With further warming, climate change risks will become more complex and so harder to manage. Multiple climatic and non-climatic risk drivers will interact. Climate-driven food insecurity and supply instability, for example, are projected to worsen as the planet warms. Those will interact with non-climatic risk drivers such as competition for land and pandemics.

..and so risks accumulate

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – with high confidence – that sectors, such as agriculture, forestry, fishery, energy, and tourism have already been damaged economically by climate change. The destruction of homes and infrastructure, loss of property and income, and decreasing health and food security also have adverse effects on gender and social equity.

Biodiversity and ecosystems

Cities, settlements and infrastructure

Health and well-being

Water availability and food production

Key categories

At COP29, richer countries pledged $300 billion a year to help poorer countries fight climate change. The record-breaking sum was finally announced in Baku at 0300hrs local time on 24 November – after talks had run 33 hours late. But it fell far short of the $1.3 trillion developing countries had pushed for. While world leaders struggle to come to terms with the skewed dynamic of who causes and who endures climate change, there is widespread agreement that it has already reduced food, energy and water security.

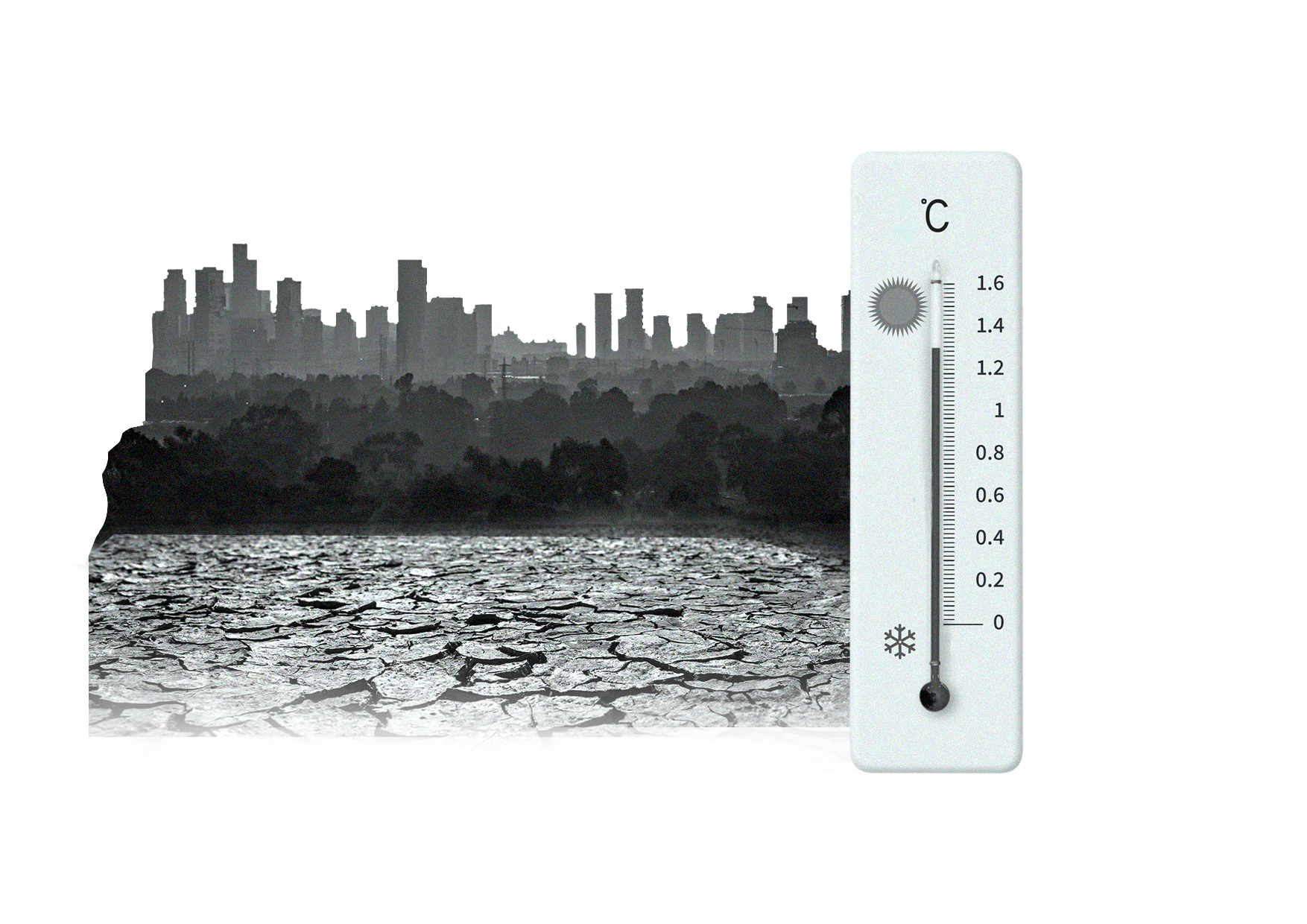

2024 has been confirmed by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) to be the warmest year on record globally, and the first calendar year that the average global temperature exceeded 1.5°C above its pre-industrial level.

The effects of climate change such as extreme weather events, rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns are socio-economic.

Climate change is a societal problem…

For now, warming continues…

For now, greenhouse gas emissions will continue to warm the globe. This will affect all major climate system components, not least the global water cycle, its variability, and global monsoon precipitation, leading to very wet and very dry weather and climate events and seasons. Compound heatwaves and droughts are projected to become more frequent, leading to concurrent events across multiple locations.

Western militaries and defence planners, national security think tanks and intelligence agencies, the UN, IMF and World Bank, state development agencies, humanitarian and development NGOs, environmental campaigners, mainstream liberal media and authoritarian governments in the Global South:

all have in one way or another, and for one reason or another, argued that climate change has sweeping implications for conflict and security.

