The war in Ukraine and its repercussions present urgent near-term risks. But the longer-term geopolitical risk of greater consequence remains the deterioration in US-China relations.

Download PDF

Images: Getty Images (Chris McGrath; Yuri Kadobnov; Sam Yeh; Handout)

Seismic events that cause global systematic damage are historically rare, or at least they used to be. The global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic were two shocks of such magnitude that they began to undermine globalisation. The increasing frequency and prevalence of climatic disasters are another such shock. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is also one, but, unlike the rest, it was a wilful blow that also struck the rules-based multilateral order, the nuclear order, the global economy, and the global system of food and energy supply.

Given the global magnitude of its repercussions, the path the Ukraine conflict takes in 2023 will determine many other risks. In Q1, it will probably become clear that Vladimir Putin’s unpopular mobilisation will be insufficient to reverse Russia's fortunes in the war. The question of whether Putin will use a nuclear weapon to forestall a humiliating defeat and political

jeopardy will sustain uncertainty and anxiety. We assess it as an unlikely last resort, and that the war will continue well into 2023. The most probable scenario is that it will become a frozen conflict, giving Putin time to escalate asymmetric pressure on Europe and Ukraine to induce negotiations.

The war in Ukraine and its repercussions present urgent near-term risks. But the longer-term geopolitical risk of greater consequence remains the deterioration in US-China relations. Strategic competition between the two exemplifies the dynamics of this global unravelling. Such competition is arguably the most powerful geopolitical force driving multipolarity in the global order and eroding systems of cooperation and governance that many view as essential to tackle global challenges such as environmental change, food insecurity and inflation.

Lowest

Highest

Difference between 2023 inflation forecast and five-year inflation average

Global inflationary pressure

President Xi Jinping is the only global leader assuredly in office over the coming five years. With a third term now secured, he probably sees less need to resolve the Taiwan question with a high-risk strategy. Instead, we assess that he is more likely to prioritise his goal to make China militarily capable and economically and technologically autonomous and resilient. This will give him greater means to press his claims on Taiwan and in the South and East China Seas more aggressively, probably in a four- to five-year timeframe.

There is considerably less certainty around the leadership of Russia. Most analysis suggests that Putin’s grip on power remains strong and his regime well-proofed against attempts at his removal. But there is a strong historical correlation between failure in wars and irregular or forceful changes in regimes. So it would be imprudent to assume that Russia is not heading towards a political crisis in 2023. For a political system as brittle as Russia’s, that could spell a sudden and rapid unravelling in Russia and its influence around the world.

Perhaps the greatest and most consequential uncertainty though is that of the United States and the outcome of the presidential election in 2024. The outcome of the midterms is unlikely to change medium-term US foreign policy on the key areas of risk. But uncertainty as to who will secure the Republican nomination as well as President Joe Biden’s prospects for continuity as the oldest president in US history will sustain scepticism over how much the US can be relied upon as an ally in the future, and the coherence of its grand strategy.

In this unravelling and volatile global order, the importance of the US as a predictable actor and a reliable partner cannot be understated. But equally, it seems reasonable to anticipate that outside powers will take steps to reduce their security dependencies on the US if they can. And it is unlikely that the few making long-term strategic decisions will risk banking on a full restoration of a US-led global order either. The multipolar order long-foreseen seems to have finally arrived.

Amid all this volatility, much now rests on how governments perform and cooperate to ensure confidence in security guarantees, stabilise global systems, confront global risks, and restore a semblance of order and predictability. And more importantly, a great deal rests on world leaders not taking actions that amplify volatility further due to ideology, incompetence or out of some conception that it will net

them gains.

Leadership will be a central geopolitical risk question hanging over the year in assessing the medium- to longer-term outlook. This is particularly as it pertains to China, Russia and the US, where so much of the outlook rests on the decisions and intentions of these three presidential offices.

Watching the leaders

Russia’s invasion and the risk of conflict in the Taiwan Strait have shown that major interstate war involving superpowers is no longer an unthinkable outlier, nor is the threat of nuclear proliferation and conflict. It would be unwise to assume that a Russian defeat – which is more probable than a decisive victory – would somehow serve as a lesson to others that deters further conflict. Nor would an end to the war bring about a significant near- to medium-term improvement in global security.

This much is clear in the extent to which states from Europe to East Asia plan to spend on defence and reappraise their defence strategies in anticipation of growing insecurity. Inflation levels suggest global defence spending will decline overall in real terms in 2023. But Europe and Asia in particular are likely to see increased spending. This is driven largely by perceived or actual threats posed by China, Russia, North Korea and Iran to global or regional security, or in the case of those states, by the US and its allies.

While it might also seem reasonable to assume that Russia’s nuclear threat will give impetus to nuclear disarmament, the inverse is more likely. The war in Ukraine has shown that nuclear weapons provide a

cover for states to act against non-nuclear powers and deter the direct intervention of allies. China, Pakistan, India and North Korea – and Iran

if efforts to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action fail – are all likely to expand their nuclear capabilities. This will be at a time when

the backchannels of communication to manage associated risks

are unravelling.

