High-Risk Maritime Zones

Coastal countries are most at risk of shadow fleet-related incidents. This includes busy maritime routes, such as Kattegat, Gibraltar and the English Channel. In last year's report, Greenpeace warned that 171 shadow fleet tankers in the last two years passed through the Fehmarn Belt (leading to Kattegat) which endangers Germany’s Baltic coast with oil spills and traffic disruptions due to a lack of appropriate insurance.

According to Lloyd's list analysis, there are multiple hotspots for bunkering Russian oil across European waters, including the coasts of Gotland (Sweden), the Laconian Gulf, Lesbos and Chios (Greece) Romania and around Malta. In case of a spill (e.g. during the ship-to-ship transfer of oil), it is very likely that the burden of cleanup would fall on the coastal country’s budget.

The Kyiv School of Economics estimates the clean-up cost from a single tanker at $859 million - $1.6 billion. The oil spills affecting coastal states’ shores are meant to be covered by the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (IOPC). But shadow tanker owners do not contribute to it, so this fund is likely to run dry quickly in case of an accident.

The Russian shadow fleet is almost certain to grow in size and pose a high risk to maritime traffic in Europe in 2025. Since the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions, Russia has been circumventing these by using the so-called shadow fleet. According to shipbroker BRS, the fleet involves 8.5% of all oil tankers, growing from 200 to approximately 787 ships in the last three years.

Shadow fleet poses several risks to maritime routes, ports, and coastal states. These include disruptions to sea traffic, damage to critical infrastructure, and espionage, especially in the Baltic, North, and Mediterranean Seas. Coastal countries along Russian oil shipping routes, including Norway, Denmark, Finland, the UK, and Sweden, are also exposed to related risks.

Russia is increasingly reliant on the shadow fleet to circumvent sanctions, raising the risk associated with its usage

These could include oil spillages, ship abandonment, disruption of maritime routes, espionage and damage to critical infrastructure

Coastal countries along Russian oil shipping routes such as Norway, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, UK and Greece are at the highest risk of being affected by a shadow fleet-related accident in 2025