what happened in Darfur was a ‘traditional conflict’ rooted in ‘frictions between the shepherds and the farmers’ that ‘increased because of climate change and the dry weather’.

the main cause of the conflict in Darfur was desertification and drought.

the Darfur war ‘began as an ecological crisis’, and even described it as the world’s first ‘climate change conflict’. This was an attempt to mollify Sudan at a time when he needed its cooperation over the establishment of a peacekeeping mission.

Ban Ki-Moon, then secretary-general of the United Nations, asserted that

The Sudanese government at the UN Security Council said

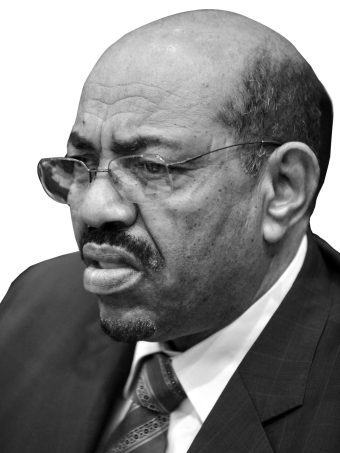

Then-president Omar Al-Bashir claimed that

This reframing of the conflict distracts from and hides the political causes of the conflict: the government’s disregard for the western region and its non-Arab population.

For militaries and defence planners, this serves to make them more relevant. If climate change is considered a security threat, it would make sense to spend more money on the military. National security think tanks and intelligence agencies also stand to secure more funding.

For authoritarian regimes and elites, climate change can be a scapegoat. Instead of taking responsibility for socio-economic issues or bad policies, they can blame climate change. This also fits into the wider – and not unfounded – discourse of holding the Global North responsible.

What do people say about climate change and conflict?

If climate change has negative socio-economic impacts, then surely it has significant consequences for (in)security.

In short:

increases the risk of armed conflict.

or migration,

through resource competition

Climate change,

Climate change,

and civil and political conflict

This interacts with existing patterns of poverty and fragility.

migration and displacement,

economic and social vulnerability

Those, in turn feed resource competition,

exacerbating resource pressures and scarcities

causes both short-term environmental shocks and long-term trends

Usually, the argument goes like this:

How does climate change cause conflict?

See here for the 7 commonly suggested pathways linking climate change to violent conflict.

Climate change mitigation can also negatively affect societies, in particular vulnerable groups, and strengthen the position of those in power.

Compared with the noise on climate change as a cause of conflict, there is much less talk of the potential harms of some climate actions to human security. And that is crucial, given the way that some authoritarian regimes have used the climate-conflict link to deflect blame and implement extraordinary measures. Those may in turn lead to conflict.

That is most likely to happen in countries where there are high climatic and political risks.

