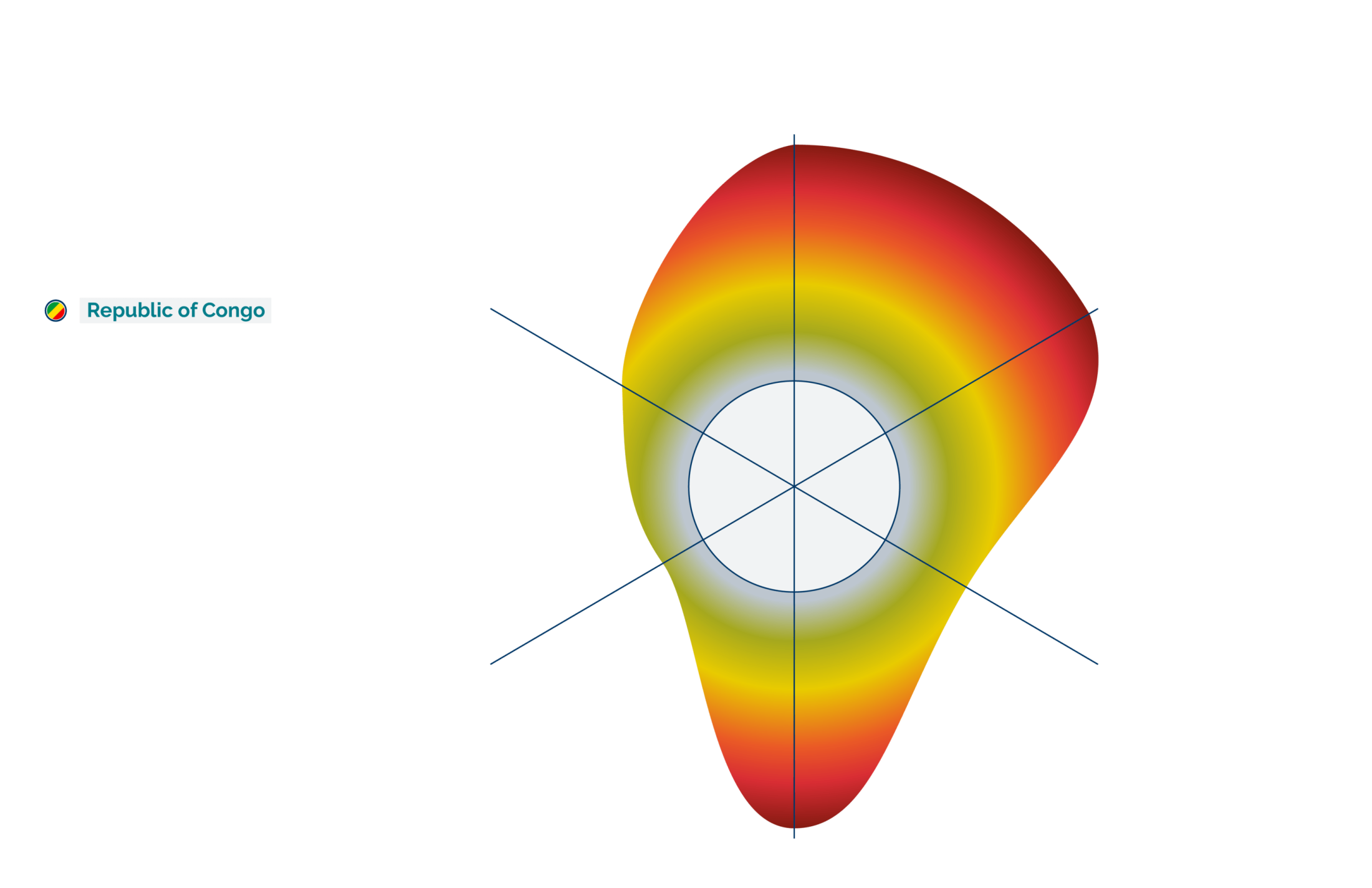

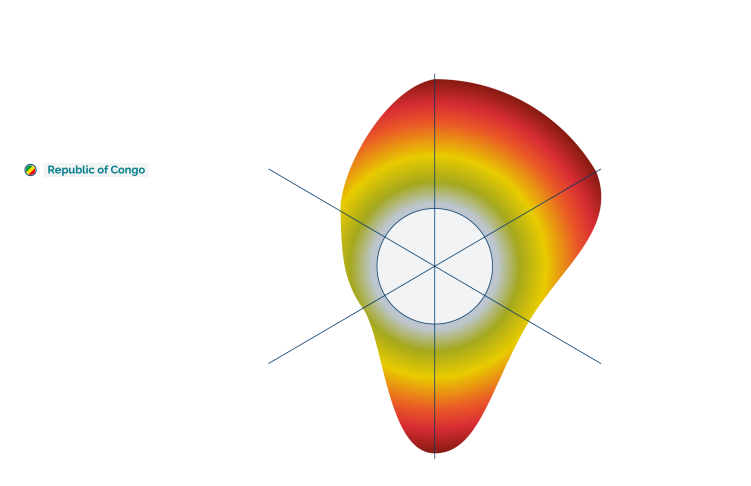

While a governance crisis in the Republic of Congo is unlikely, we nevertheless warn that an unsettled period is likely to foreshadow and follow a presidential election at some point in 2021. A date is yet to be set, but we anticipate that the polls will open in the second half of the year when the incumbent, President Denis Sassou Nguesso, will undoubtedly secure yet another term.

