Images: Getty Images (Vizzor Image; Ronaldo Schemidt)

Scroll down

This poor economic outlook in Latin America gives the US a chance to counter and stay ahead of Chinese influence in the region and reassert its standing.

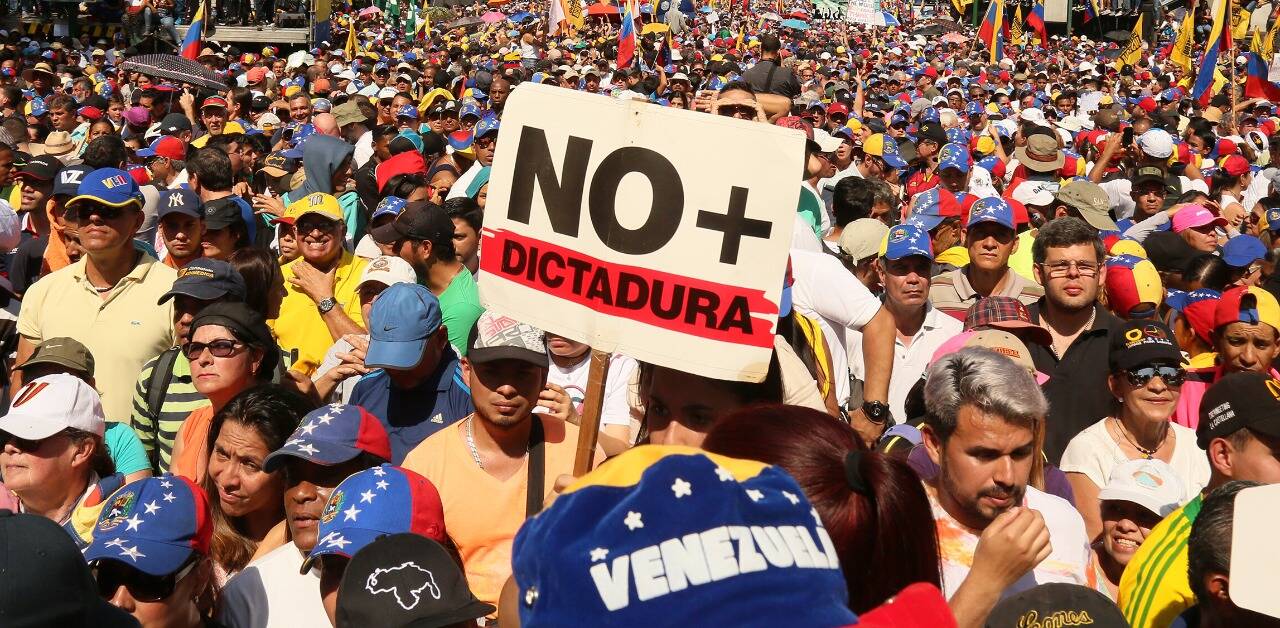

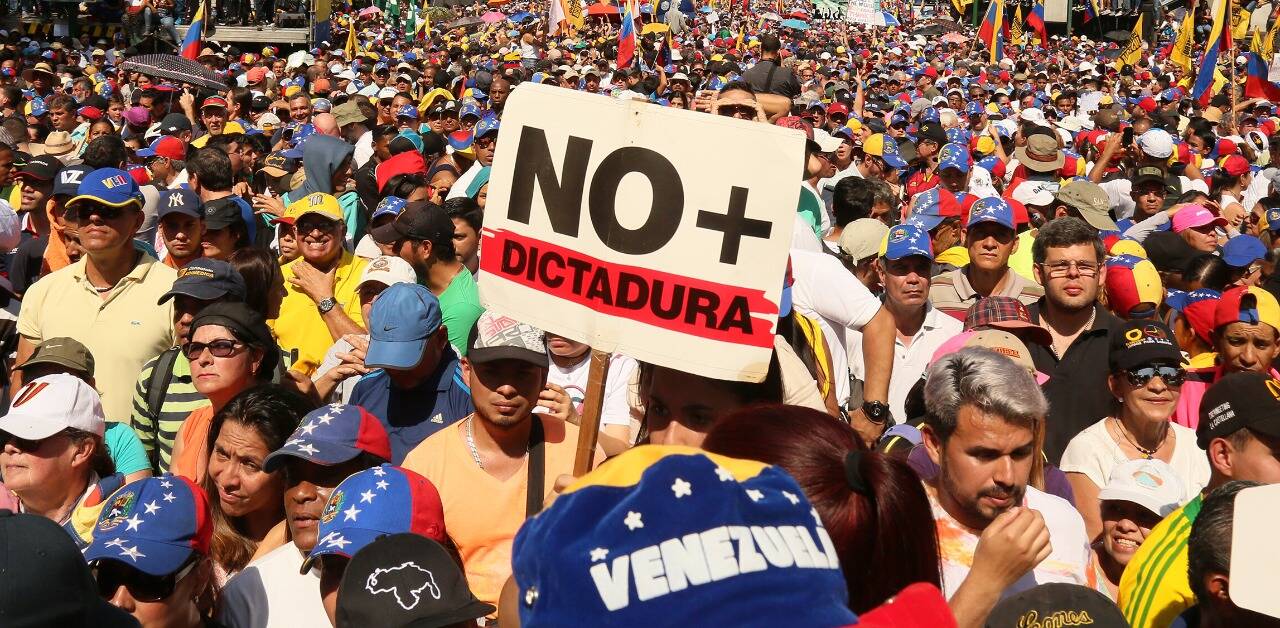

The rising financial pressures on the Argentine government will also hinder it as it tries to placate an increasingly frustrated population. The Peronist governing party’s poor performance in the primary polls for legislative elections on 14 November is one sign that public patience is waning. As living standards worsen in the coming months, particularly in the event of a debt default, we forecast that already-common large-scale protests will become yet more frequent and the risk of civil disorder and crime will rise. This is particularly a risk in and around Buenos Aires.

A period of violent demonstrations and unrest in Argentina would probably not result in the resignation of President Alberto Fernandez. This is not least because most opposition parties would probably rather cooperate with a weakened president than see his vice president, former president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, assume his position. Still, such socio-economic pressures would probably evolve into a long-lasting political paralysis, consumed by infighting and result in a split in the governing party, with Vice President Kirchner’s party emerging as a particular challenge.

An unsettled political outlook also looks very likely to impact Brazil in 2022, where we forecast a difficult electoral period and change of government yielding a period of uncertainty in governance. A general election is due in October and President Bolsonaro is unlikely to win re-election. But he is setting the stage for a contentious campaign and a period of political uncertainty is likely to run through the year and follow into 2023 as opposing sides refuse to accept the legitimacy of whatever outcome arises.