Drawing on Dragonfly risk ratings, this graphic shows political and climatic risk scores for each country, grouped by region. Dragonfly’s climatic risk rating takes into account historical and current data on floods, droughts, cyclones and air quality. The political risk rating is a composite score of the Civil Conflict, Civil Unrest, Crisis Risk, Regime Instability, Security & Safety Risk, and Terrorism Risk Dragonfly ratings.

The argument that climate change causes conflict also supports the need for measures aimed at climate change mitigation and adaptation. But limiting warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, as enshrined in the Paris Agreement, will require substantial interventions. Those far exceed what has been done to date.

Climate change mitigation measures are not all good

What can be done to mitigate these risks?

Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, Haiti, Philippines, Bangladesh, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, and Ethiopia score highest when considering political and climatic risks, making them particularly vulnerable to negative effects of climate mitigation measures.

development

Let’s consider in depth two mitigation strategies; hydraulic development and reforestation/green energy projects.

Climate action has the potential to cause insecurity in different ways. For instance, the rapid decarbonisation of energy systems affects demand and rents of high-market-value resources, such as oil and gas. This can destabilise resource-dependent states like Iraq or Venezuela.

Those climate actions can lead to specific security risks

A common response by political elites to water scarcity is to construct large dams, securing sizeable water reservoirs. Another approach taken to combat climate change is planting trees, a lot of them. This seems sensible, as (re)forestation, at least in theory, removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

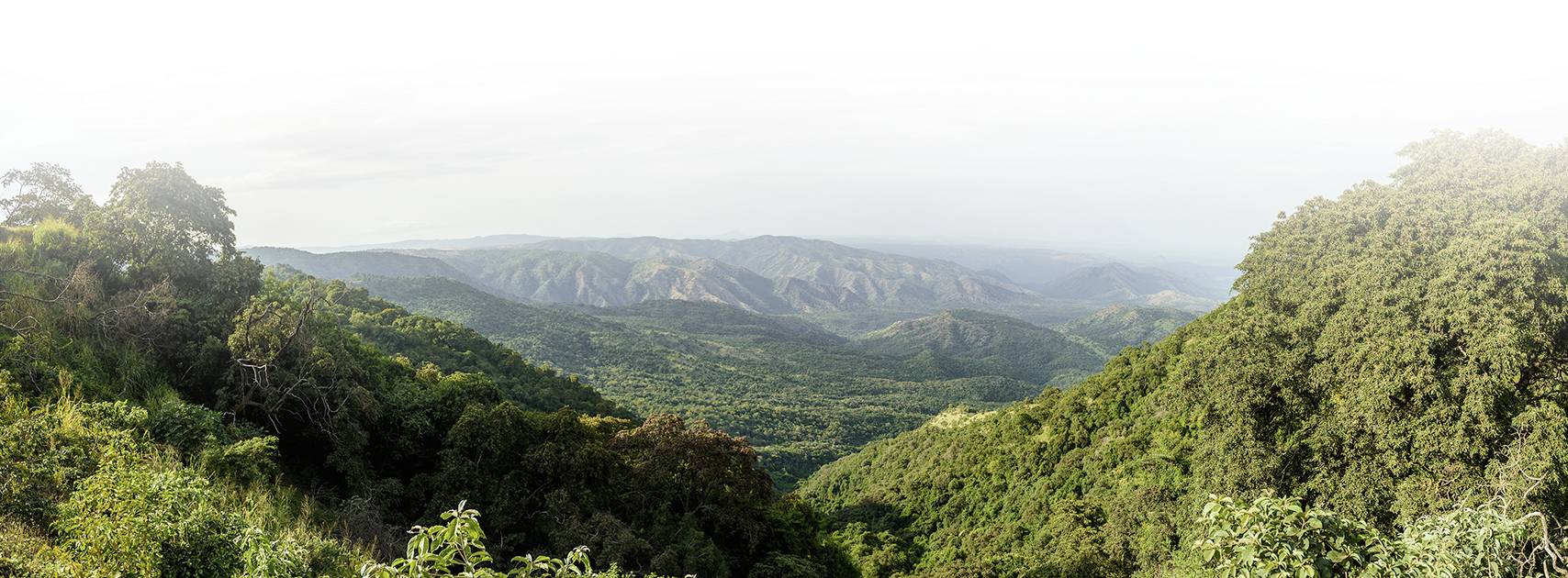

However large-scale forestation projects can be detrimental to local communities and biodiversity. Their opponents call this ‘Green-grabbing’.

