Major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile face significant challenges in the year ahead, and we forecast that

all three will experience

political or electoral crises

and related unrest.

& Caribbean

A long road to recovery

Latin America & Caribbean

GROUPS TO WATCH

➝ CGT, CTA and ATE unions

➝ La Campora and Movimiento Evita

➝ CRA, CCC and CTEP

➝ MPR Quebracho

➝ Polo Obrero and Barrios de Pie

➝ Frente Popular Dario Santillan

➝ UTEP, MST and MTL

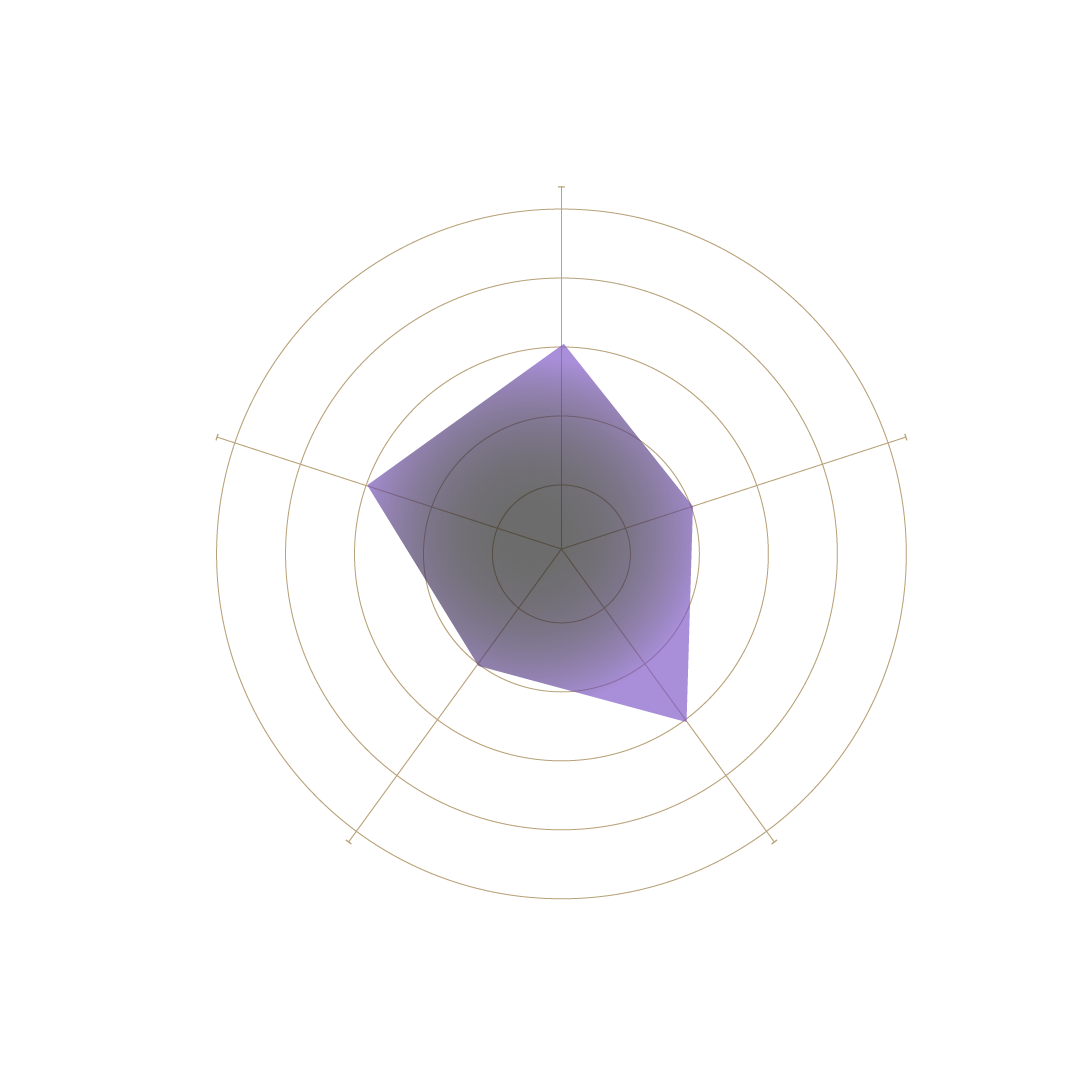

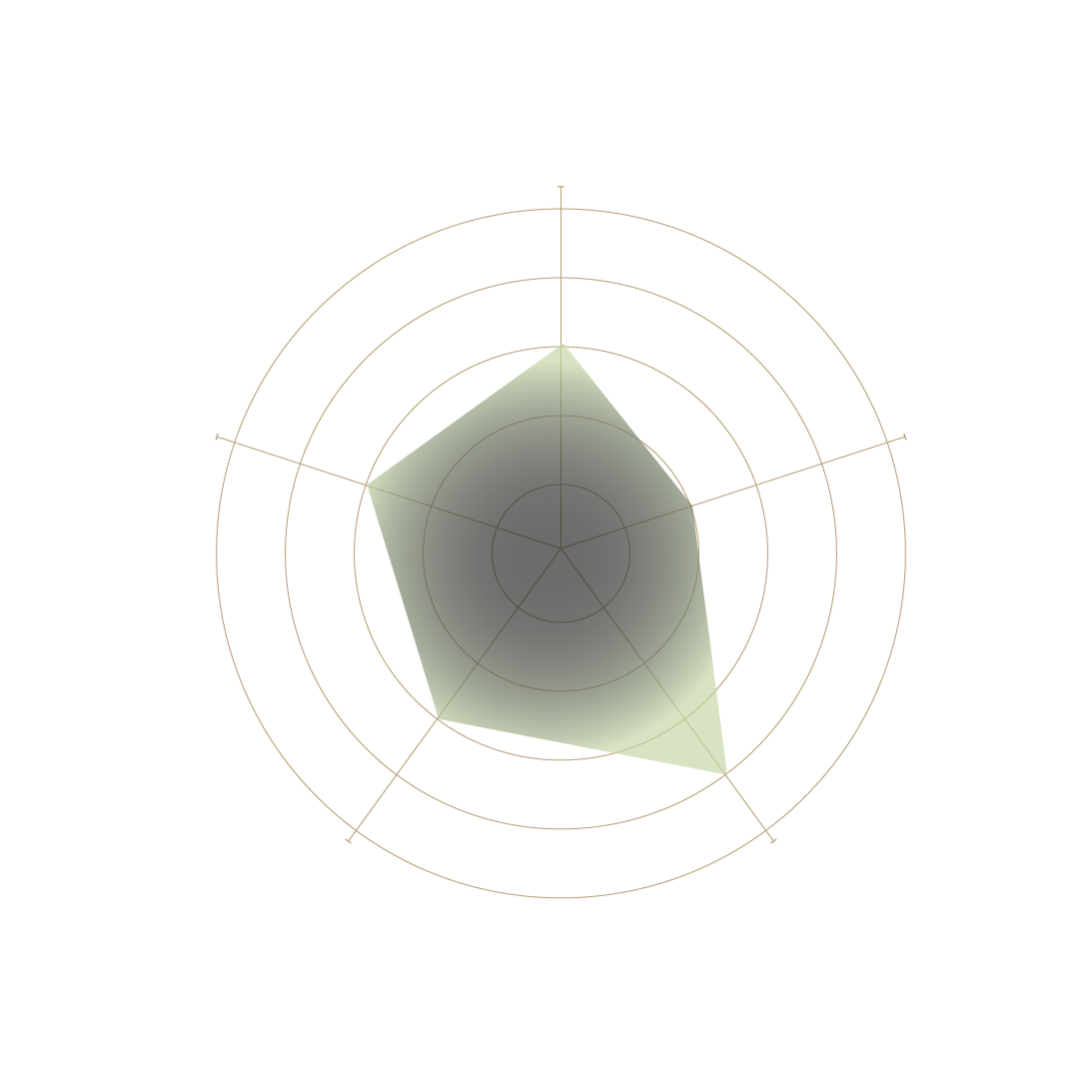

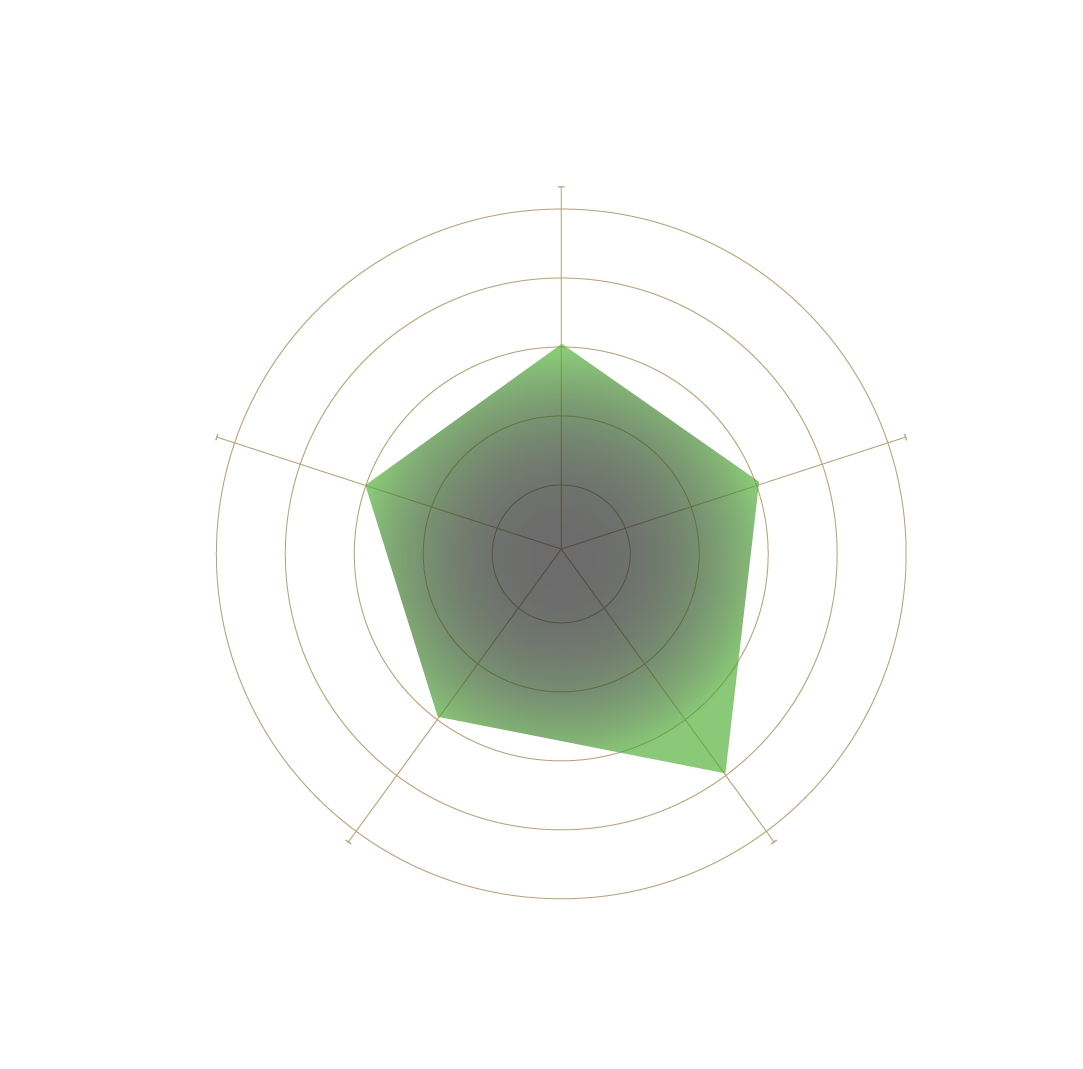

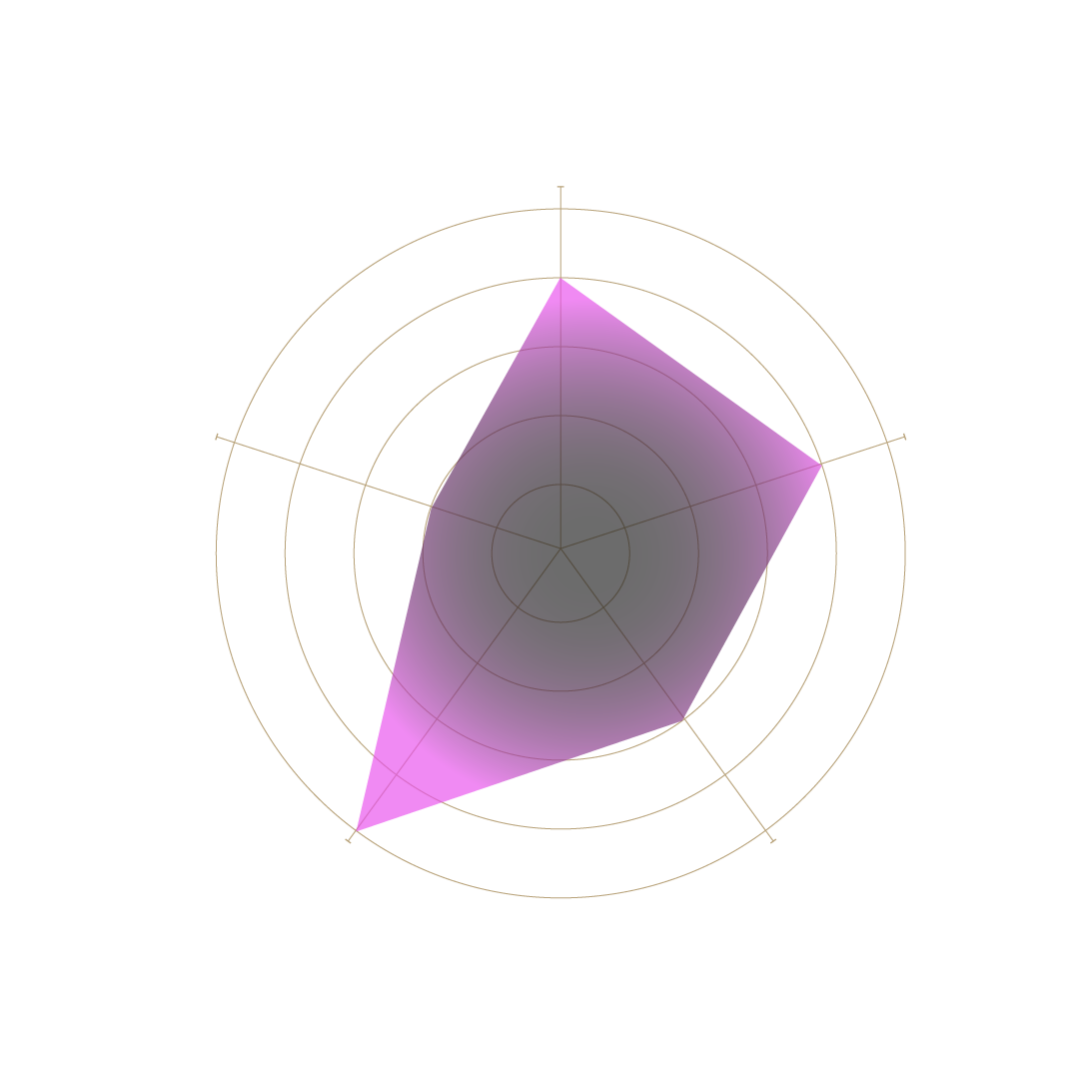

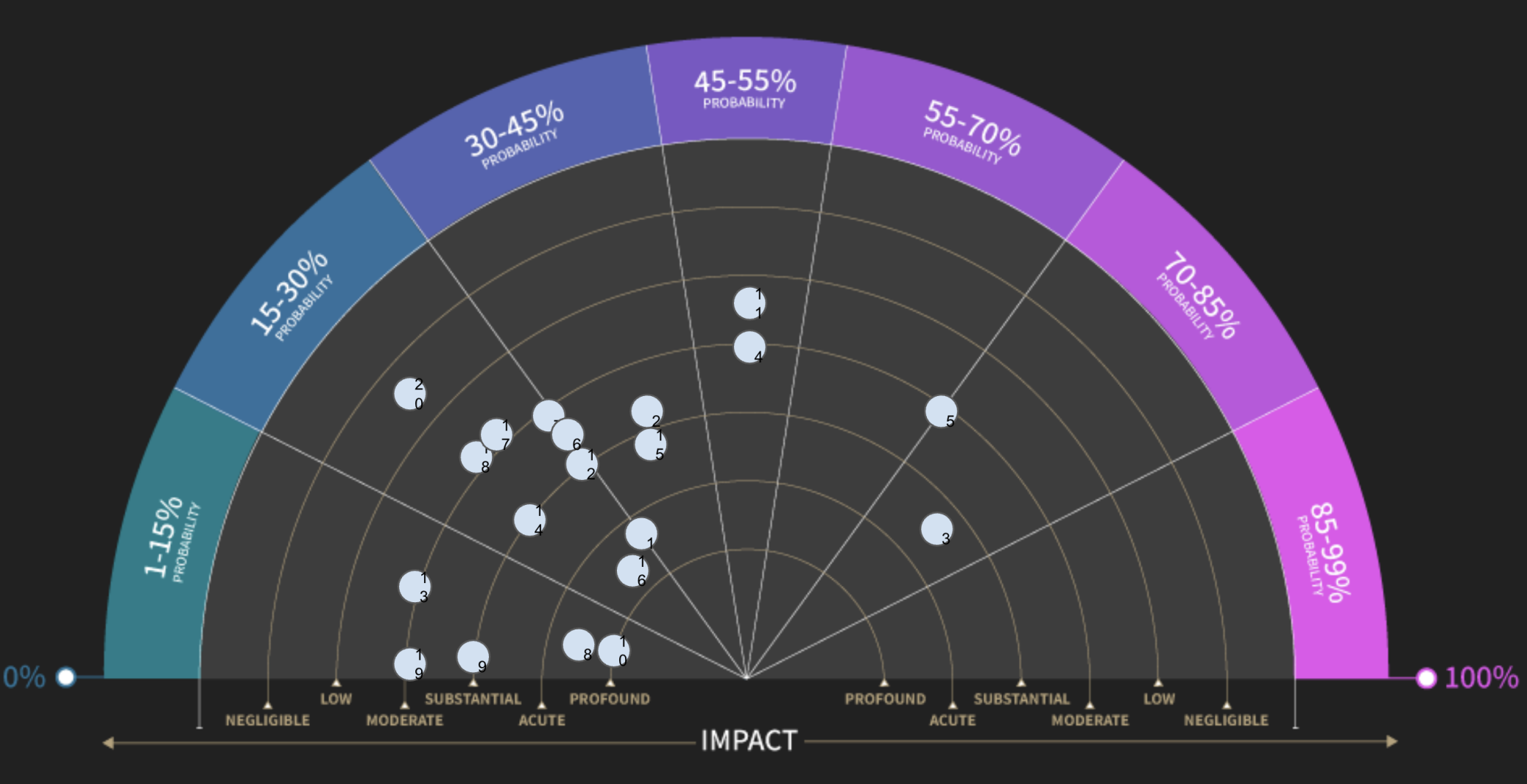

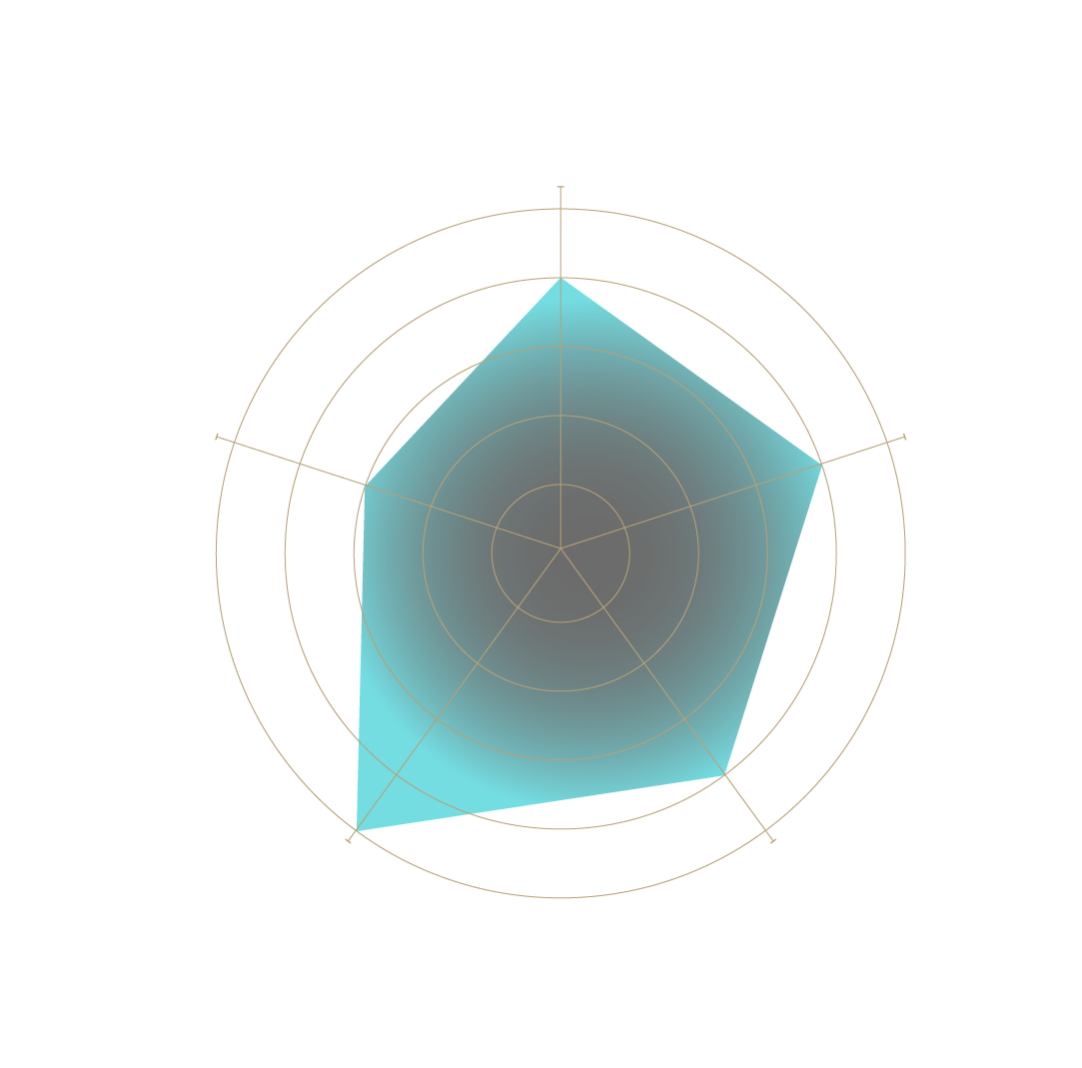

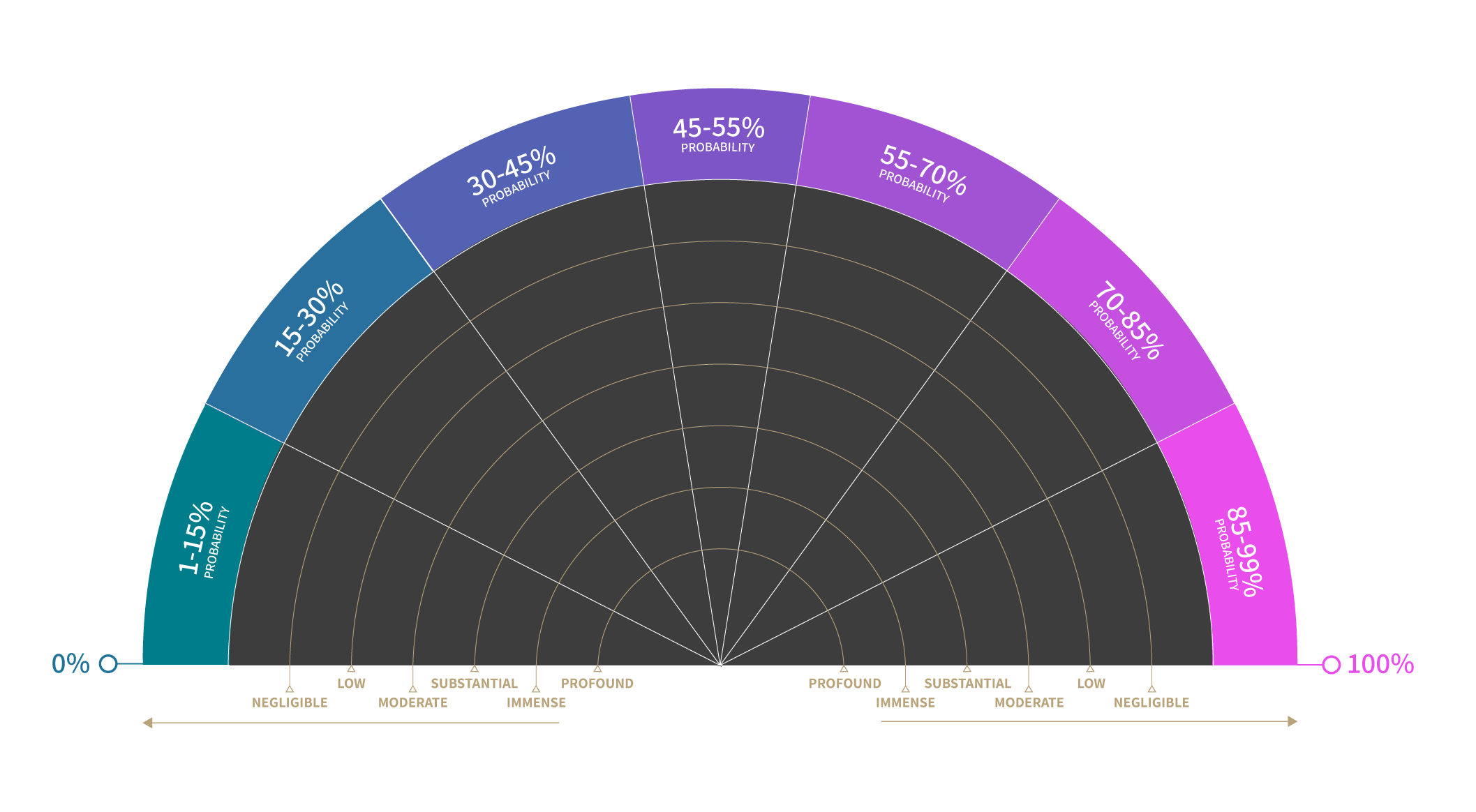

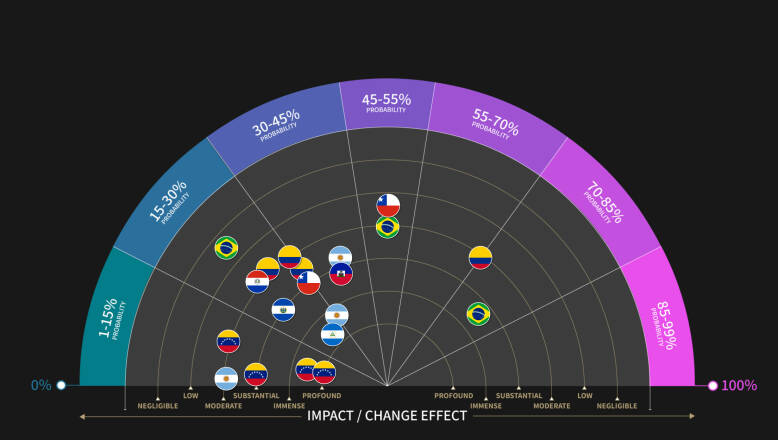

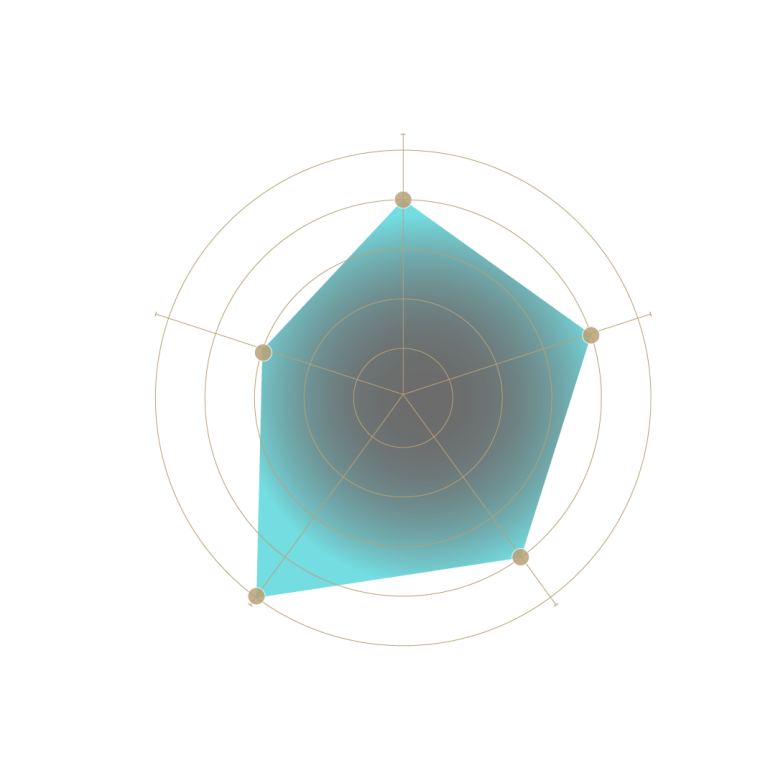

The Covid-19 pandemic hit Latin American economies harder than probably any other region. Going into 2022, major economies there, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile, still face a rocky road. This will sustain a high potential for political or electoral crises and related unrest throughout the coming year. The charts show our judgments of the intensity of five indicators for protests and unrest in Latin America in 2022.

TRIGGERS TO WATCH

➝ Negotiations with the IMF

➝ Covid-19-related restrictions

➝ Economic measures social movements

perceive as right-wing

➝ Further restrictions on exports

➝ Restrictions on access to foreign currency

Ripe for revolt

Peru

Colombia

Chile

Brazil

Argentina

CLICK ON POINTS

TO REVEAL INFO

CLICK ON FLAGS TO

SHOW INFORMATION

Forecasts

Dates to watch

Key indicators

Government spending cuts

Efforts by governments across Latin America to reduce expenditures in 2022 to service debt taken on during the Covid-19 pandemic will be a key early-warning indicator that civil unrest or political crisis is likely. With the economic outlook still bleak for many people across the region, such efforts would almost certainly sustain popular grievances with governments. Any policies that activists and trade unions in particular perceive as disproportionately impacting low-income citizens are probable triggers for periods of economic and political tumult, particularly in Argentina, Brazil and to a lesser extent Chile and Colombia.

Relations between Argentina and its foreign debtors

The Argentine government’s relationship with its foreign debtors, particularly the IMF, will be a determining factor in its ability to avoid a political or economic crisis in 2022. Failure to renegotiate its repayments to the IMF would portend another default on its international debts, at the very least compounding the country’s economic malaise and sustaining public disaffection with the government. It would also probably prompt a run on the Argentine peso and force the authorities into restricting access to foreign currency.