In some ways, Mr Bolsonaro seems to be following the strategy that former US president Donald Trump used ahead of the 2020 US election, by trying to undermine the legitimacy of the process, and so preparing his supporters to reject the results. We anticipate that the president will make increasingly vocal and inflammatory allegations of fraud and rigging against the electoral commission in the coming months. Violence by some of his more-extreme supporters is a probable outcome throughout and beyond this electoral period.

Although he has not formally announced his candidacy, we forecast that former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva will probably run and win the presidential election in Brazil. Mr Bolsonaro’s handling of the pandemic has damaged his public standing. Alongside the impact of potentially inflammatory narratives from Bolsonaro’s campaign, and the social division that his presidency has exacerbated over the past three years, we anticipate that a win for the leftist candidate Mr Lula would prompt a brief period of violent protests in Q4. Resulting political uncertainty as Mr Bolsonaro challenges the legality of the results is also likely to act as a drag on Brazil’s economic recovery going into 2023.

The democratic and constitutional institutions of Brazil are probably strong enough to withstand such an electoral crisis. But there is likely to be significant pressure on the electoral commission and judiciary to stand up to challenges against the result. Indeed, such pressure on the integrity of Brazil’s institutions may prove an important measure of how lasting the impacts of Mr Bolsonaro’s populist authoritarianism are going to be on Brazilian democracy.

