If strategic risk forecasting does not sit at the centre of supply chain strategy and planning, then resilience may prove both costly and elusive.

Image: Getty Images (Kevin Frayer / Stringer)

Global supply chain conditions have mostly rebounded from the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Data compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows that supply chain stressors have largely fallen since their peak in December 2021. Product shortages are easing, delivery times have shortened, port congestion has normalised somewhat and global inventory levels are being restored. But the geopolitical, cyber and environmental risks we forecast in this Strategic Outlook mean that building resilience in complex supply chains will remain an ongoing and urgent task.

Most organisations are still struggling with significant unpredictability concerning the availability and cost of industrial inputs. Supply disruptions of key resources was the top external risk to organisations identified by Chief Risk Officers in a July 2023 World Economic Forum survey after high inflation and interest rates. There is a good chance that this lack of predictability will intensify over the next few years, as geopolitical and security risks – from rising China-US trade tensions to accelerating climate change – weigh more heavily on suppliers, producers and transporters.

Global supply chains will almost certainly bear the cost of geostrategic competition, as the US and some of its allies press technology firms to relocate production and assembly away from China. Such efforts will probably enhance the resilience of some Western economies and global companies. By reducing their dependence on China for critical goods and technologies, for example, the US and some European states will limit their vulnerability to economic coercion and geopolitical shocks. This includes the fallout of a potential crisis in the Taiwan Strait – a scenario which we consider in greater detail within this Strategic Outlook.

But a policy of reducing economic reliance on Beijing and other geopolitical rivals (commonly now referred to simply as 'de-risking’) is unlikely to mitigate the impacts of the most pressing and complex issues facing supply chains. Enduring challenges, including Russia’s effective blockade of Ukrainian ports and low water levels in busy waterways like the Panama Canal, will continue to exert upward pressure on fuel and food prices and sustain global market volatility.

De-risking activities will also probably place strains on global economic resilience and growth, by introducing new supply chain vulnerabilities and costs. The IMF, for example, has warned that the lasting financial impact of trade fragmentation could potentially reach up to 7% of global GDP. This is partly because establishing new manufacturing facilities is expensive and can lead to higher production costs.

Alternative manufacturing destinations also have their own vulnerabilities. Alternatives to China – including India, Indonesia, Mexico and Vietnam – are among the most exposed to climate change impacts. Often they have inadequate infrastructure and governance, and face security challenges that can undermine the smooth functioning of supply chains. Others – such as Bangladesh, which we identify here as having a worsening stability outlook – are at risk of political or economic crises that would create additional challenges, including workforce readiness.

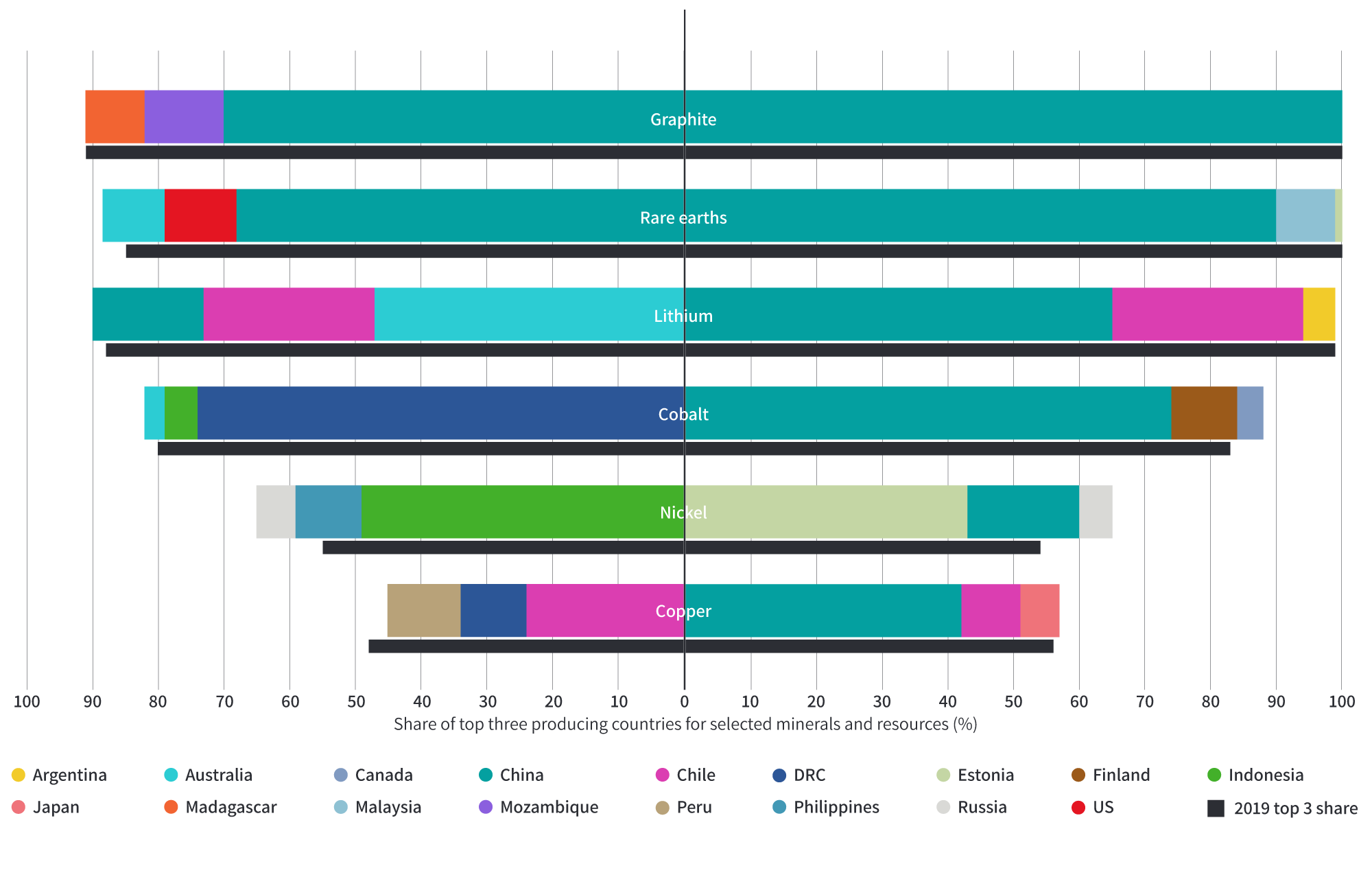

A key risk going forward is how China responds to these efforts to displace it within global supply chains. There seems little doubt that this will include making life more difficult for global businesses that choose to continue operating in China to pressure them and their governments to change course. Beijing will probably also leverage its global dominance within the sectors of extraction and processing of critical minerals.

Reliance on China for supplies of critical minerals will almost certainly remain a strategic vulnerability for many Western economies through 2024 and beyond – given the concentration of resources and refining operations there. Should US-China relations become more fraught, Beijing would probably introduce measures to curb exports – as it did in July 2023 for gallium and germanium. The consequences would be substantial and far-reaching given the criticality of these minerals for most renewable energy technologies and digital devices.

Balancing the benefits of supply chain de-risking with the challenges of diplomacy and managing the vulnerabilities that these activities create will be crucial for achieving more resilient supply chains over the coming years. For those tasked with building resilience, having a clearer understanding of the security trends and risk conditions within a more diverse set of contexts will be important. If strategic risk forecasting does not sit at the centre of supply chain strategy and planning, then resilience may prove both costly and elusive.

A Transient State of Resilience