President Bolsonaro and his base

The degree to which President Bolsonaro maintains influence over his supporters is likely to determine the likelihood and severity of any crisis around the 2022 presidential election. So far, his supporters have followed the president’s lead in questioning the legitimacy of the poll. But efforts by his hardcore activists to mount protests or strikes that the president does not organise himself or has openly criticised would signal that his control over his backers is waning. These would point to a high likelihood of violent protests or attacks against government buildings if Mr Bolsonaro loses the election.

Chile

Day of the Young Combattant

29 March

Cuba / Jamaica

Rainy season

May

Costa Rica

Rainy season

May–November

Carribean

End of Ramadan

1 May

Latin America

Earth Day

22 April

Carribean

Earth Day

22 April

Latin America

Start of Ramadan

2 April

Carribean

Start of Ramadan

2 April

Chile / Colombia

Rainy season

April–May

Argentina

Anniversary of 1976 military coup

24 March

Latin America

End of Ramadan

1 May

Latin America

Annunciation Day

25 March

Colombia

General election

13 March

Carribean

Annunciation Day

25 March

Caribbean

Caribbean Community Summit

23 February–24 February

Caribbean

Caribbean Community Summit

23 February–24 February

Costa Rica

General election

6 February

Latin America

Orthodox Christmas Eve

6 January

Carribean

Orthodox Christmas Eve

6 January

Peru

Rainy season

January–April

Mexico

Rainy season

May–October

Latin America

Eid Al-Fitr

2 May–3 May

Chile

Anniversary of 1973 military coup

11 September

Brazil

Rainy season in northern Brazil

December–March

Latin AmericA

MERCOSUR summit

Before December

Chile

Anniversary of 2018 Mapuche community member assassination

14 November

Bolivia

Rainy season

November–March

Chile

Anniversary of beginning of 2019 anti-government unrest

18 October

Mexico

Anniversary of 1968 Tlateloco massacre

2 October

Brazil

General election

2 October

Colombia

Rainy season

October–November

Mexico

Anniversary of 2014 Ayotzinapa students disappearance

26 September

Cuba / Jamaica

Rainy season

September–November

Carribean

Eid Al-Fitr

2 May–3 May

Latin America

Ashura

7 August–8 August

Carribean

Ashura

7 August–8 August

Argentina

Anniversary of 2017 disappearance of Mapuche activist

1 August

Latin America

Eid Al-Adha

9 July

Chile

Anniversary of 2020 killing of a Mapuche militant

9 July

Carribean

Eid Al-Adha

9 July

Argentina

Rainy season

June–August

Caribbean

Hurricane season

June - November

COLOMBIA

Presidential election

29 May

Cuba

Anniversary of the Cuban revolution

1 January

Scroll down

A long road

to recovery

Political and economic stability, and consequently security, are all likely to deteriorate in Latin America in 2022. Major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile face significant challenges in the year ahead, and we forecast that all three will experience political or electoral crises and related unrest that will slow growth and negatively impact many other countries in the region.

Widespread public anger over hardships and inequality, insecurity, polarising politics, corruption and weakening democratic governance present strategic risks to a region that looks likely to be left behind in the global economic recovery.

The Covid-19 pandemic has hit Latin America harder than probably any other region, accounting for around a third of deaths globally despite having only eight percent of the global population. The IMF has forecast that per capita income for the region will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2025. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), a UN body, has forecast that economies in the region will not snap back from the contractions experienced in 2020 until at least 2022.

The reasons for Latin America’s almost unmatched vulnerabilities to the pandemic are many, and point to why the outlook we foresee is so negative. These include inadequate investment in healthcare, public services and social welfare; large informal economies; poor governance standards and corruption; and above all, deep social and economic inequalities. All these factors are liable to keep the region stuck in economic stagnation and underperformance in 2022. The widespread prevalences of violent and organised crime and social unrest are all likely to persist through 2022, marking an unstable and slow recovery.

The public desires and expectations for deep political reform to change this outlook are widespread. But the prospects of these structural weaknesses being redressed in 2022 are slim. Realistically, only Uruguay gives much cause for optimism, although elections in Brazil and Colombia are important to watch as potential and more positive turning points. Nevertheless, the required level of consensus and competence in governance to implement reforms is likely to prove a challenge for many of the region's politicians. The headwinds of fiscal pressures, political polarisation, populism and corruption in particular suggest that any attempts at political change are more likely than not to be destabilising in the near term. >>

Images: Getty Images (Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP; Claudio Reyes/AFP; Ricardo Vallejo / Eyeem; Juan Mabromata; Andressa Anholete)

Risk dashboard

Infographic

Assessment

Forecasts

Dates to watch

Key indicators

A long road to recovery

Major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile face significant challenges in the year ahead, and we forecast that

all three will experience

political or electoral crises

and related unrest.

America

For best results

We recommend that you view this in a desktop browser. If using a tablet or smartphone, some infographics may only respond to device-specific gestures.

Forecasts

The Covid-19 pandemic hit Latin American economies harder than probably any other region. Going into 2022, major economies there, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile, still face a rocky road. This will sustain a high potential for political or electoral crises and related unrest throughout the coming year. The charts show our judgments of the intensity of five indicators for protests and unrest in Latin America in 2022.