The need to limit climate change and mitigate its effects is urgent. This is generally agreed upon in academic and policy circles. However, as climate change is used to justify extreme measures, such as constructing megadams and buying up vast areas of land, by international organisations and national governments, it is crucial to examine these actions and their potential side effects more closely.

For example, a new dam intended to reduce water scarcity and prevent conflict may actually increase those risks by displacing communities and damaging the environment. Similarly, large areas of land purchased by companies to plant forests might aim to offset CO2 emissions but could end up displacing local communities and having little positive impact on the environment.

These interventions often interact with existing power dynamics, meaning that elites can further marginalise communities. This can lead to protests and even armed violence. And so for organisations looking to analyse how climate change might affect security risks, it will be important for them to scrutinise not just the effects of climate change itself but also those measures taken to counter it.

Wrapping up

+44 20 3653 0010

www.dragonflyintelligence.com

Sierra Quebec Bravo

77 Marsh Wall,

Canary Wharf

London

E14 9SH

Get in touch

Sources:

Carlos Quesada and Juan Pablo Guerrero, Green Grabbing in the Galilea Forest?, Dejusticia, 25 July 2024

Cardenas, R., Green multiculturalism: articulations of ethnic and environmental politics in a Colombian ‘black community’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 19 April 2012

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S)

Dragonfly

Filer, C., Why green grabs don't work in Papua New Guinea, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 19 April 2012

Mokuwa, E. et al., Peasant grievance and insurgency in Sierra Leone: Judicial serfdom as a driver of conflict, African Affairs, July 2011

Increasing Pressure for Land: Implications for Rural Livelihoods and Development Actors - A Case Study in Sierra Leone, Green Scenery, October 2012

Klingler, M. et al., Large-scale green grabbing for wind and solar photovoltaic development in Brazil, Nature Sustainability, 13 May 2024

Laura Roper, Human Rights Pulse, 16 November 2021

Maria Luisa Mendonca, Phenomenal World, 28 May 2022

Rincón Barajas, J. et al., Large-scale acquisitions of communal land in the Global South: Assessing the risks and formulating policy recommendations, Land Use Policy, April 2024

Selby, J., Daoust G. & Hoffmann C., Divided Environments: An International Political Ecology of Climate Change, Water and Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

West, T et al., Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation, Science, 24 August 2023

Image Credits:

Images from Getty Images include works by Sean Gallup / Staff, SIMON MAINA / Stringer, FRANCOIS GUILLOT / Staff, Alissa Everett / Contributor, SIMON MAINA / Stringer, and Andrea Ricordi, Italy, (Royalty-Free). Images from Adobe Stock are by piyaset, Tomas Ragina, Eli Mordechai, AA+W, Stocksvids, luisapuccini, Fernando, Mati Kose, Olga, ivanbruno, New Africa, lisur, Joaquin Corbalan, domingostalon, ReeseArcurs/peopleimages.com, namotrips, Stockr, MaxSafaniuk, sihasakprachum, and Ajdin Kamber. Creative Commons-licensed images from Wikimedia Commons and Flickr include "Official portrait of Rt Hon Margaret Beckett MP crop 2" by Richard Townshend (CC BY 3.0), "Ban Ki-moon February 2016" by Chatham House (CC BY 2.0), "Extinction Rebellion. Banner 'Rebel for life'" by Julia Hawkins (CC BY 2.0), "Jisr az-Zarqa from southwest" by Ori~ (CC BY), "Flickr do Palácio do Planalto" by Isac Nóbrega/PR (CC BY 2.0), and an image by Sean Wu from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD/ENB) (CC BY 4.0).

Analyst: Jim Kerres

Design: Syennie Valeria

Editor: Hannah Poppy

Contributors: Clarice Lam, Lindsay Lombard, Sudhanshu Agarwal

First published in December 2024 by Dragonfly Eye Ltd

SQB, Canary Wharf, London, E14 9SH, United Kingdom

© 2024 Dragonfly Eye Ltd

Dragonfly is a private intelligence service to professionals who guide decision-making in the world’s leading organisations. From the highest risk environments to the boardroom, we enable our clients to make confident decisions and put them ahead of security and crisis risks.

www.dragonflyintelligence.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be printed or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.