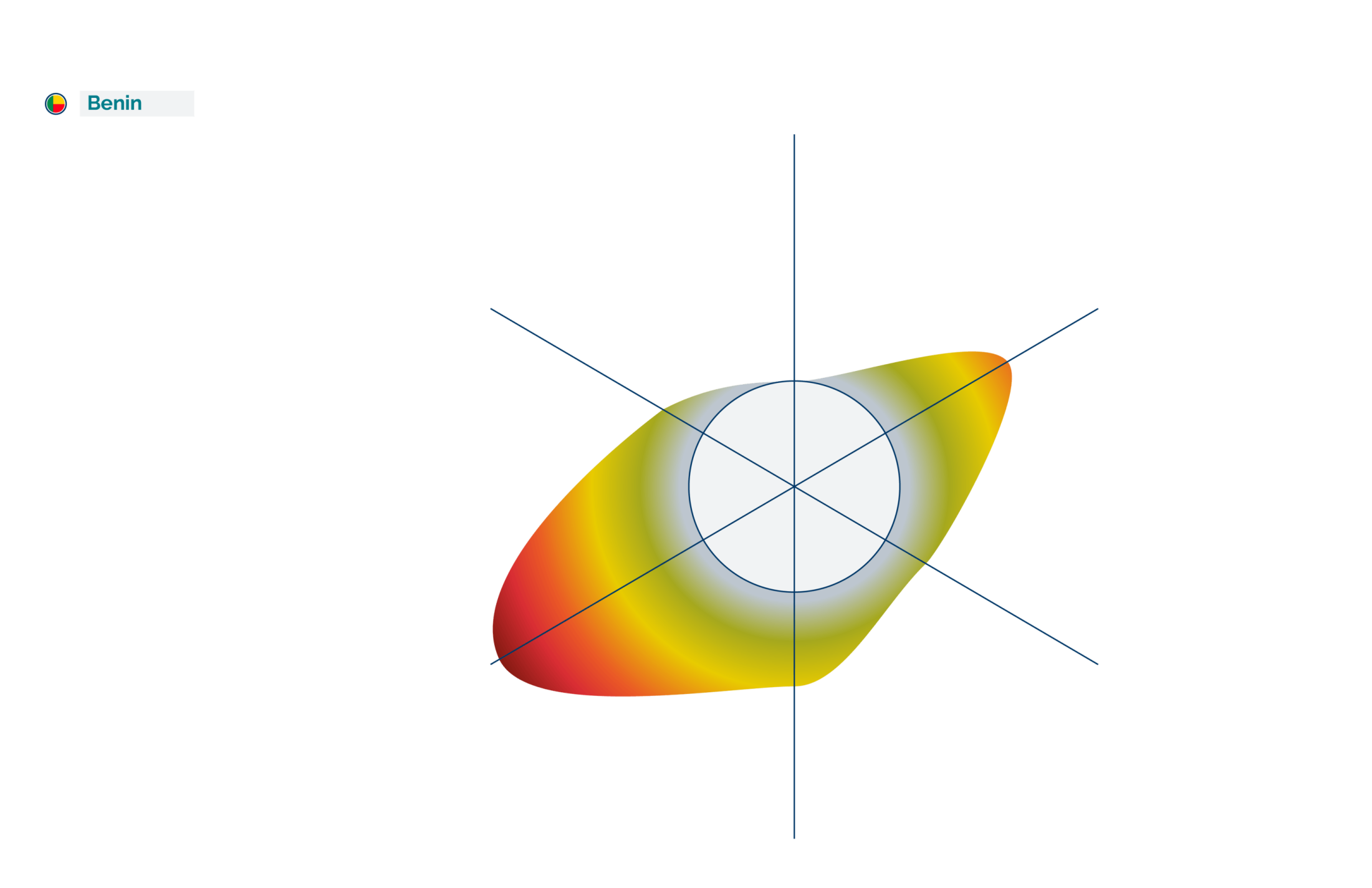

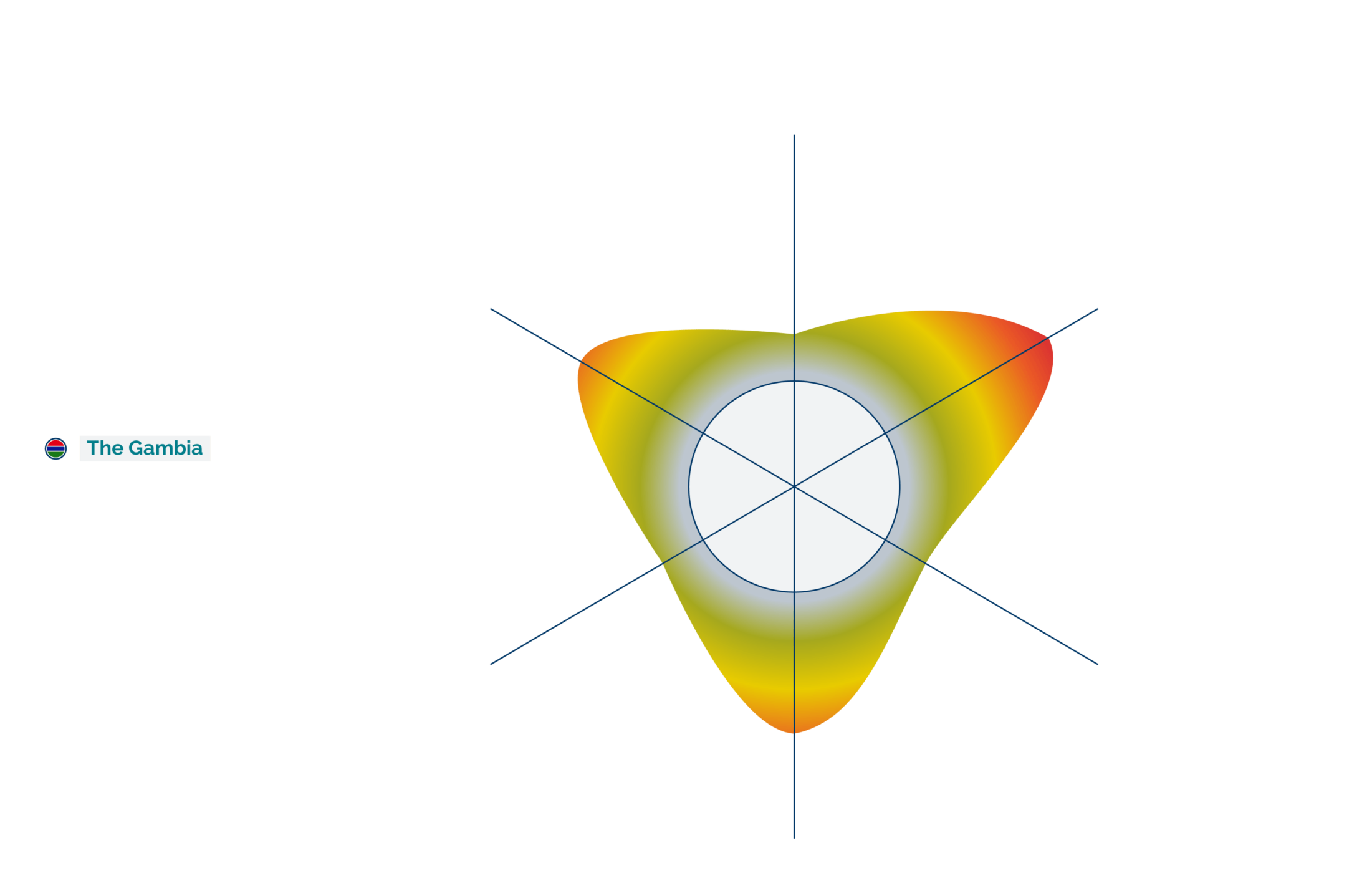

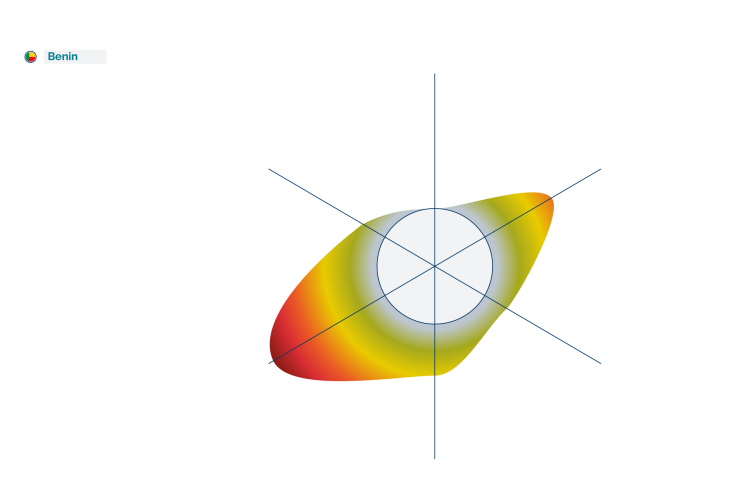

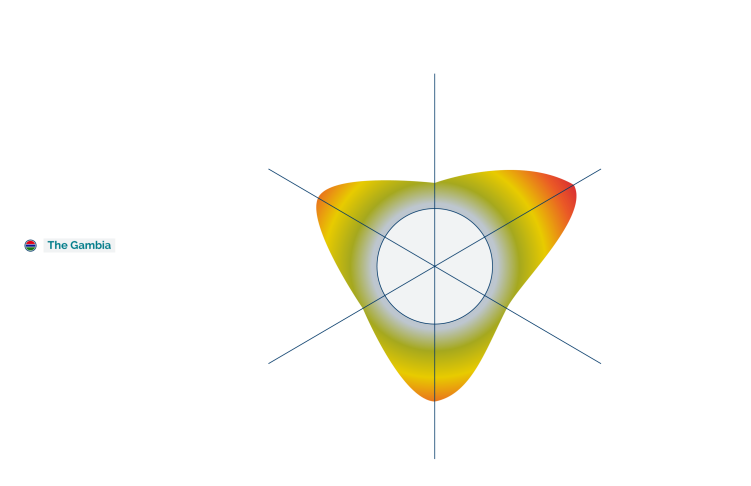

Elections in both Benin and The Gambia will probably also bring about an increased risk of instability. Recent crackdowns on the opposition

in Benin will almost certainly feed into a narrative that a presidential poll due there in the first quarter will not be free and fair. The incumbent, Patrice Talon, may well be the only candidate. And we forecast that he will secure a second term at the poll. This will probably trigger protests. And in The Gambia, we also anticipate demonstrations in Banjul and Serekunda if President Adama Barrow announces he will run for a second term. These would be unlikely to be particularly large or long-lasting, however.

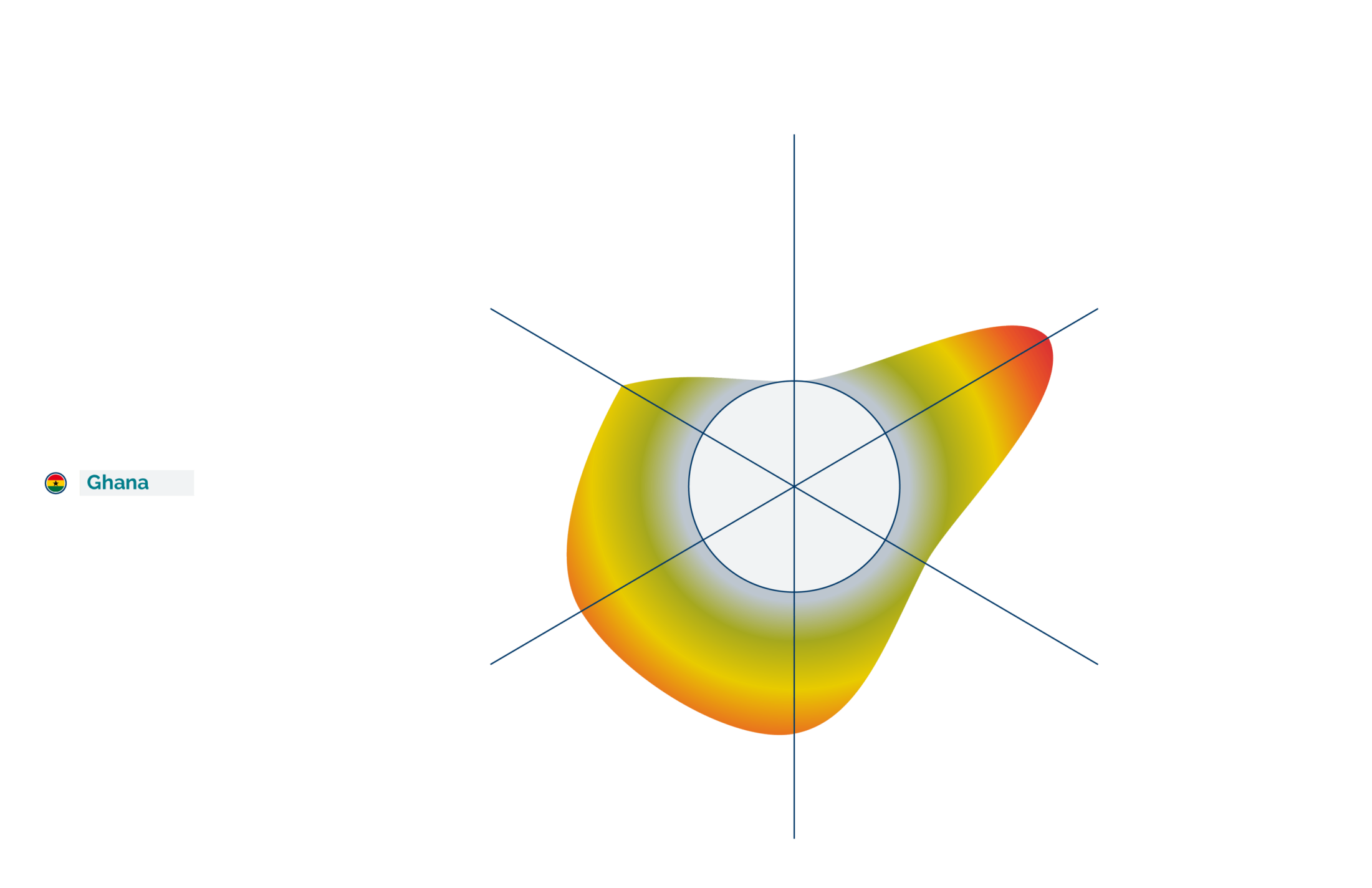

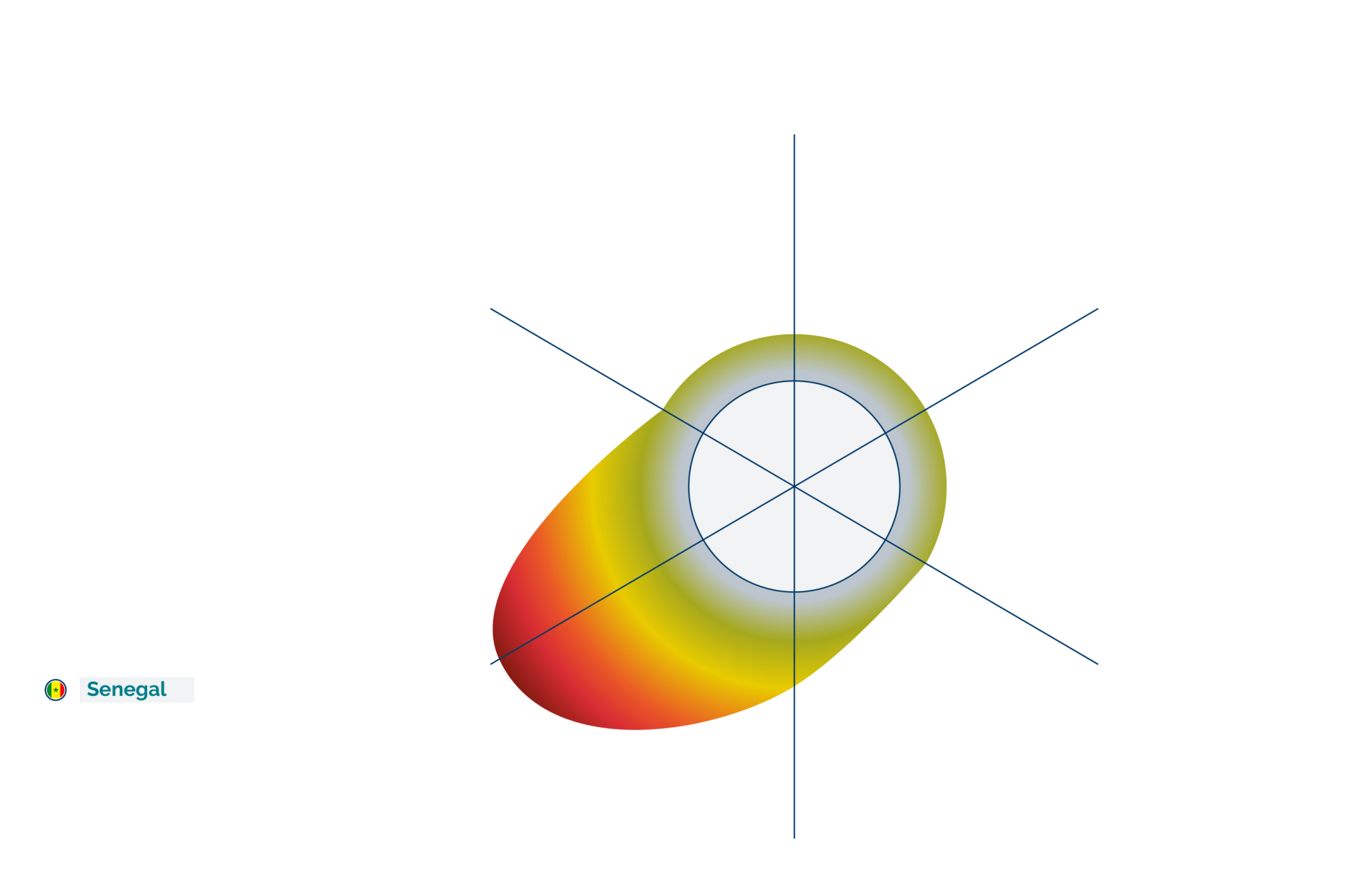

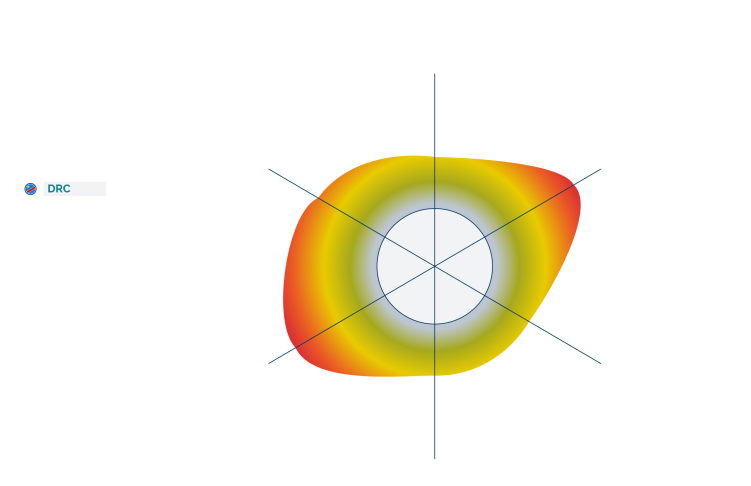

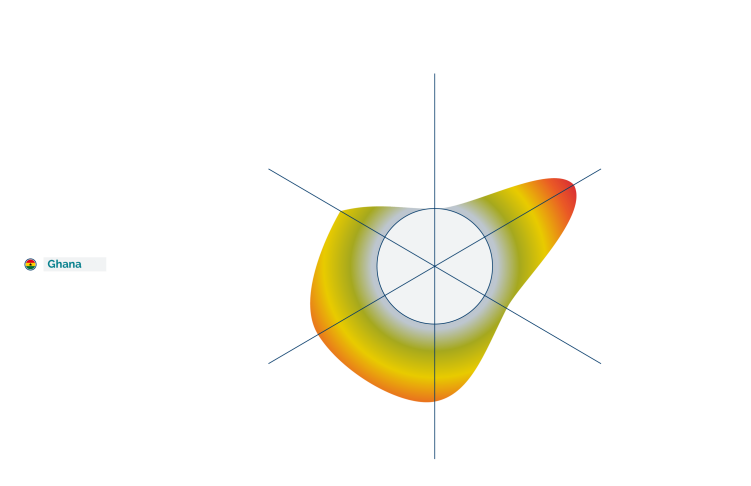

The outlook is more positive for those countries that profit from surging demand in the few commodities that offer safe havens amid the pandemic. Continued demand for gold and other goods are likely to leave both Ghana and Senegal fairly well placed economically in 2021. While the threat of terrorism is likely to be high in Senegal, neither country has any probable flashpoints that we assess will lead to political upheaval in the coming year. Revenues from cobalt exports will probably sustain an uneasy status quo between President Tshisekedi and the former president, Joseph Kabila in the DRC. The main risk of instability will be as politicking continues to build ahead of a presidential election in 2023.

