Image: Getty Images (DAVID MCNEW / Contributor)

Still, there are significant gaps that will require new rules. These include shortfalls in understanding (including legislators’ knowledge of future developments) and data, let alone guidance on ethical questions like, ‘who should bear criminal responsibility for criminal acts promulgated by Gen AI?’. It is likely to take at least a decade to begin to address these. This is because in the UK, US and other common law countries the answers will be determined in lengthy court battles. Legislation is unlikely to be much faster; the Canadian AIDA has only passed two of five legislative hurdles since June 2022.

Trade-bloc-based rules are also likely to take years to enact and roll out. The EU is moving faster on the AI Act than the decade it took to enact GDPR; the European parliament aspires to have the legislation approved by late 2023. But there is much uncertainty around implementation. And given the global nature of trade and labour markets, EU rules will only be part of the puzzle. It will also be important for businesses to monitor the nature of rules that other major trade bodies like the World Trade Organisation (WTO) adopt.

Image: Getty Images (FREDERICK FLORIN / Contributor)

The extent to which new rules seek to protect jobs will no doubt be influenced by the effectiveness of unions, other influence and advocacy groups and leftist parties in doing so.

The current geopolitical context – specifically US-China competition – means that the rules these bodies promulgate will create further competition. That is also because it is in the interest of Western-backed companies driving many of these technological advances to ensure that the regulations protect their commercial advantage. That would in turn pressure countries that fall on the periphery of existing alliances and trade pacts to align with the likes of the EU. This would also intensify a sense of antagonism and isolation from China and its allies.

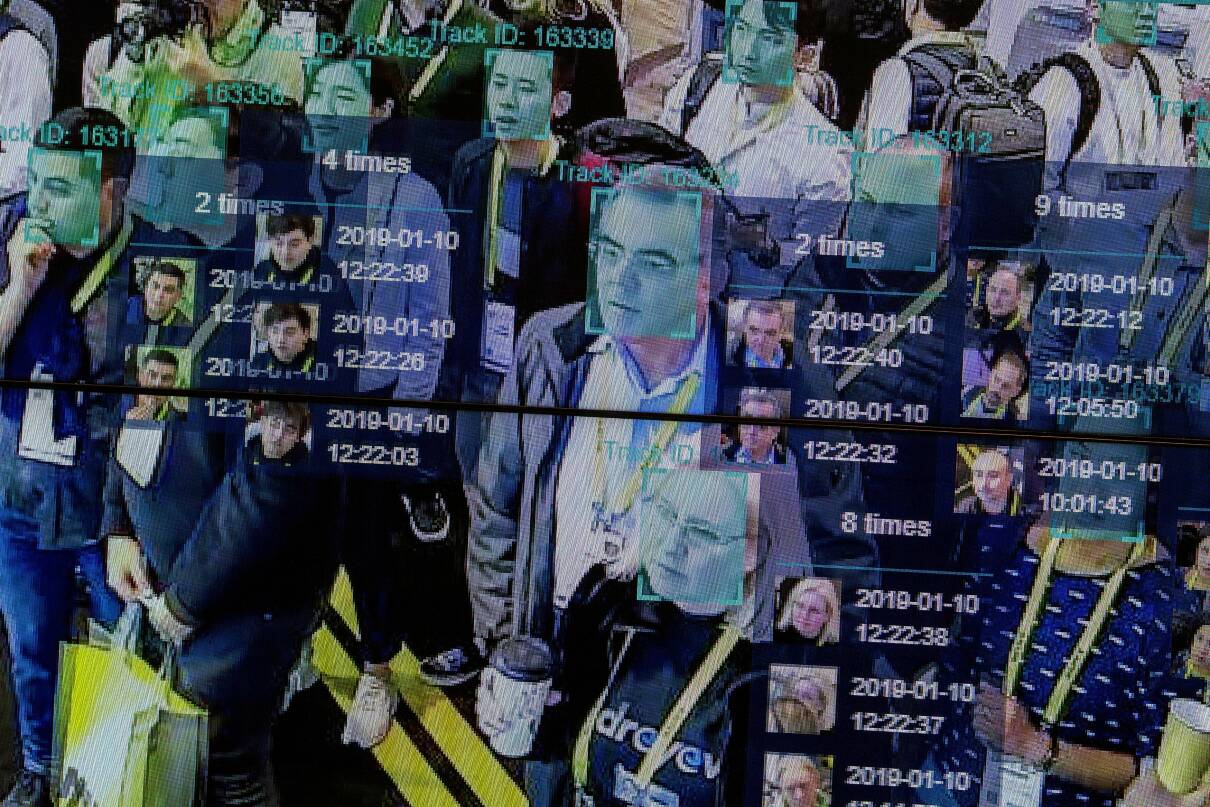

Domestic politics too will determine the speed and strength of regulation. The Dutch DPA was able to muscle into AI issues because of a high-profile scandal stemming from the discriminatory use of algorithms. Ahead of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games the French regulator is scrutinising AI-augmented CCTV. The extent to which new rules seek to protect jobs will no doubt be influenced by the effectiveness of unions, other influence and advocacy groups and leftist parties. Probable consequences are likely to include internal pressure to deploy teams handling new technologies in places with more permissive regulation but that are more exposed to other risks like weak governance and instability.

New rules are no less likely to restrain criminal organisations and other malign actors than old rules. Nor will unscrupulous and disruptive competitors (whether in business, development or politics) become more likely to hold off as a result of regulation. But the fundamentals for security teams to ensure the resilience of their businesses in the face of all these changes are themselves unchanged; they must be able to rapidly identify, adapt to and robustly mitigate emerging risks while keeping an eye on the horizon to anticipate those that are yet to emerge.

AI technologies and their applications do not operate in an unregulated vacuum. Existing labour laws, controls on the transfer of personal data and rules for commercial competition all apply. New rules and controls are likely to come into place through 2024. Canada, for example, is in the process of introducing an Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) that it says will prevent fraud. The Netherlands’ powerful Dutch Data Protection Authority (DPA) began to coordinate with other agencies on AI-related issues in early 2023.

The actions that governments and international bodies take (or not) to regulate generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) over the next five to ten years will be key in determining the extent to which businesses and other organisations can harness the power of these technologies or succumb to them and the risks they create. In other words, regulation will determine resilience, but it will also have the potential to intensify geopolitical fault lines. And the nature of such regulation will also determine more prosaic questions that range from ‘how safe are our people and our assets?’ to ‘which video surveillance provider can we use?’.

Following the AI Innovation Curve