28 February 2013

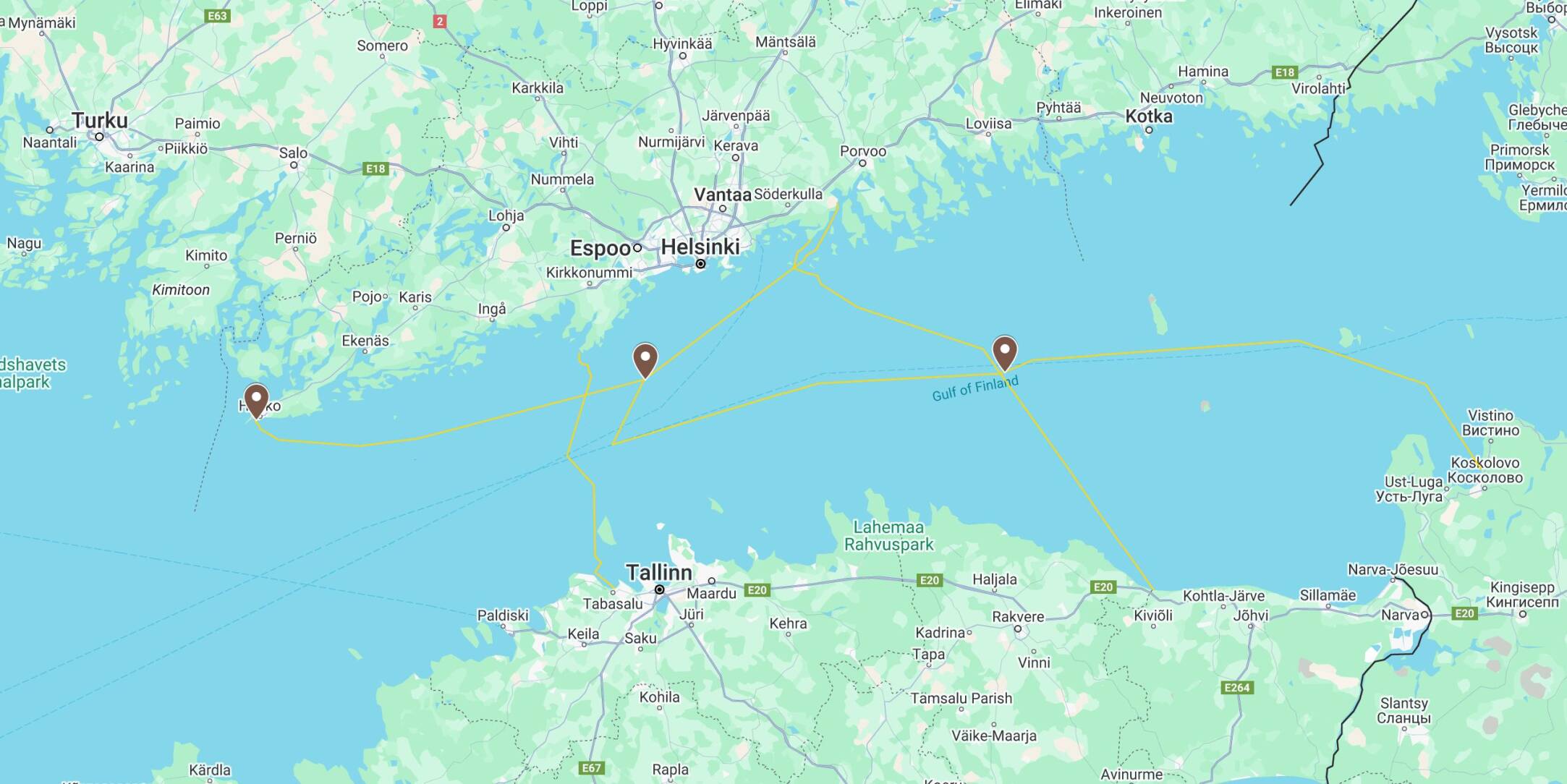

Eagle-S held in custody, with the crew facing charges of aggravated vandalism and interference with telecommunications

25 December, 2140hrs

Turva met with the Eagle-S 20km from Porkkala and escorted it the following day to an anchorage point in Sköldvik bay

Around 1830 hrs, the Finnish Coast Guard vessel Turva ordered Eagle-S to enter Finnish territorial waters

Within the next 6 hours, Eagle S damaged five more telecom cables with the anchor, heading towards Estlink-1

25 December 2012, 1226hrs

Fingrid reports a power outage as Eagle S dropped the anchor and dragged it over Estlink-2 energy interconnector

The Russian shadow fleet sustains a high risk of sabotage and espionage. Incidents of damage to subsea infrastructure are orchestrated to occur as random, but are seemingly a part of Moscow’s bigger hybrid warfare campaign. In the last four years, we have recorded eight cases of damage caused to subsea cables, spread across the North and the Baltic Seas. For instance, in December, the Eagle-S tanker not only damaged subsea infrastructure in the Gulf of Finland but also carried espionage equipment onboard according to Finnish authorities.

Damage to subsea infrastructure can affect regional internet access and energy supply. For instance, the energy interconnector damaged last year in the Gulf of Finland by the Eagle-S tanker will take several months to repair, undermining energy security. More than 200 Russian vessels have been spotted loitering over critical subsea infrastructure across the North Sea since 2014, according to investigative journalists. Some of these were affiliated with Russian ‘fishing’ and cargo vessels. Such incidents are likely to continue in 2025 (for more details see our report XXX).

The second category relates to accidents caused by these ships. The average age of a tanker in the shadow fleet is over 15 years, out of 20 years of a typical oil carrier lifespan. This results in maintenance problems, such as engine failures leading to collisions or loss of manoeuvrability. For instance, in May 2023, the Cook Islands registered 18-year-old shadow fleet tanker, the Canis Power, loaded with 340,000 barrels of Russian oil products, which lost engine power while passing through the Danish Straits and almost ran aground.