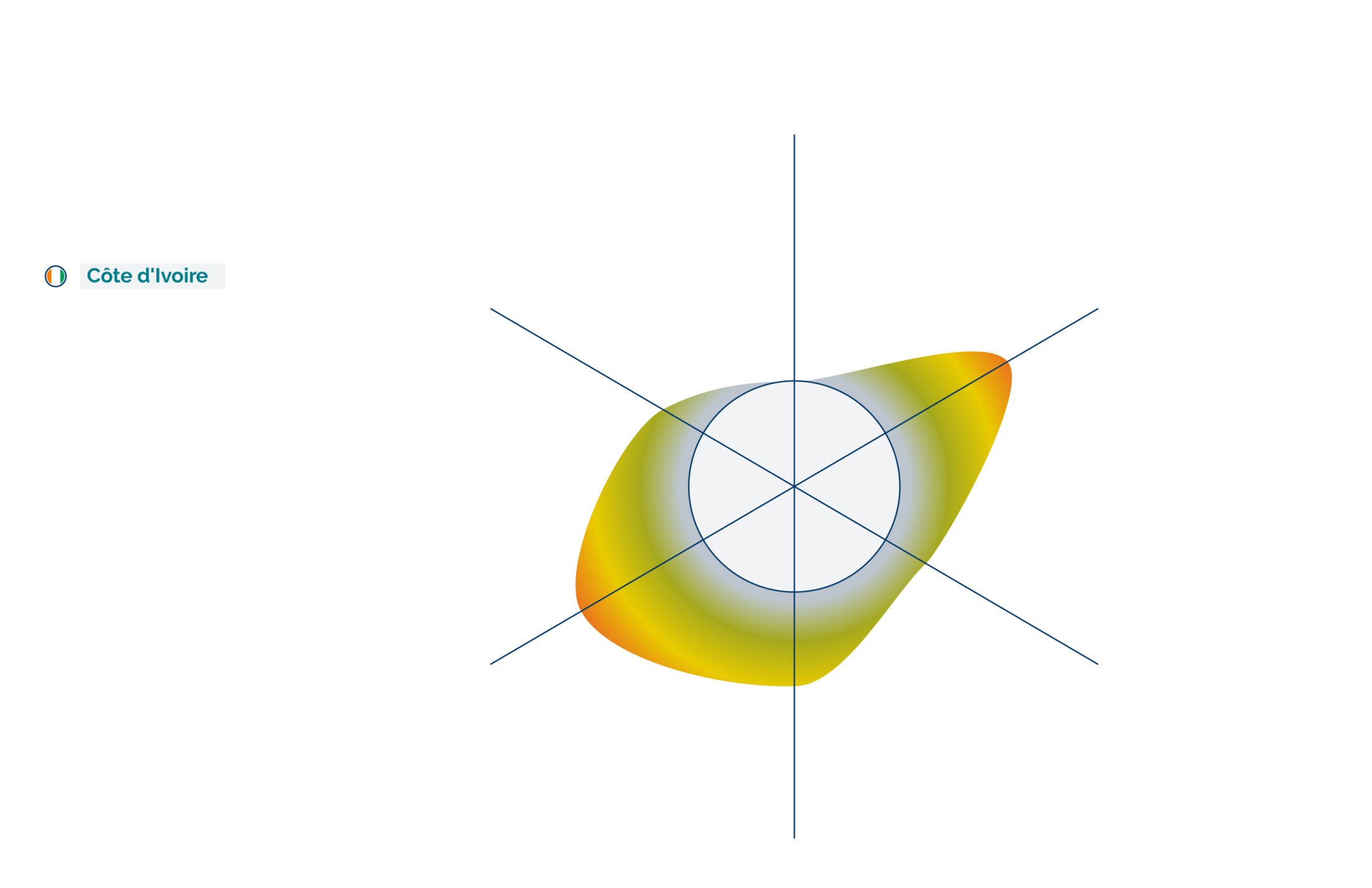

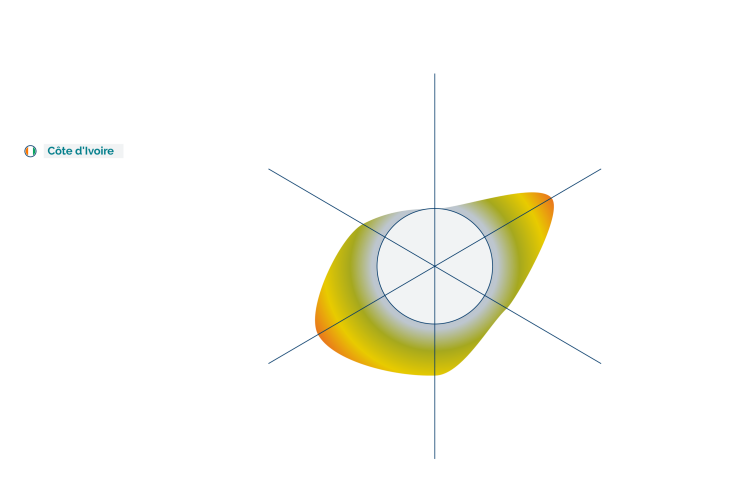

Cote d’Ivoire should also enjoy similar revenues and stability prospects. But its fortunes in 2021 will strongly depend on the extent to which President Ouattara can find a way to placate the opposition which does not recognise his third term. Further talks and meditation are likely in the first half of the year. But unless the opposition formally accepts Mr Ouattarra’s third term or there is some kind of power sharing agreement, we would expect pockets of ethnic violence to breakout and become more frequent. This is an avoidable conflict but it has every potential to be the most disruptive crisis in the region in 2021.

Declining revenues mean that the government’s already limited capability to address the myriad grievances of Nigerians will almost certainly erode further in 2021.

Image: Arsene Mpiana/Getty Images

Image: Pius Utomi Ekpei/Getty Images

Forecasts

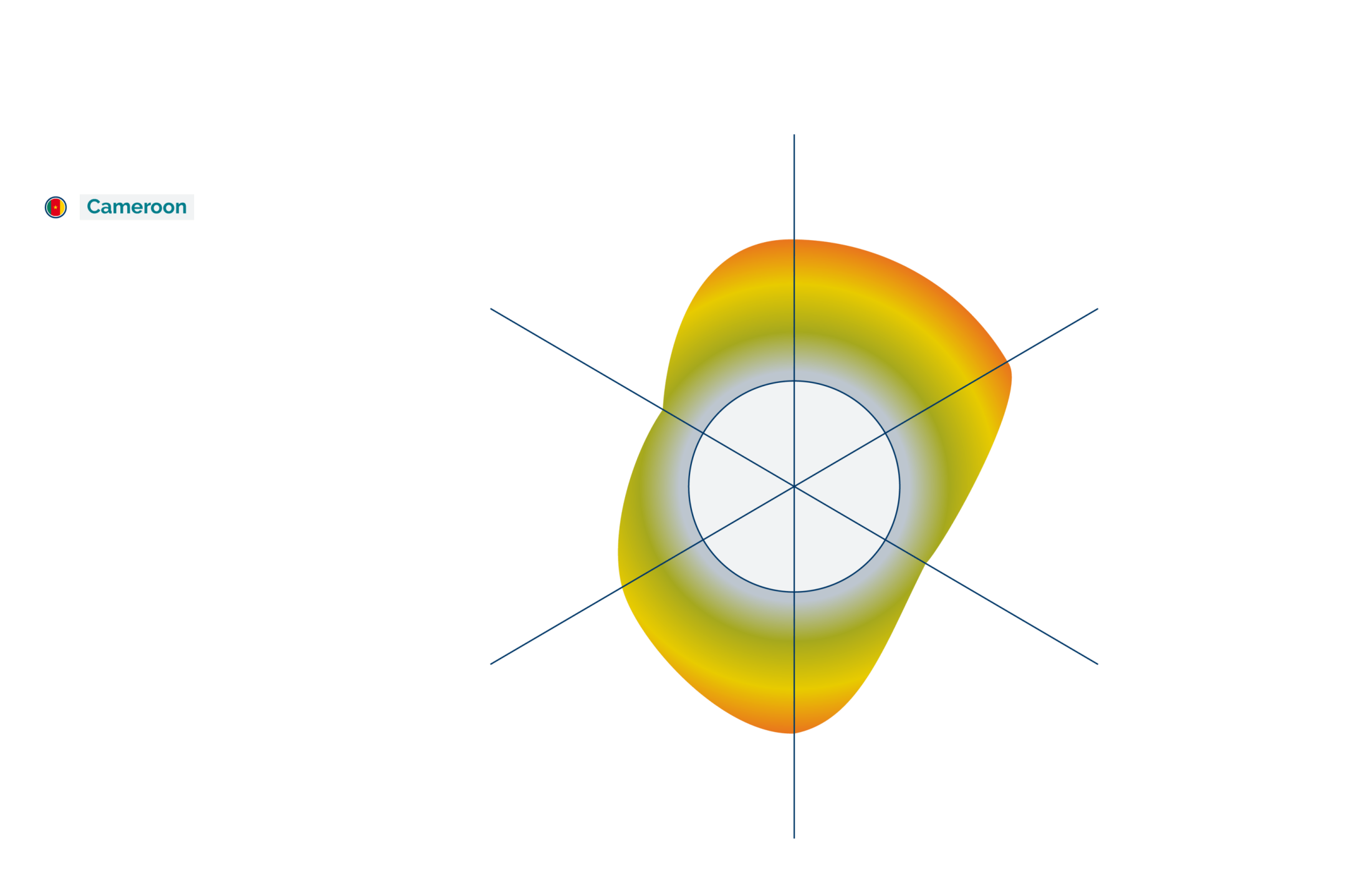

An insurgency by Anglophone separatists in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon is likely to continue throughout 2021. There will probably be increased pressure on the government to engage with militants to seek a political solution to the conflict. It is possible that moderate separatist factions would participate in talks. But the disparate nature and demands of Anglophone groups more broadly means that any deal would be highly unlikely to bring about an end to violence in the two regions.

Continuing conflict in Cameroon

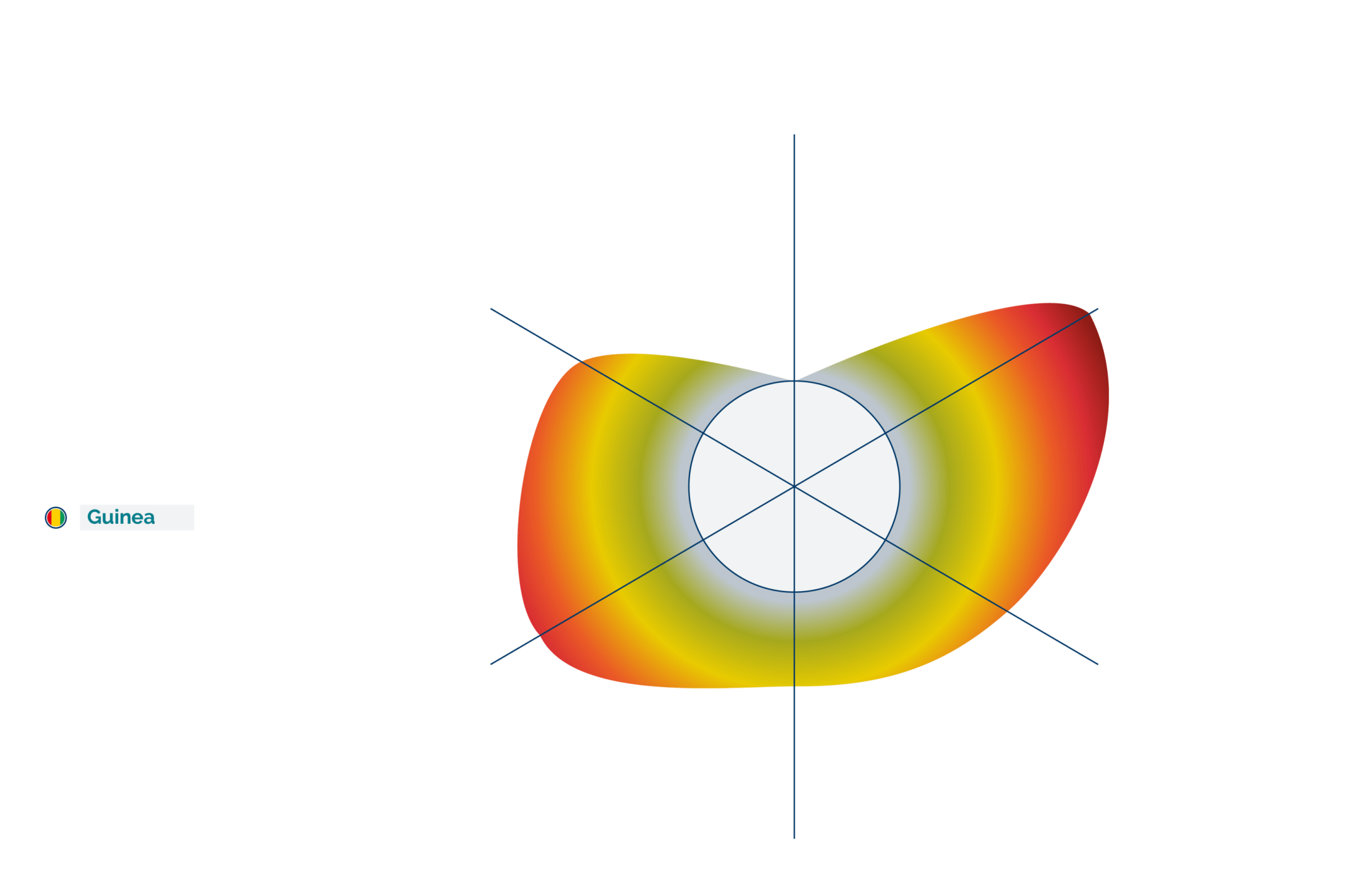

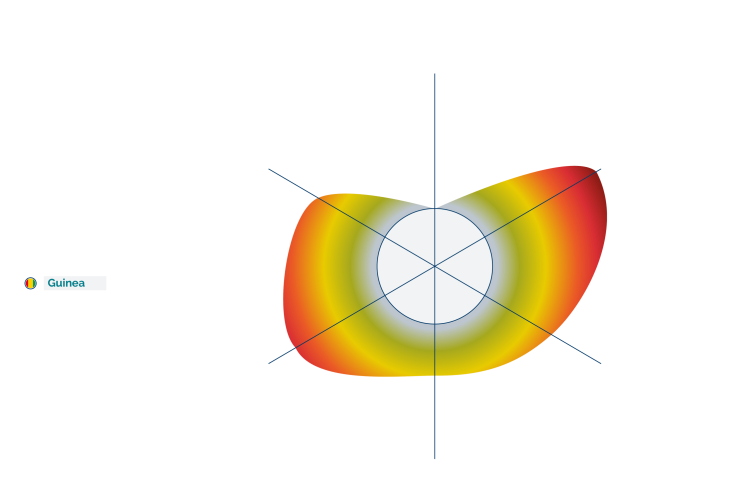

Guinea is likely to move on from several years of political crisis in 2021, following President Alpha Conde’s victory at an election in late-2020. Although the opposition has emerged from the crisis more divided than before it, we anticipate that activists will try to mobilise people over a range of other issues. These include corruption, poor government services, socio-economic conditions and to demand electoral or constitutional reforms. This will probably lead to disruptive and violent protests in Conakry through 2021, albeit less frequently than in previous years.