All this should make multilateral institutions as a means to reduce such risks all the more valued and important, but again the inverse is more likely. That so many countries – particularly in the global south – initially failed to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provides some measure of how misaligned the multilateral order has become. And it reflects how many states have adopted ambiguous hedging and abstaining postures that allow them to balance relations between strategic competitors, if not appease them out of uncertainty about their own security and stability.

As tensions between the US and China rise, and trust in bodies like the UN Security Council declines, a likely path for many countries seeking security will be regional security pacts and security guarantees under a nuclear umbrella, or neutrality and appeasement. The latter may become the norm if confidence in security guarantees is low.

War and global security

Strategic competition between the US and China has high potential to unleash further global shocks. If the competition is poorly managed, these shocks could turn unravelment into near virtual collapse.

The systems, institutions and orders that have underpinned relative global stability and security for decades are unravelling and taking new forms.

Strategic competition between the US and China also has a high potential to unleash further global shocks. If the competition is poorly managed, these shocks could turn unravelment into near virtual collapse. The Taiwan question is the most critical. That is, if and when China will try to take control of the island by force, whether that would arise because of actions by the US, and whether the US will come to Taiwan’s defence and lead to war.

We assess that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is highly unlikely in 2023 and over the next few years, but that a renewed crisis in the Taiwan Strait is not. With a presidential election due in Taiwan in 2024, a crisis short of an invasion that might enable China to achieve its political goals without war, such as a naval blockade, is increasingly probable towards the end of 2023. Such a crisis would have wide repercussions on global supply chains, sustain inflationary pressures, and drive further

global volatility.

Such an unravelling of the interconnected systems that govern how the world functions – and how governments cooperate to deal with problems – is the definition of global instability. It makes it more likely that governments will operate outside of established rules and norms. It weakens efforts to build common resilience and security. It also creates opportunities for malign actors to exploit vulnerabilities. All this makes adverse events likely to occur more often, with greater intensity and duration, and to have wider knock-on effects.

This global unravelling is a long-term trend. It is driven by political actors who see established systems of governance as incompatible with their interests, and by others who fail to uphold those systems. But it is also a trend that is now accelerating, as the impacts of global shocks exceed what complex systems constructed over the years can withstand. And it is a trend that makes further global shocks all the more probable.

The systems, institutions and orders that have underpinned relative global stability and security for decades are unravelling and taking new forms. Indeed, many or all of the following are in states of flux, degradation or redefinition: globalisation, trade agreements, political systems, ecosystems, climate systems, supply chains, security alliances, systems of influence and patronage, civil rights, the nuclear order and the multilateral global order.

Many of the risks, trends and events that we forecast in Strategic Outlook 2023 can be viewed through this lens of unravelment, and how political and other actors are responding to this. Themes that run through our forecasts this year include regional and geostrategic competition, worsening governance standards, crises caused by climatic events, insecurity of food, water and energy, rising debt and inflation, and deteriorating socio-economic conditions.

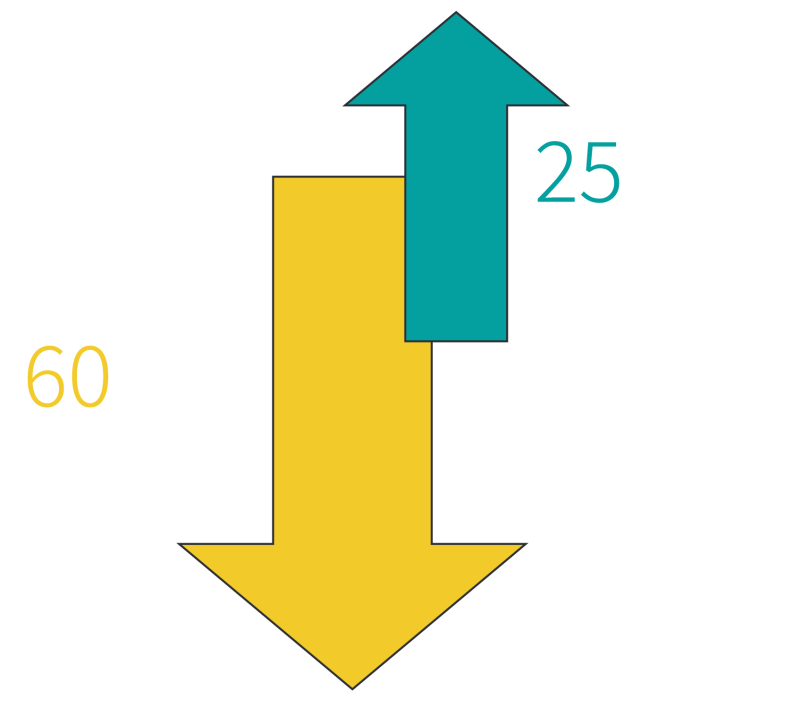

The outlook for 2023 is one of persisting volatility worldwide as the world rapidly adapts to changes and challenges wrought by war, great power competition, and economic turmoil. At a headline level, we assess that 99 countries have a worsening outlook compared with 29 that are likely to see improvement. The outlook for the remainder is consistent with 2022, but given the events of the past year, this broadly means a continuum of uncertainty.

Unravelling