The vessel drifted for six hours, before it dropped the anchor for repairs, blocking the traffic in the strait

11 March 2023

Canis Power tanker lost power and nearly ran aground, 1,500 meters from the coast, when passing the Great Belt Strait

Shadow fleet tankers pose a risk to maritime traffic due to crew incompetence and potential ship abandonment in case of accident. Coastal countries or hosting ports must cover any costs related to these ships. For example, the Russian tanker Khatanga failed an inspection and was abandoned in the port of Gdynia, Poland, eight years ago. A court recently ordered its removal, and the port administration will fully cover the costs.

As these tankers do not have a proper insurance, they also do not have to adhere to business standards for crew qualifications, resulting in ‘lack of seamanship’. This was named by Swedish authorities as a potential cause of damage to a subsea cable near Gotland in January this year. One in five shadow vessels crossing without the Danish Kattegat straits refuse to use pilotage in treacherous waters, risking an incident and major traffic disruption on a key maritime route.

Due to sanctions, these vessels often lack sufficient insurance. Thus, in case of an accident, the chances of any claims from the policy are minimal, leaving all costs of clean-up, removal or scraping these ships on the receiving port or coastal country. In January 2025, an 18-year-old Eventin tanker with 99,000 tonnes of Russian oil had to be towed away by German authorities due to engine failure.

12 January 0625hrs:

Eventin reaches the anchorage point, where it remains up until today, kept in place by commercial tugs

11 January 0150hrs:

Tug convoy moves Eventin to anchorage point east of Sassnitz port

23:38hrs:

additional gus VB Luca and VB Bremen establish towing line with Eventin, holding it in place

1532hrs:

Bremen fighter establishes towing connection with Eventin

1357hrs:

Germany’s maritime accident command dispatches Bremen Fighter and VB Luca tugs to the tanker, with additional tug Baltic and rescue vessel Arkona on the way from the port in Rostock

10 January 2025, 1230hrs: Eventin tanker sailing from Ust-Luga to Port Said suddenly lost engine power and drifted off the coast of Germany near Cape Arkona amongst winds reaching 7/10 in Beaufort scale

1 March:

Vladimir Latyshev is apprehended by Saint-Malo Customs, as it was added to the sanctions list a day before

28 February 2022:

Vladimir Latyshev cargo ship arrives to Saint-Malo delivering magnesia

The third category is oil spills associated with circumventing sanctions. Shadow fleet vessels are likely to be engaged in ship-to-ship transfers of oil (bunkering), often using unfit small river tankers or cargo ships on the open sea to pump low-quality heavy oil (mazut) to a bigger carrier to avoid sanctions. Such operations, done by inexperienced crew on an old ship, can lead to oil spills. In December, two river-class tankers sank in the Kerch Strait and spilt up to 5,00 tonnes of heavy oil across the Black Sea, reportedly on the way to pump oil over to a bigger oil tanker.

Oil spills and collisions due to sanctions circumvention

17 December:

State of Emergency announced in the area due to Mazut spillage and first spills reaching shores

15 December, circa 1020hrs: Volgoneft-239 sends SOS signal as well and ran aground 80m from the shore

15 December, circa 1000hrs: Volgoneft-212 sends SOS signal caught in a storm

15 December, 0840hrs:

Volgoneft-212 breaks in half during a 7/10 Beaufort scale winds

November-December 2024: Volgoneft-212 and 239, both river-class tankers, sail towards a bunkering hotspot outside the port of Kavkaz to meet the FIRN tanker

The shadow fleet is likely to continue causing maritime disruption due to the limited capabilities of coastal states to react. In December 2024, the Baltic countries agreed on a ‘disrupt and deter’ approach to tackle shadow fleets. This includes demanding proof of insurance from all units associated with the shadow fleet and, in some cases, inspecting the vessels or straight out banning them. But these measures are very likely to be limited by international maritime law, allowing states to detain shadow fleet tankers only within their territorial waters (12nm), as vessels can reject calls to enter these waters even if they are within the country’s exclusive economic zone (200nm).

Mitigation measures