Improving outlook in Guinea

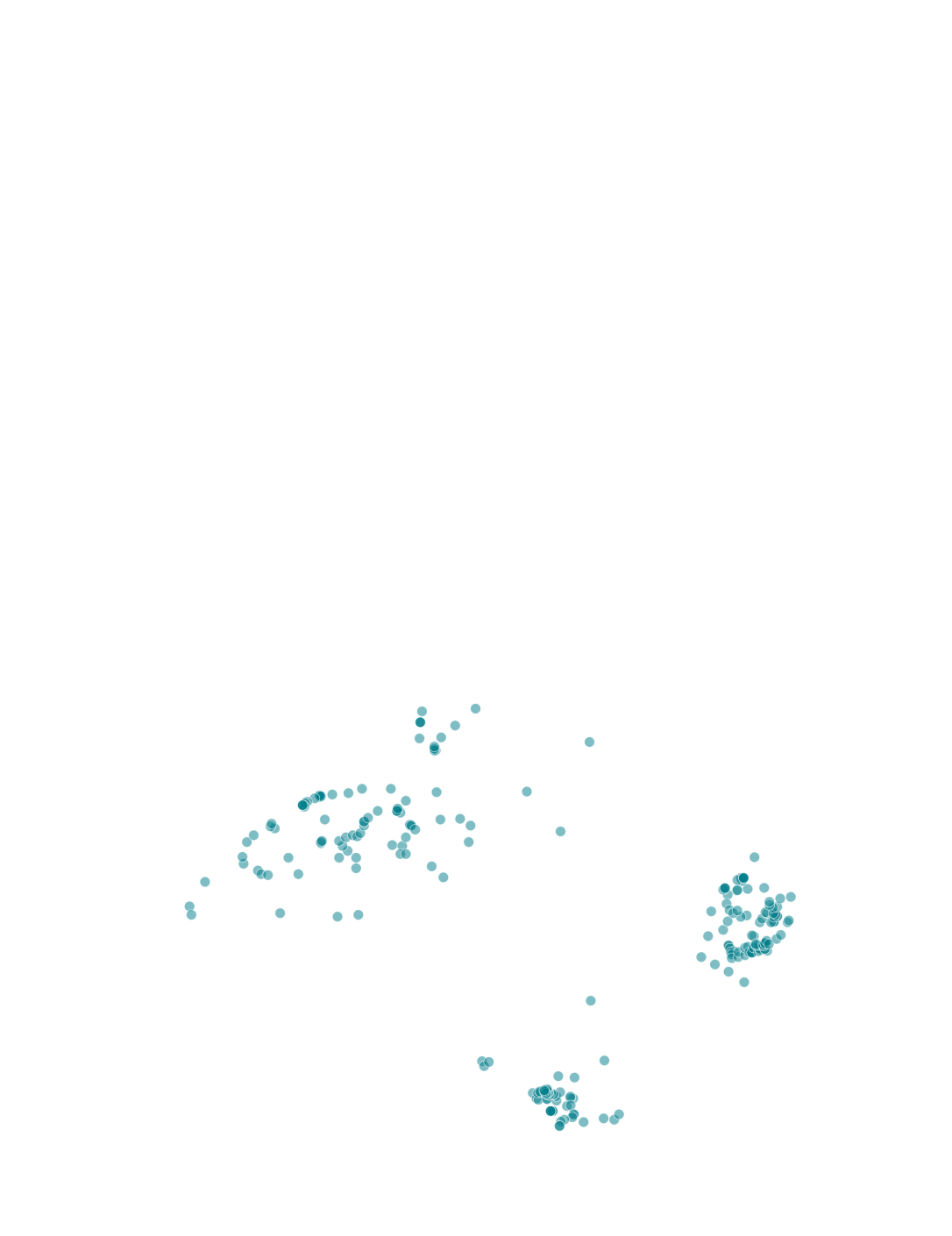

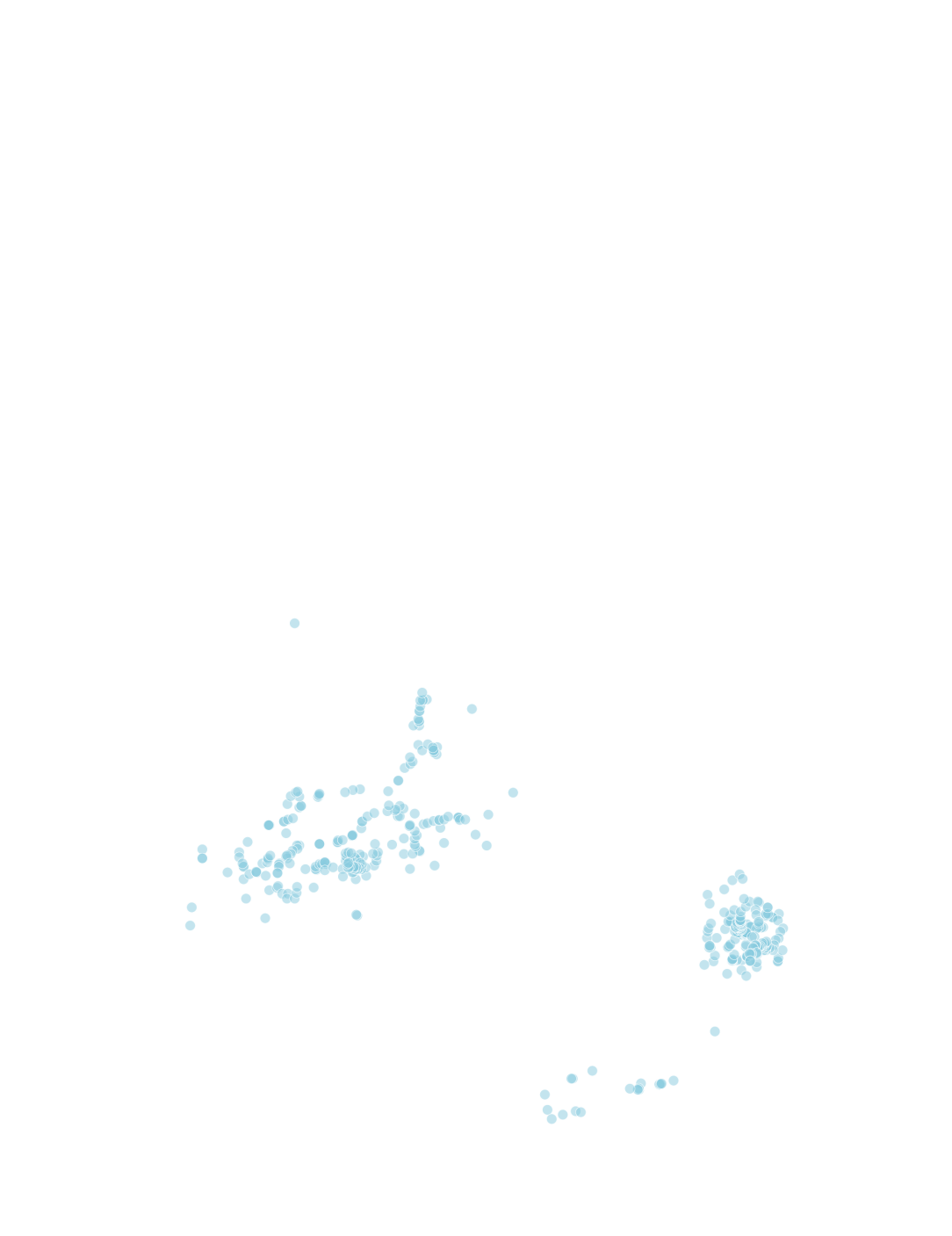

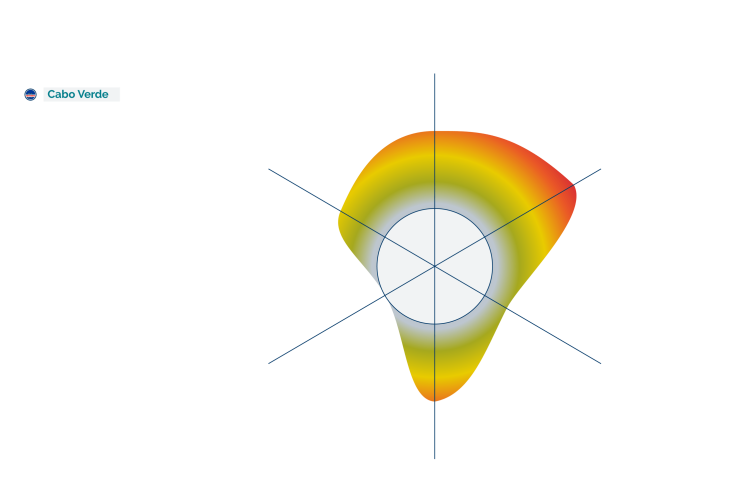

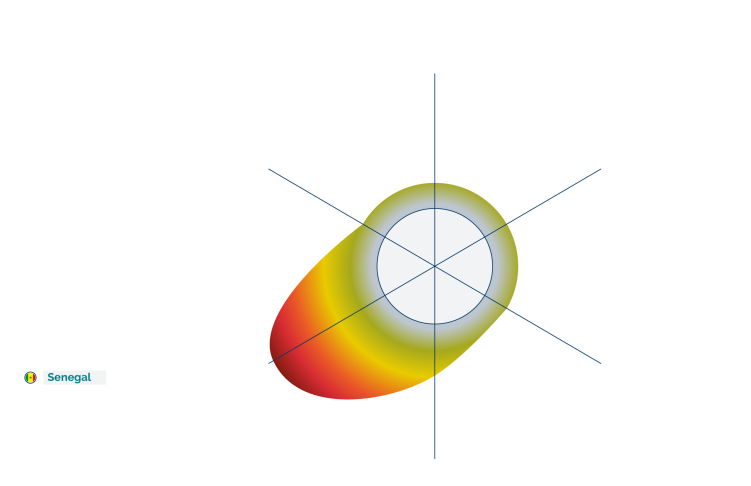

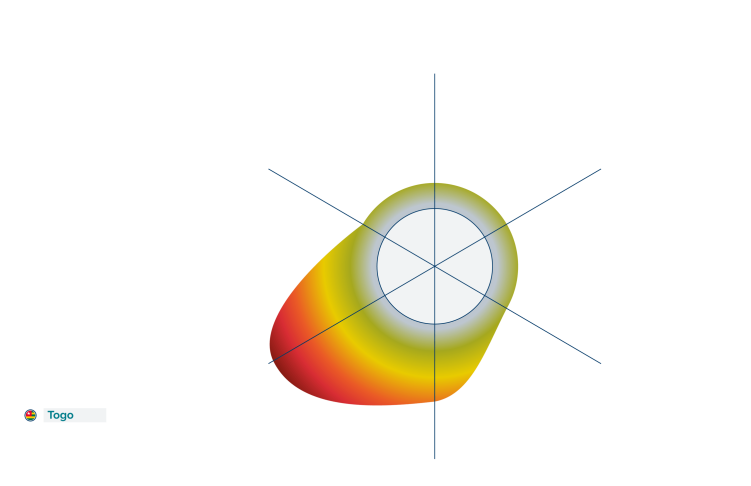

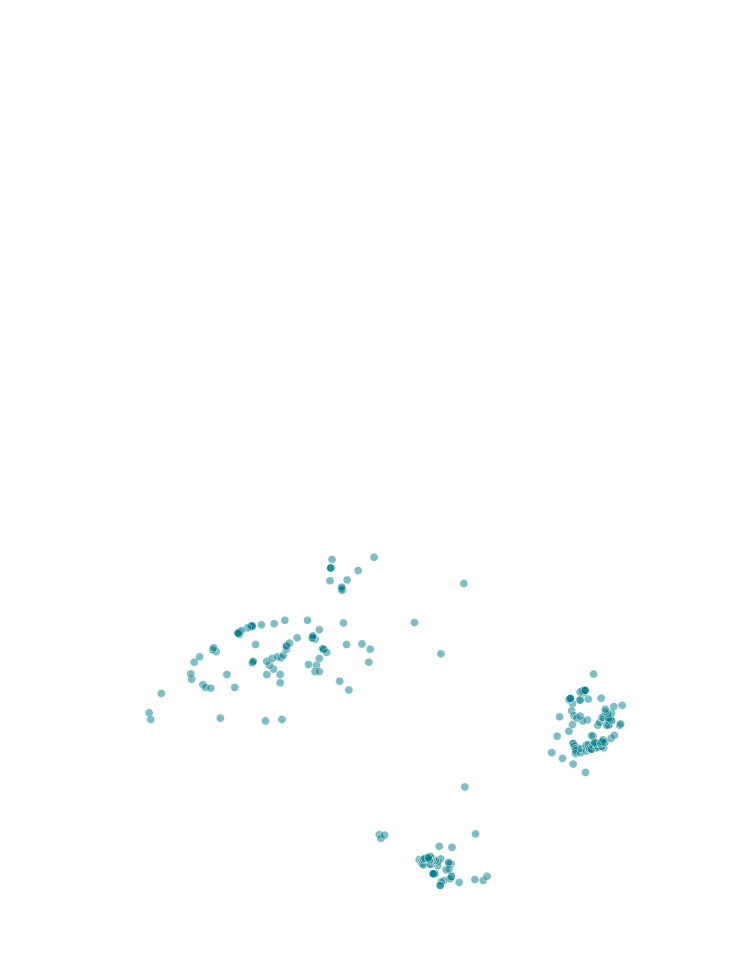

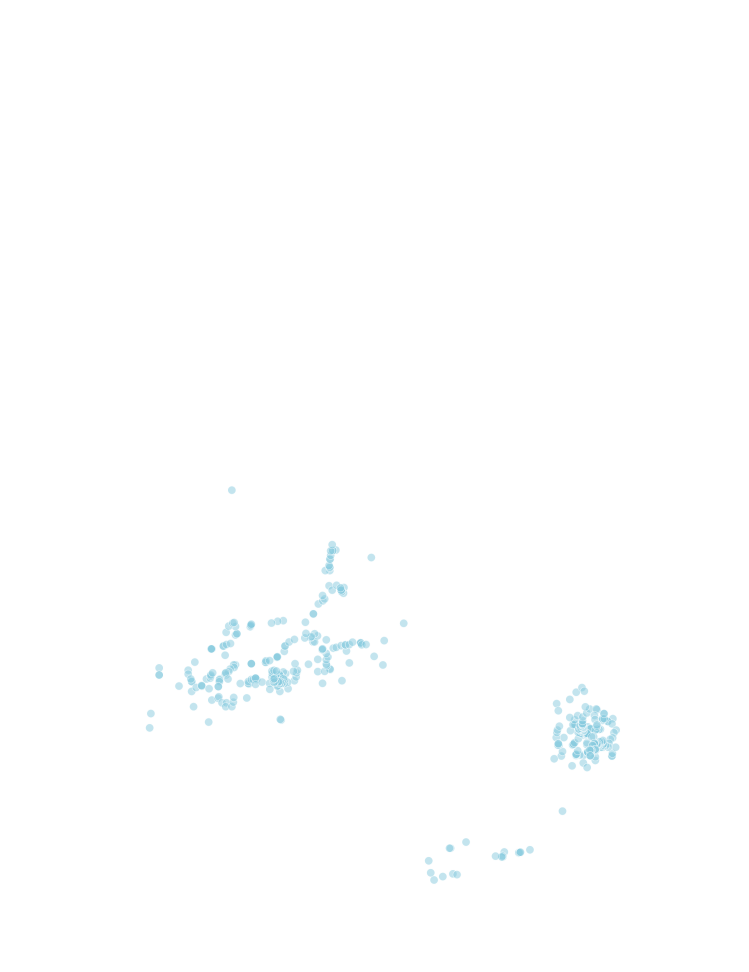

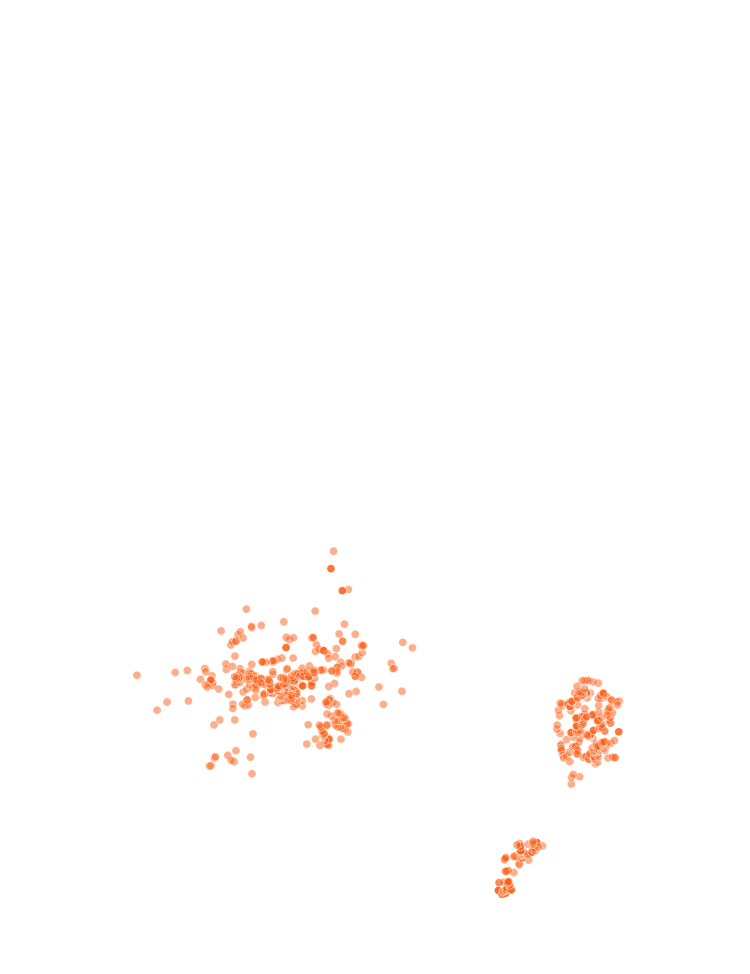

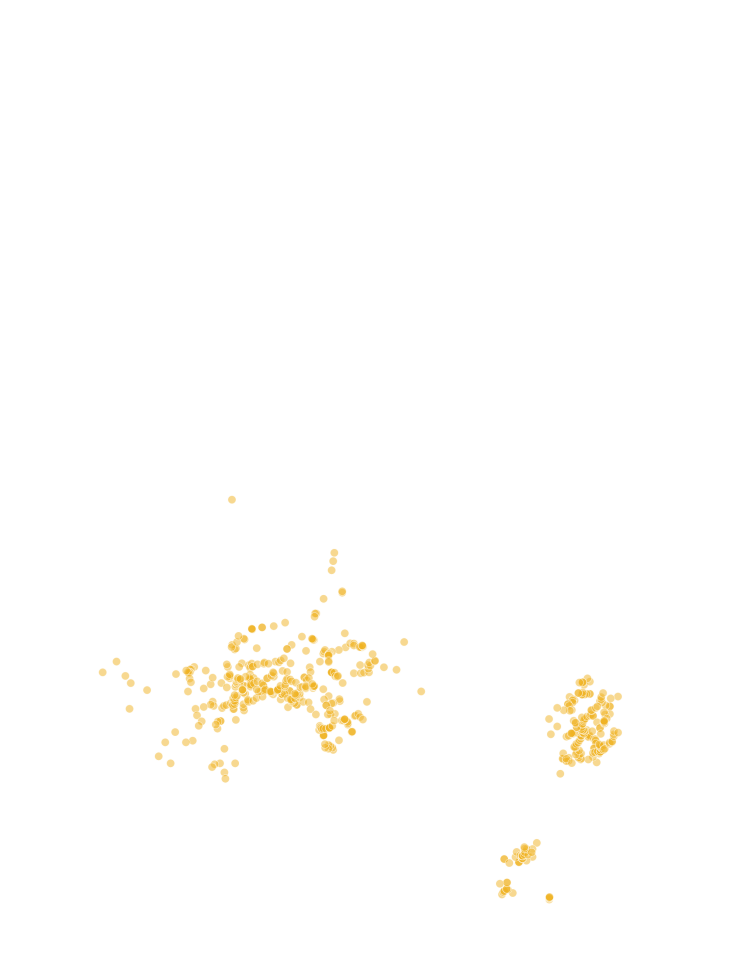

It is likely that militants linked to Al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM will attempt to expand their operational reach into Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal in 2021. Insurgents mounted an attack in the northern border area of Côte d’Ivoire for the first time in 2020. We anticipate more. We also assess that there is a reasonable chance that militants will try to launch a first attack in border areas of Senegal, and also potentially a more high-profile attack in Dakar or Abidjan targeting places popular with foreigners, such as hotels.