We anticipate acts of vandalism and propaganda campaigns against these institutions in a bid to influence and undermine them to suit partisan agendas. Perceived left-leaning politicians and media outlets will also potentially be subject to harassment and threats of violence. This is both in the lead-up to the election as well as after, particularly around the announcement of results and any subsequent legal challenge from Mr Bolsonaro.

The probable economic downturns and political instability in the region’s two largest economies, Argentina and Brazil, would have repercussions elsewhere. Chile and Colombia are two countries that we forecast will be vulnerable to social upheaval, due to their efforts to limit public spending and boost government revenues. Their domestic economies have already been hit hard by the pandemic as well as trade union-led industrial action and protests. Such events have proven a challenge for managing security risks in these two countries over the past three years, and 2022 is unlikely to be any different.

We do not anticipate such socio-economic difficulties in Chile or Colombia to lead to the sort of political crises that we forecast in Argentina or Brazil. But both are vulnerable to periods of economic and political tumult, and a confluence of several foreseeable events in 2022 could prove destabilising and impact security and confidence.

For Chile, the main issue to watch is a plebiscite on constitutional changes with an outlier scenario that the military will muscle in on the political process. For Colombia, a reversion to a violent response from the authorities to recurring anti-government protests would probably intensify the campaign and lead to greater pressure on the government to step down. But given that this was the trigger for a prolonged period of unrest in April-June 2021, police are likely to have a more measured response to any new protests.

Despite the many pressures on countries in Latin America, major crises of a magnitude that would make doing business no longer viable are less than likely in most countries. But periods of civil unrest, and temporary breakdowns in law and order, particularly in deprived urban areas, remain likely in the region in 2022. The negative events we foresee as being likely will also play an important role in a longer-term negative trend in the region more broadly. This is a gradual weakening of governance standards and faltering public confidence in the state. Such a decline threatens to make even major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Colombia more vulnerable to major crises in the future. The region can ill-afford any of its leading governments to fail in 2022.

The IMF has said it expects Latin America to lag more than a percentage point behind other emerging markets in its post-pandemic recovery.

This poor economic outlook in Latin America gives the US a chance to counter and stay ahead of Chinese influence in the region and reassert its standing. This is an opportunity we forecast that the Biden Administration will very likely prioritise and pursue in 2022, given its wider challenges competing with China in other regions. But the extent to which this will reduce the likelihood and impact of the economic and political risks we forecast in 2022 will almost certainly be limited, although it may forestall the worst case scenarios.

Most financial assistance to the region during the pandemic has come from US-headquartered intergovernmental organisations, Western lenders, and the US itself. While the US has donated close to 40m Covid-19 vaccines to Latin America, China has given fewer than a million. Biden administration officials have conducted meetings with Latin American leaders, businesses and civil society as part of plans for its Build Back Better World, which portends an increase in investment in infrastructure projects in the coming years. Such initiatives look particularly likely in Colombia, Ecuador and Panama.

Nevertheless, China will remain an attractive source of investment and loans for several Latin American countries, especially given that Beijing’s engagement comes with relatively few conditions. We forecast that the northern triangle countries of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) will remain particularly susceptible to Chinese investment. This is not least because their leaders are unsurprisingly resistant to Washington’s efforts to tackle political corruption in these countries.

Moves to improve diplomatic relations with Beijing at the expense of those with Washington would portend a further degradation of governance standards, provide succour to corruption, and set back efforts to stem authoritarianism. The post-Covid-19 recovery and sense of another wave of crises could, conversely, spark a political regeneration in a region that has fallen far short of its potential in recent years. The many headwinds suggest that is too optimistic to expect in 2022.◼

This poor economic outlook in Latin America gives the US a chance to counter and stay ahead of Chinese influence in the region and reassert its standing. This is an opportunity we forecast that the Biden Administration will very likely prioritise and pursue in 2022, given its wider challenges competing with China in other regions. But the extent to which this will reduce the likelihood and impact of the economic and political risks we forecast in 2022 will almost certainly be limited, although it may forestall the worst case scenarios.