Images: Getty Images (Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP; Claudio Reyes/AFP; Ricardo Vallejo / Eyeem; Juan Mabromata; Andressa Anholete)

Key indicators

Government spending cuts

Efforts by governments across Latin America to reduce expenditures in 2022 to service debt taken on during the Covid-19 pandemic will be a key early-warning indicator that civil unrest or political crisis is likely. With the economic outlook still bleak for many people across the region, such efforts would almost certainly sustain popular grievances with governments. Any policies that activists and trade unions in particular perceive as disproportionately impacting low-income citizens are probable triggers for periods of economic and political tumult, particularly in Argentina, Brazil and to a lesser extent Chile and Colombia.

Relations between Argentina and its foreign debtors

The Argentine government’s relationship with its foreign debtors, particularly the IMF, will be a determining factor in its ability to avoid a political or economic crisis in 2022. Failure to renegotiate its repayments to the IMF would portend another default on its international debts, at the very least compounding the country’s economic malaise and sustaining public disaffection with the government. It would also probably prompt a run on the Argentine peso and force the authorities into restricting access to foreign currency.

President Bolsonaro and his base

The degree to which President Bolsonaro maintains influence over his supporters is likely to determine the likelihood and severity of any crisis around the 2022 presidential election. So far, his supporters have followed the president’s lead in questioning the legitimacy of the poll. But efforts by his hardcore activists to mount protests or strikes that the president does not organise himself or has openly criticised would signal that his control over his backers is waning. These would point to a high likelihood of violent protests or attacks against government buildings if Mr Bolsonaro loses the election.

Brazil

Rainy season in northern Brazil

December–March

Chile

Day of the Young Combattant

29 March

Cuba / Jamaica

Rainy season

May

Costa Rica

Rainy season

May–November

Carribean

End of Ramadan

1 May

Latin America

Earth Day

22 April

Carribean

Earth Day

22 April

Latin America

Start of Ramadan

2 April

Carribean

Start of Ramadan

2 April

Chile / Colombia

Rainy season

April–May

Argentina

Anniversary of 1976 military coup

24 March

Latin America

End of Ramadan

1 May

Latin America

Annunciation Day

25 March

Colombia

Annunciation Day

13 March

Carribean

Annunciation Day

25 March

Caribbean

Caribbean Community Summit

23 February–24 February

Caribbean

Caribbean Community Summit

23 February–24 February

Costa Rica

General election

6 February

Latin America

Orthodox Christmas Eve

6 January

Carribean

Orthodox Christmas Eve

6 January

Peru

Rainy season

January–April

Mexico

Rainy season

May - September

Latin America

Eid Al-Fitr

2 May–3 May

Latin AmericA

MERCOSUR summit

Before December

Brazil

General election

2 October

Carribean

Eid Al-Adha

9 July

Cuba / Jamaica

Rainy season

September–November

Bolivia

Rainy season

November–March

Chile

Anniversary of 2018 Mapuche community member assassination

14 November

Chile

Anniversary of beginning of 2019 anti-government unrest

18 October

Mexico

Anniversary of 1968 Tlateloco massacre

2 October

Colombia

Rainy season

October–November

Carribean

Eid Al-Fitr

2 May - 3 May

Mexico

Anniversary of 2014 Ayotzinapa students disappearance

26 September

Chile

Anniversary of 1973 military coup

11 September

Latin America

Ashura

7 August–8 August

Carribean

Ashura

7 August–8 August

Argentina

Anniversary of 2017 disappearance of Mapuche activist

1 August

Latin America

Eid Al-Adha

9 July

Chile

Anniversary of 2020 killing of a Mapuche militant

9 July

Argentina

Rainy season

June–August

Caribbean

Hurricane season

June - November

COLOMBIA

Presidential election

29 May

Cuba

Anniversary of the Cuban revolution

1 January

A long road

to recovery

Political and economic stability, and consequently security, are all likely to deteriorate in Latin America in 2022. Major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile face significant challenges in the year ahead, and we forecast that all three will experience political or electoral crises and related unrest that will slow growth and negatively impact many other countries in the region.

Widespread public anger over hardships and inequality, insecurity, polarising politics, corruption and weakening democratic governance present strategic risks to a region that looks likely to be left behind in the global economic recovery.

The Covid-19 pandemic has hit Latin America harder than probably any other region, accounting for around a third of deaths globally despite having only eight percent of the global population. The IMF has forecast that per capita income for the region will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2025. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), a UN body, has forecast that economies in the region will not snap back from the contractions experienced in 2020 until at least 2022.

The reasons for Latin America’s almost unmatched vulnerabilities to the pandemic are many, and point to why the outlook we foresee is so negative. These include inadequate investment in healthcare, public services and social welfare; large informal economies; poor governance standards and corruption; and above all, deep social and economic inequalities. All these factors are liable to keep the region stuck in economic stagnation and underperformance in 2022. The widespread prevalences of violent and organised crime and social unrest are all likely to persist through 2022, marking an unstable and slow recovery.

The public desires and expectations for deep political reform to change this outlook are widespread. But the prospects of these structural weaknesses being redressed in 2022 are slim. Realistically, only Uruguay gives much cause for optimism, although elections in Brazil and Colombia are important to watch as potential and more positive turning points. Nevertheless, the required level of consensus and competence in governance to implement reforms is likely to prove a challenge for many of the region's politicians. The headwinds of fiscal pressures, political polarisation, populism and corruption in particular suggest that any attempts at political change are more likely than not to be destabilising in the near term. >>