Spread of terrorism into Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal

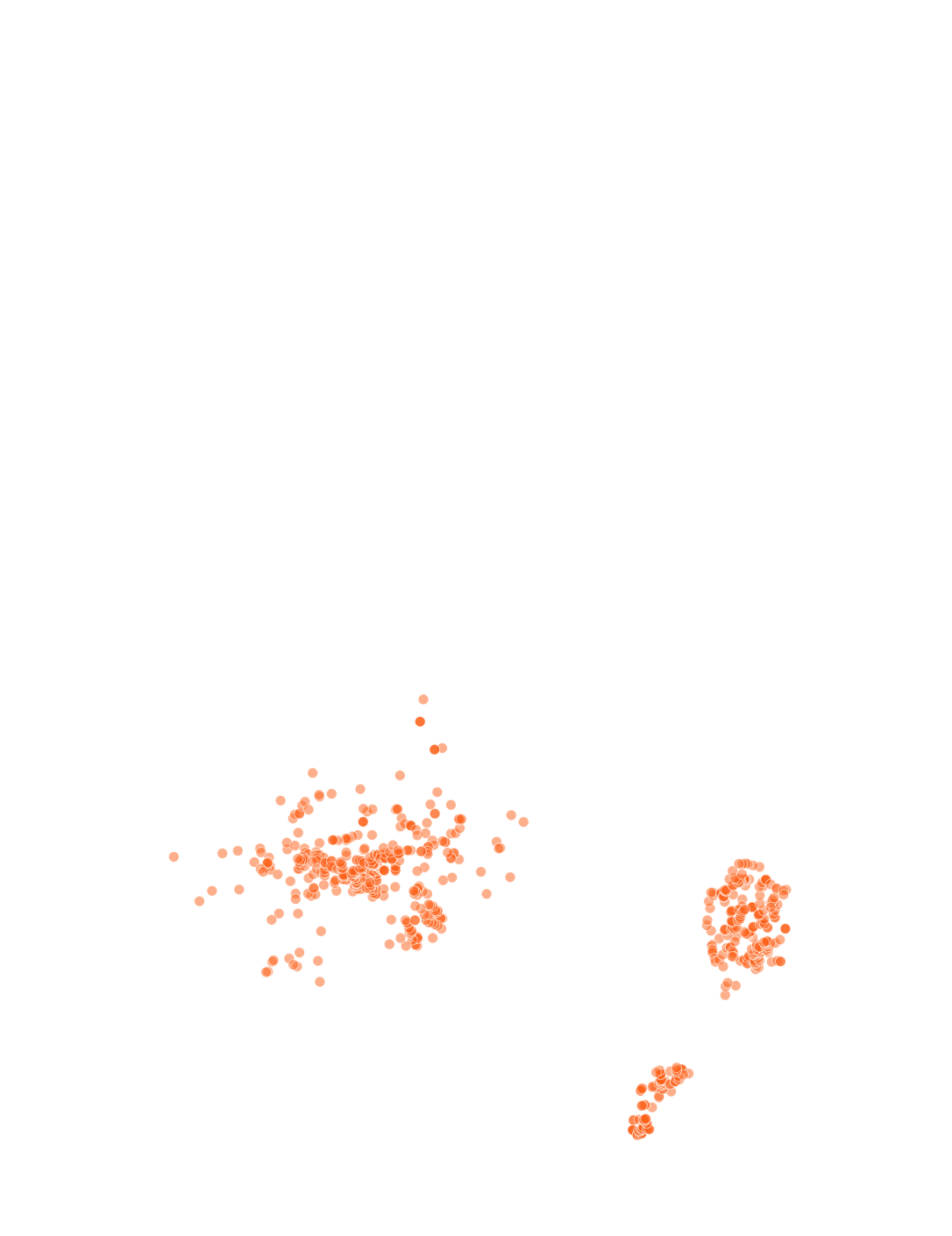

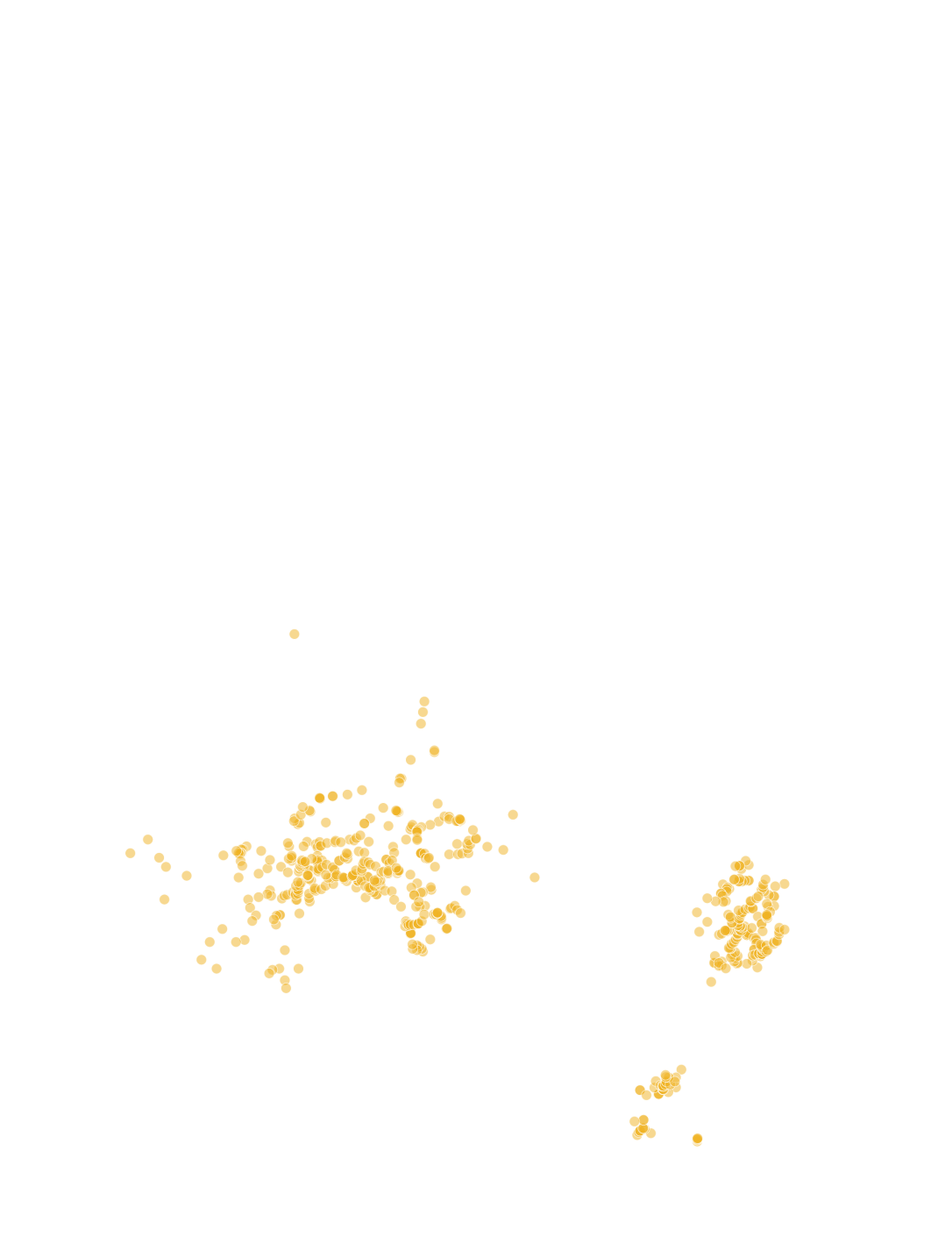

Source: Risk Advisory TerrorismTracker

Outliers

Re-emergence of insurgency in the Republic of Congo

Monitoring Points

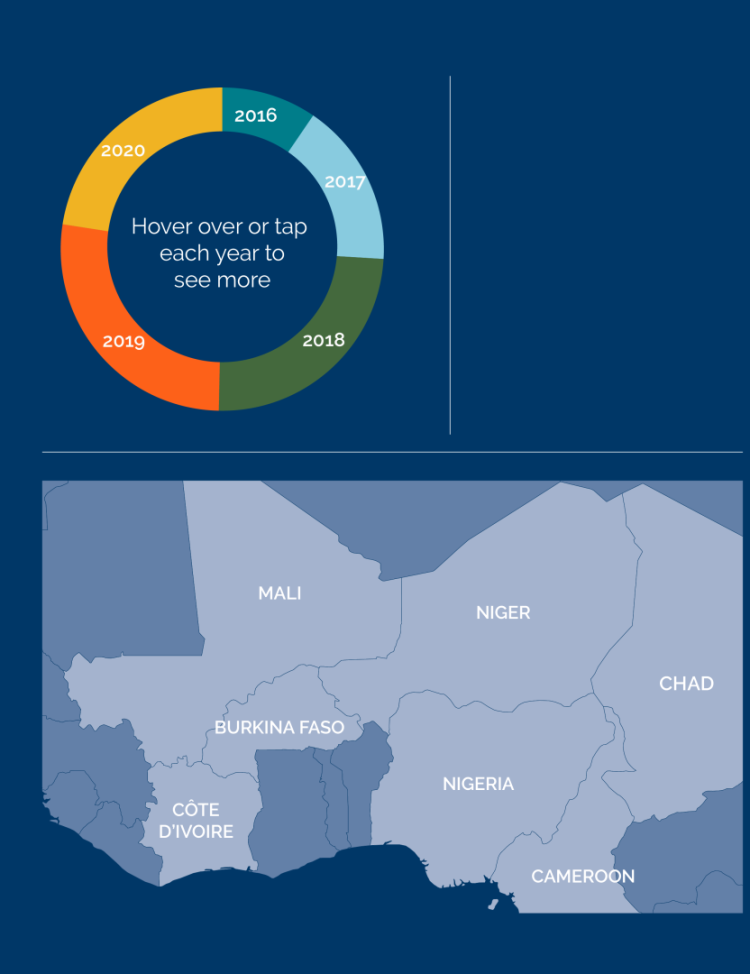

Displacement in the Sahel and Lake Chad

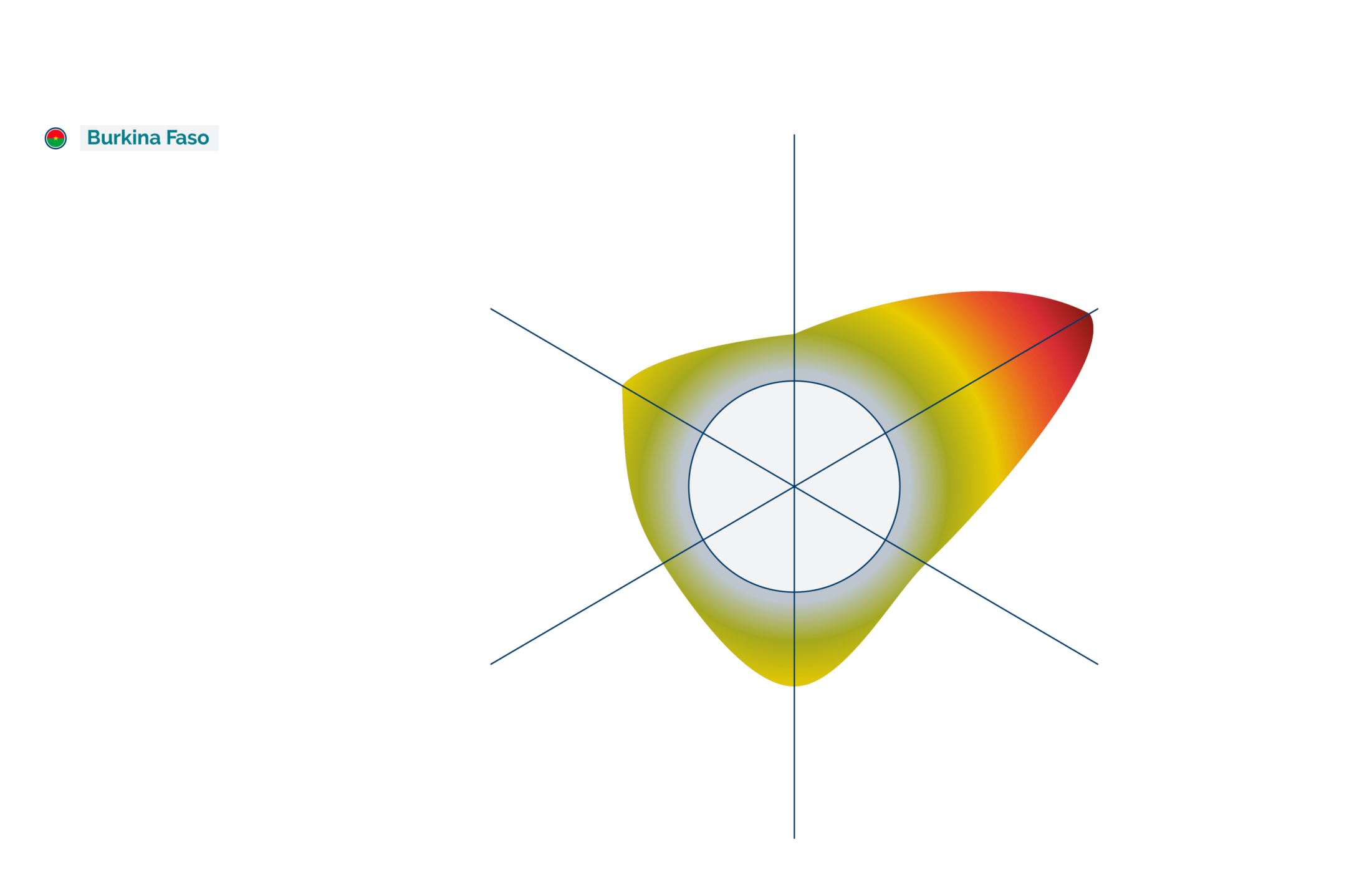

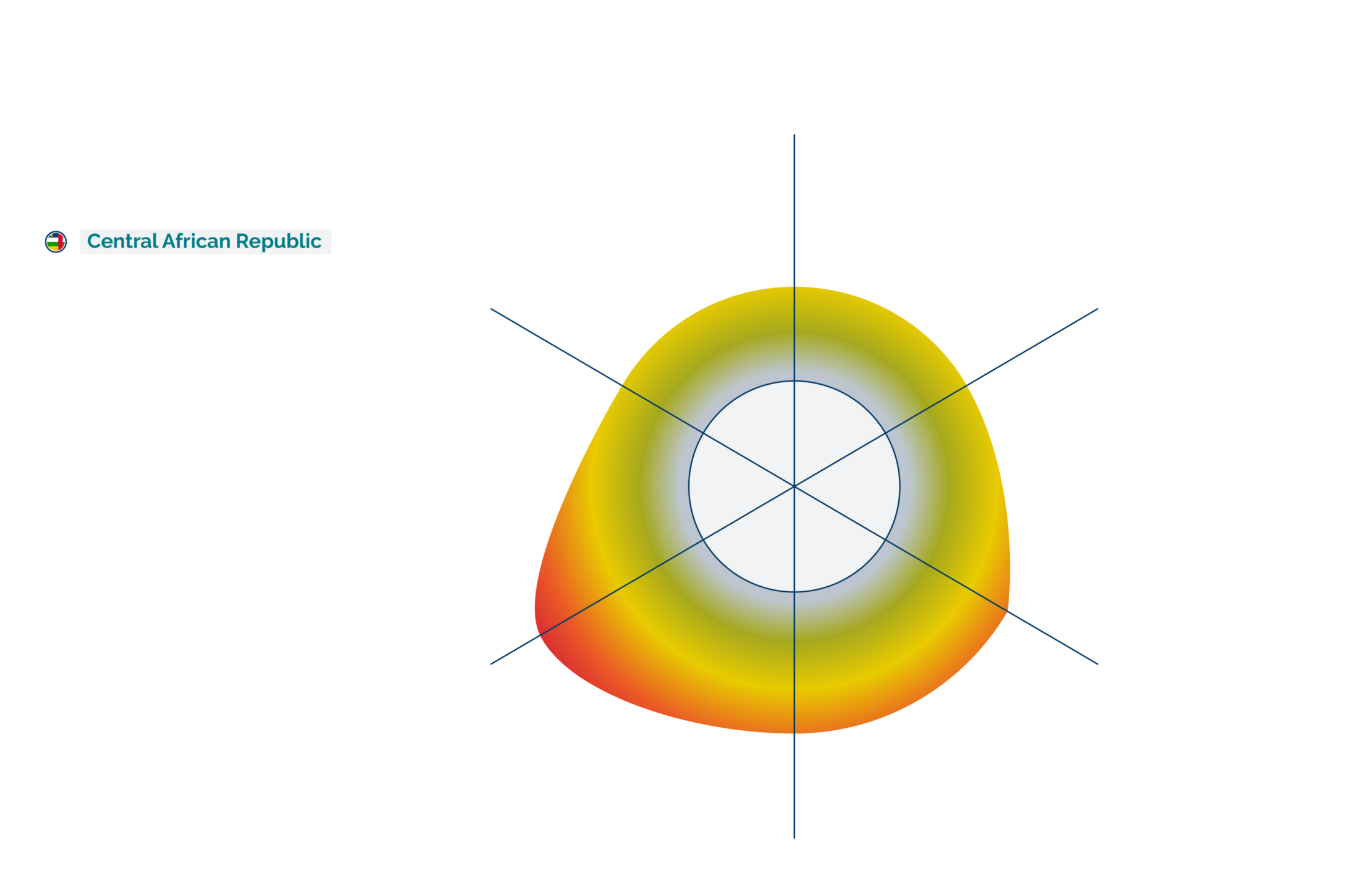

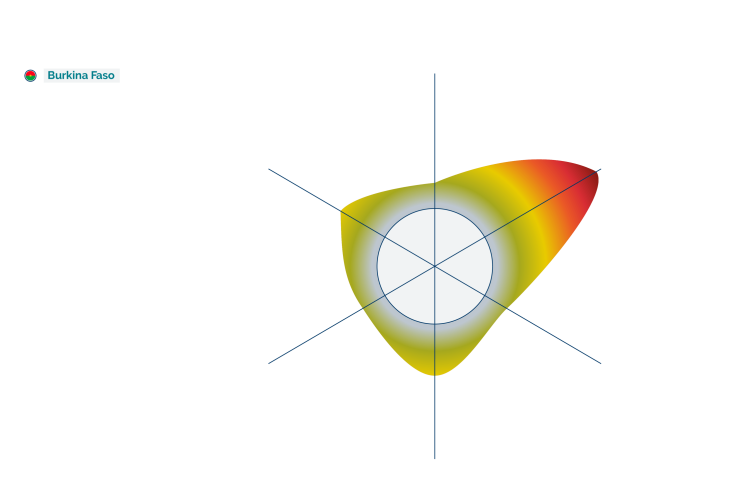

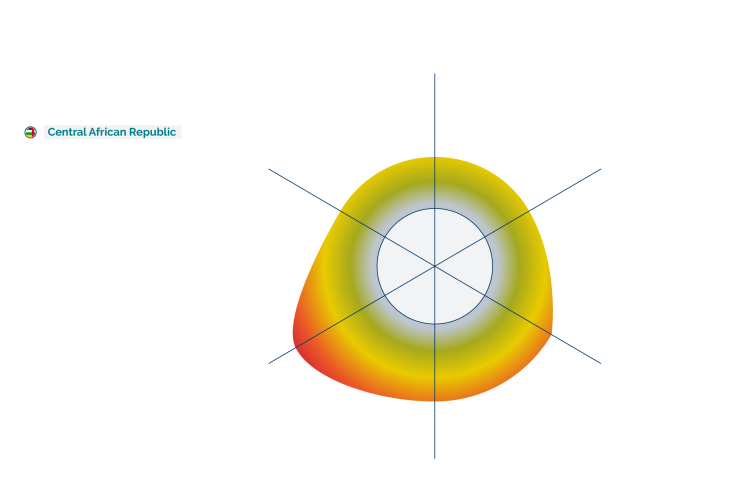

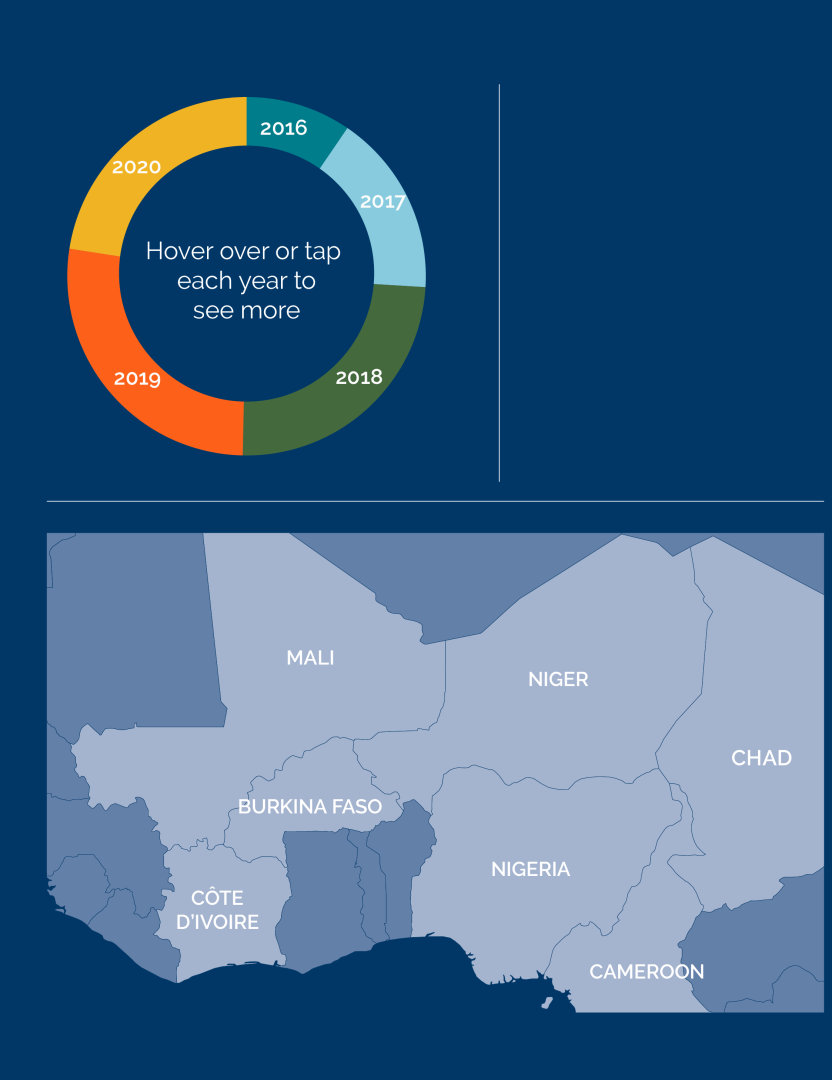

Ongoing inter-communal violence in rural areas of many West African and Sahelian countries is likely to be a key driver of internal displacement in 2021. Data from 2020 indicates that the number of internally displaced people in Burkina Faso doubled to one million in a year, alongside an increase in violence between ethnic communities. The countries at the highest risk of internally displaced people and refugees are Burkina Faso, the CAR, Mali and Nigeria.

Inflation and rising food prices in Nigeria

Price inflation of staple foods such as rice would very probably undermine the living conditions of many millions of people in Nigeria. The Nigerian government’s ability to stave off inflation of the naira is also likely to diminish with low oil prices hitting foreign currency reserves. A government ban on using foreign exchange to import food is also likely to accelerate food price inflation. These pressures will probably have implications for the risk of unrest and riots in major cities such as Abuja, Benin City, Ibadan, Lagos and Port Harcourt.

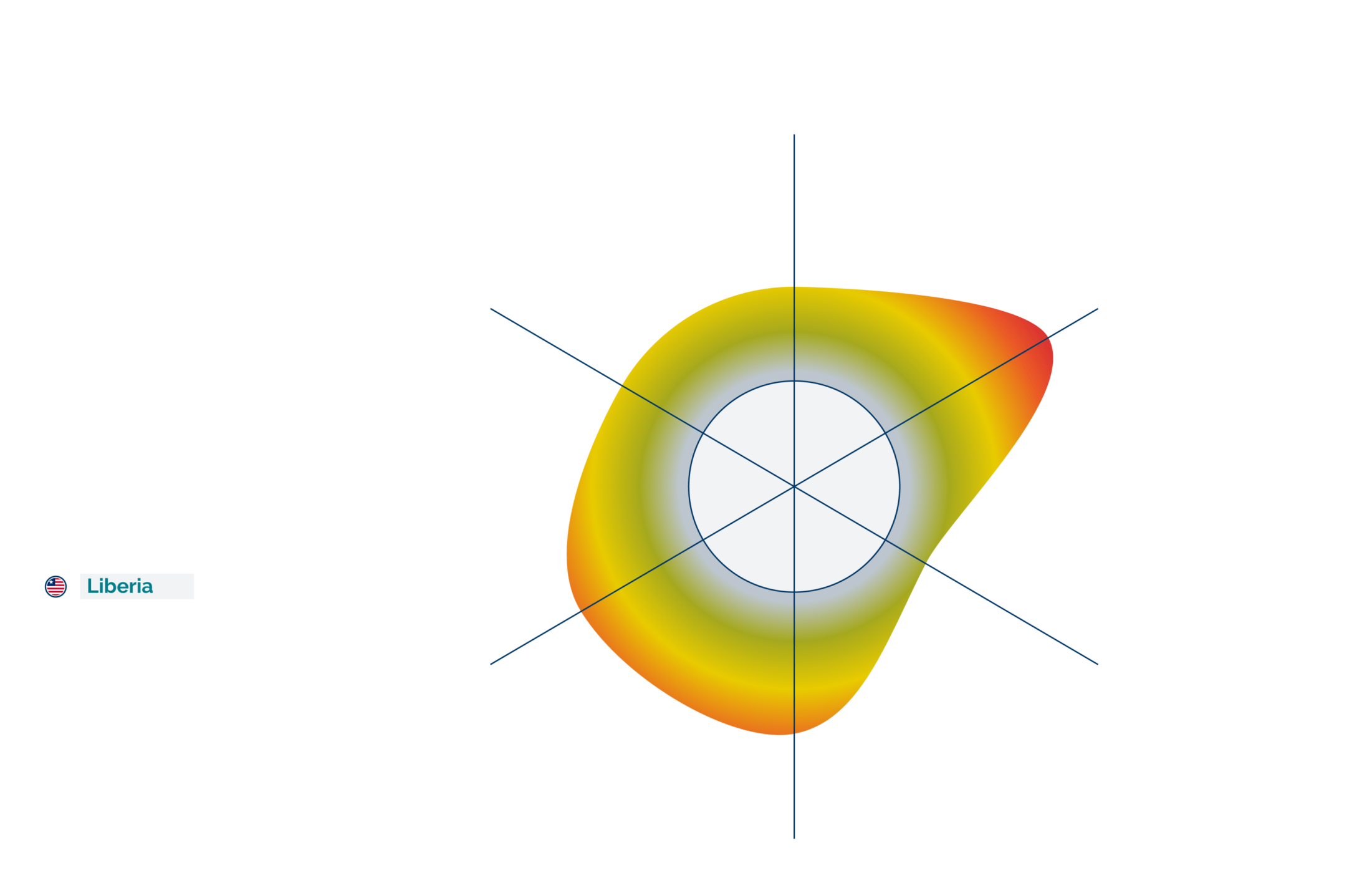

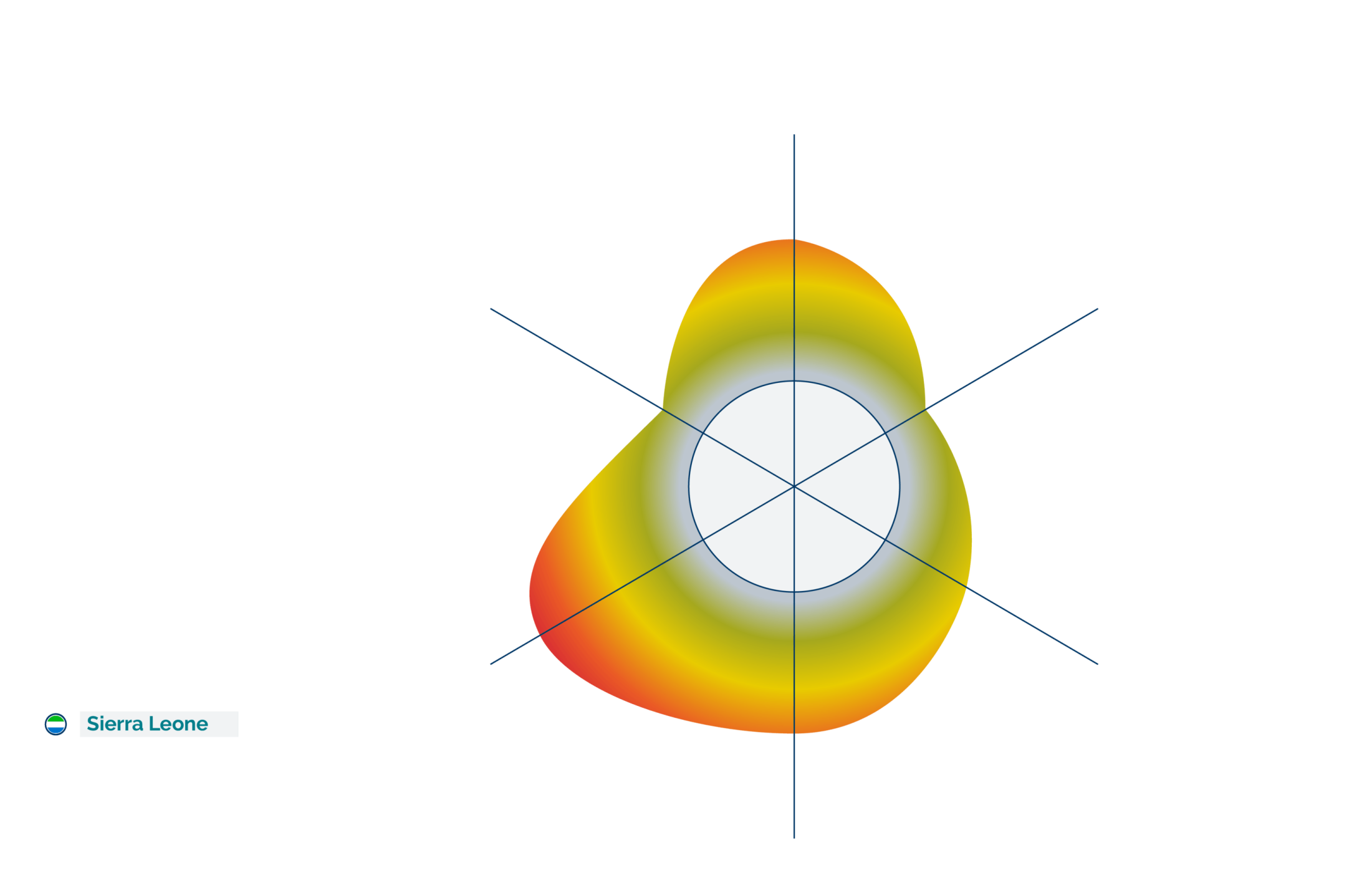

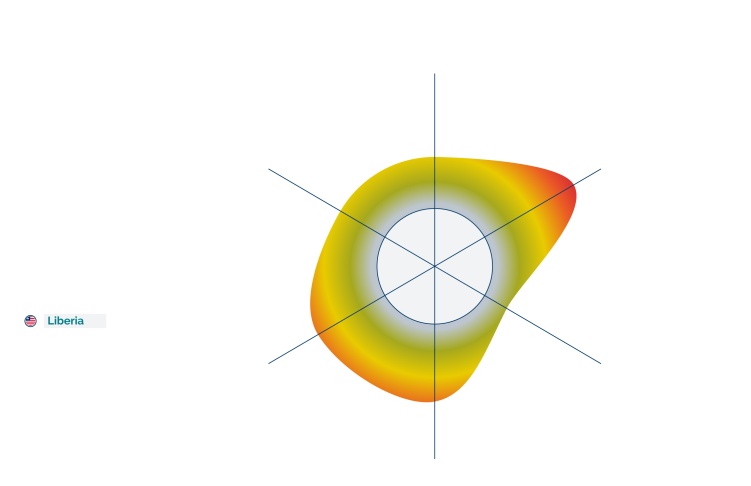

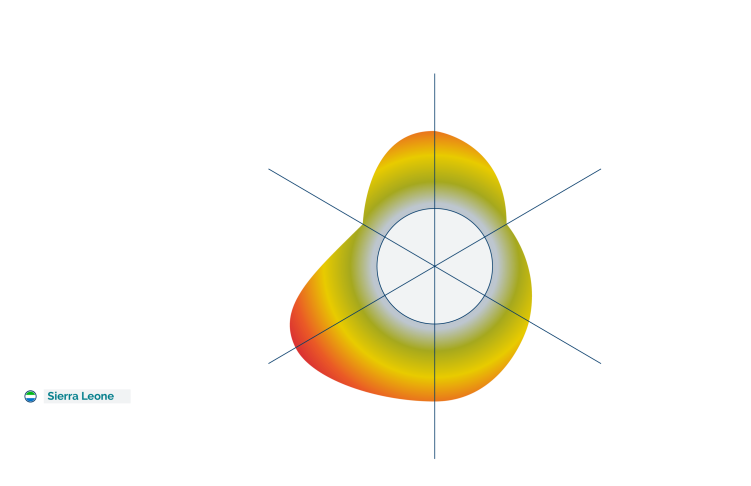

Covid-19 corruption

Evidence, or even allegations, that government officials or other political elites are profiting from the procurement of Covid-19 vaccines or related goods such as PPE would be a flashpoint for anti-government protests in several countries. Based on our understanding of corruption dynamics, as well as socio-economic conditions, this would be most likely in Cameroon, the DRC, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

Images: Thierry Charlier; Ludovic Marin; Romain Chanson; Olympia De Maismont; Alexis Huguet; AFP Contributor/Getty Images

AFRICA

Overall trend: Worsening

CONSISTENT

WORSENING

IMPROVING

Image: Leon Neal/Getty Images

Like all the world, the broader strategic outlook for the region is pegged to the roll-out of effective Covid-19 vaccines or treatments worldwide.

Sub-Saharan Africa had far lower case rates of Covid-19 than the Western hemisphere in 2020, although their economies took big hits. And in 2021, we forecast that one of the biggest strategic risks in the region is the ongoing pandemic suppressing demand for oil and other resources, and strangling revenues that enable governments to stay in power.

The economic fallout of Covid-19 is particularly likely to lay bare deep dysfunction and grievances in Nigeria, where oil revenues have long bailed out poor governance. The country is already in the midst of a chronic security crisis across much of the north. We forecast that in 2021, protests will make the south less stable, and also that there is potential for the whole country to experience a wave of demonstrations that could be unprecedented in how they unify different ethnic, social and

religious groups against the government and political system.

A police brutality scandal in 2020 sparked widespread anger and achieved a rare feat of uniting many Nigerians in common cause under the banner of #EndSARS. A movement mass-protesting against police violence started to widen its demands to end poor governance in Nigeria. Curfews and violence at protests suppressed this, but the potential for a broader social media-enabled protest movement to emerge and challenge the government now has a precedent. Declining revenues mean that the government’s already limited capability to address the myriad grievances of Nigerians will almost certainly erode further

in 2021.

Such unrest is very unlikely to lead to any real political change in Nigeria in 2021. But it would pose new and increased security risks on the ground, further impact the economy and stretch security resources. None of this is positive for the government's capacity to contain terrorism risks in the northeast. We also warn that insecurity in northern Nigeria will further enable Islamist extremist factions in the Lake Chad basin to develop a cross-border land bridge with groups in the Sahel, and vice versa. And more broadly, our security outlook for both the Lake Chad and Sahel areas

are negative.

Other petro-dependent countries – namely Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of Congo – are equally exposed to what is likely to be a persisting weak oil price through 2021. And they will have few options but to cut public spending. The repressive nature of most of these governments means that such cuts would be unlikely to yield any major instability in 2021. But we anticipate a baseline rise in the risks of hardship protests, crime and corruption in all of these countries through the year. And spending cuts would be highly damaging to the fabric of society in the longer term.

While a governance crisis in the Republic of Congo is unlikely, we nevertheless warn that an unsettled period is likely to foreshadow and follow a presidential election at some point in 2021. A date is yet to be set, but we anticipate that the polls will open in the second half of the year when the incumbent, President Denis Sassou Nguesso, will undoubtedly secure yet another term.

Elections in both Benin and The Gambia will probably also bring about an increased risk of instability. Recent crackdowns on the opposition

in Benin will almost certainly feed into a narrative that a presidential poll due there in the first quarter will not be free and fair. The incumbent, Patrice Talon, may well be the only candidate. And we forecast that he will secure a second term at the poll. This will probably trigger protests. And in The Gambia, we also anticipate demonstrations in Banjul and Serekunda if President Adama Barrow announces he will run for a second term. These would be unlikely to be particularly large or long-lasting, however.

The outlook is more positive for those countries that profit from surging demand in the few commodities that offer safe havens amid the pandemic. Continued demand for gold and other goods are likely to leave both Ghana and Senegal fairly well placed economically in 2021. While the threat of terrorism is likely to be high in Senegal, neither country has any probable flashpoints that we assess will lead to political upheaval in the coming year. Revenues from cobalt exports will probably sustain an uneasy status quo between President Tshisekedi and the former president, Joseph Kabila in the DRC. The main risk of instability will be as politicking continues to build ahead of a presidential election

in 2023.

Cote d’Ivoire should also enjoy similar revenues and stability prospects. But its fortunes in 2021 will strongly depend on the extent to which President Ouattara can find a way to placate the opposition which does not recognise his third term. Further talks and meditation are likely in the first half of the year. But unless the opposition formally accepts Mr Ouattarra’s third term or there is some kind of power sharing agreement, we would expect pockets of ethnic violence to breakout and become more frequent. This is an avoidable conflict but it has every potential to be the most disruptive crisis in the region in 2021.

Image: Arsene Mpiana/Getty Images

Declining revenues mean that the government’s already limited capability to address the myriad grievances of Nigerians will almost certainly erode further in 2021.

Image: Pius Utomi Ekpei/Getty Images

It is likely that militants linked to Al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM will attempt to expand their operational reach into Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal in 2021. Insurgents mounted an attack in the northern border area of Côte d’Ivoire for the first time in 2020. We anticipate more. We also assess that there is a reasonable chance that militants will try to launch a first attack in border areas of Senegal, and also potentially a more high-profile attack in Dakar or Abidjan targeting places popular with foreigners, such as hotels.

Spread of terrorism into Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal

Forecasts

An insurgency by Anglophone separatists in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon is likely to continue throughout 2021. There will probably be increased pressure on the government to engage with militants to seek a political solution to the conflict. It is possible that moderate separatist factions would participate in talks. But the disparate nature and demands of Anglophone groups more broadly means that any deal would be highly unlikely to bring about an end to violence in the two regions.

Continuing conflict in Cameroon

Guinea is likely to move on from several years of political crisis in 2021, following President Alpha Conde’s victory at an election in late-2020. Although the opposition has emerged from the crisis more divided than before it, we anticipate that activists will try to mobilise people over a range of other issues. These include corruption, poor government services, socio-economic conditions and to demand electoral or constitutional reforms. This will probably lead to disruptive and violent protests in Conakry through 2021, albeit less frequently than in previous years.

Improving outlook in Guinea

Source: Risk Advisory TerrorismTracker

Outliers

Re-emergence of insurgency in the Republic of Congo

Monitoring Points

Displacement in the Sahel and Lake Chad

Inflation and rising food prices in Nigeria

Ongoing inter-communal violence in rural areas of many West African and Sahelian countries is likely to be a key driver of internal displacement in 2021. Data from 2020 indicates that the number of internally displaced people in Burkina Faso doubled to one million in a year, alongside an increase in violence between ethnic communities. The countries at the highest risk of internally displaced people and refugees are Burkina Faso, the CAR, Mali and Nigeria.

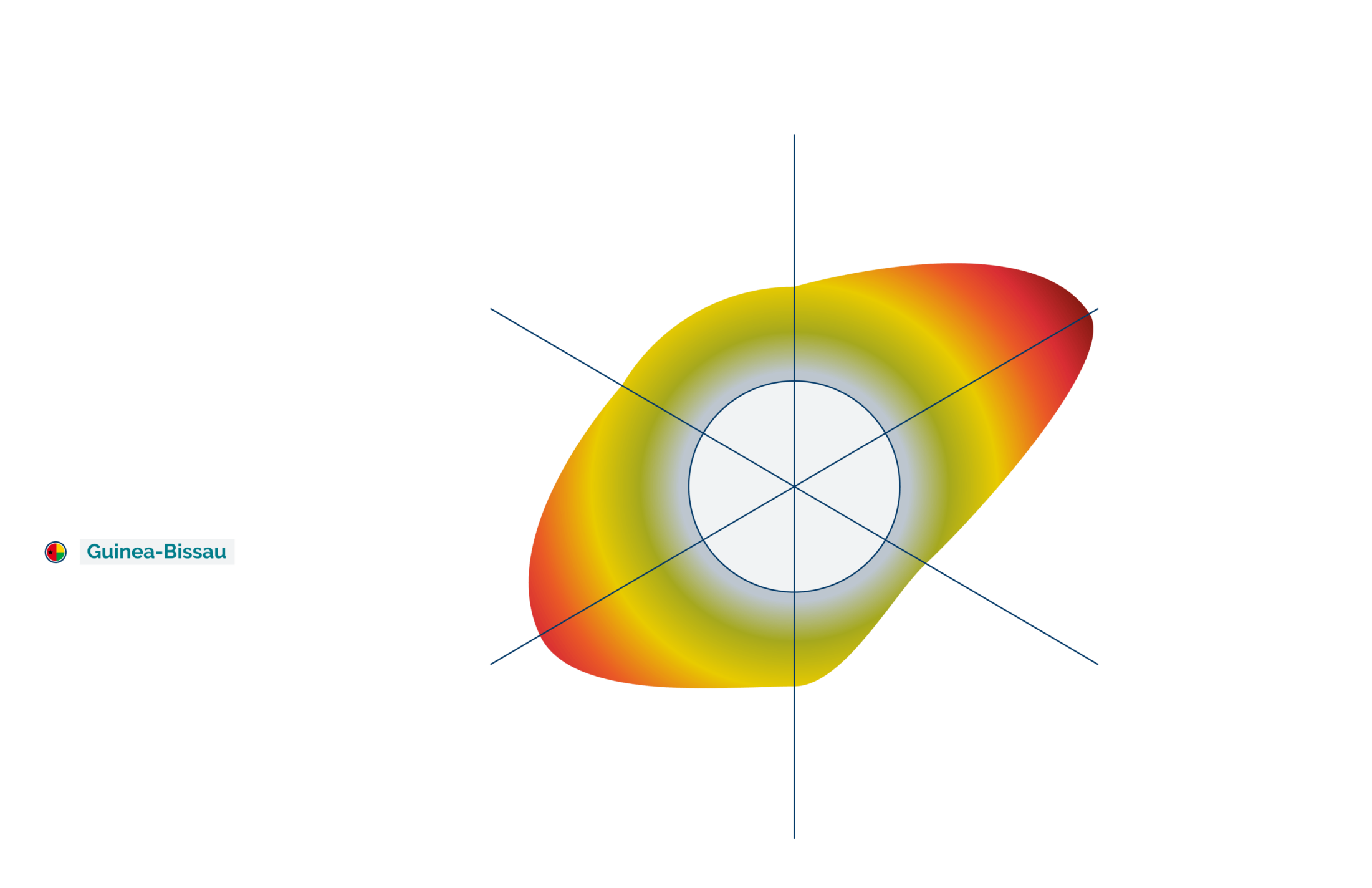

Covid-19 corruption

Evidence, or even allegations, that government officials or other political elites are profiting from the procurement of Covid-19 vaccines or related goods such as PPE would be a flashpoint for anti-government protests in several countries. Based on our understanding of corruption dynamics, as well as socio-economic conditions, this would be most likely in Cameroon, the DRC, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

Price inflation of staple foods such as rice would very probably undermine the living conditions of many millions of people in Nigeria. The Nigerian government’s ability to stave off inflation of the naira is also likely to diminish with low oil prices hitting foreign currency reserves. A government ban on using foreign exchange to import food is also likely to accelerate food price inflation. These pressures will probably have implications for the risk of unrest and riots in major cities such as Abuja, Benin City, Ibadan, Lagos and Port Harcourt.

Images: Thierry Charlier; Ludovic Marin; Romain Chanson; Olympia De Maismont; Alexis Huguet; AFP Contributor/Getty Images