Most financial assistance to the region during the pandemic has come from US-headquartered intergovernmental organisations, Western lenders, and the US itself. While the US has donated close to 40m Covid-19 vaccines to Latin America, China has given fewer than a million. Biden administration officials have conducted meetings with Latin American leaders, businesses and civil society as part of plans for its Build Back Better World, which portends an increase in investment in infrastructure projects in the coming years. Such initiatives look particularly likely in Colombia, Ecuador and Panama.

Nevertheless, China will remain an attractive source of investment and loans for several Latin American countries, especially given that Beijing’s engagement comes with relatively few conditions. We forecast that the northern triangle countries of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) will remain particularly susceptible to Chinese investment. This is not least because their leaders are unsurprisingly resistant to Washington’s efforts to tackle political corruption in these countries.

Moves to improve diplomatic relations with Beijing at the expense of those with Washington would portend a further degradation of governance standards, provide succour to corruption, and set back efforts to stem authoritarianism. The post-Covid-19 recovery and sense of another wave of crises could, conversely, spark a political regeneration in a region that has fallen far short of its potential in recent years. The many headwinds suggest that is too optimistic to expect in 2022.◼

This poor economic outlook in Latin America gives the US a chance to counter and stay ahead of Chinese influence in the region and reassert its standing.

The IMF has said it expects Latin America to lag more than a percentage point behind other emerging markets in its post-pandemic recovery.

The probable economic downturns and political instability in the region’s two largest economies, Argentina and Brazil, would have repercussions elsewhere. Chile and Colombia are two countries that we forecast will be vulnerable to social upheaval, due to their efforts to limit public spending and boost government revenues. Their domestic economies have already been hit hard by the pandemic as well as trade union-led industrial action and protests. Such events have proven a challenge for managing security risks in these two countries over the past three years, and 2022 is unlikely to be any different.

We do not anticipate such socio-economic difficulties in Chile or Colombia to lead to the sort of political crises that we forecast in Argentina or Brazil. But both are vulnerable to periods of economic and political tumult, and a confluence of several foreseeable events in 2022 could prove destabilising and impact security and confidence.

For Chile, the main issue to watch is a plebiscite on constitutional changes with an outlier scenario that the military will muscle in on the political process. For Colombia, a reversion to a violent response from the authorities to recurring anti-government protests would probably intensify the campaign and lead to greater pressure on the government to step down. But given that this was the trigger for a prolonged period of unrest in April-June 2021, police are likely to have a more measured response to any new protests.

Despite the many pressures on countries in Latin America, major crises of a magnitude that would make doing business no longer viable are less than likely in most countries. But periods of civil unrest, and temporary breakdowns in law and order, particularly in deprived urban areas, remain likely in the region in 2022. The negative events we foresee as being likely will also play an important role in a longer-term negative trend in the region more broadly. This is a gradual weakening of governance standards and faltering public confidence in the state. Such a decline threatens to make even major economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Colombia more vulnerable to major crises in the future. The region can ill-afford any of its leading governments to fail in 2022.

The rising financial pressures on the Argentine government will also hinder it as it tries to placate an increasingly frustrated population. The Peronist governing party’s poor performance in the primary polls for legislative elections on 14 November is one sign that public patience is waning. As living standards worsen in the coming months, particularly in the event of a debt default, we forecast that already-common large-scale protests will become yet more frequent and the risk of civil disorder and crime will rise. This is particularly a risk in and around Buenos Aires.

A period of violent demonstrations and unrest in Argentina would probably not result in the resignation of President Alberto Fernandez. This is not least because most opposition parties would probably rather cooperate with a weakened president than see his vice president, former president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, assume his position. Still, such socio-economic pressures would probably evolve into a long-lasting political paralysis, consumed by infighting and result in a split in the governing party, with Vice President Kirchner’s party emerging as a particular challenge.

An unsettled political outlook also looks very likely to impact Brazil in 2022, where we forecast a difficult electoral period and change of government yielding a period of uncertainty in governance. A general election is due in October and President Bolsonaro is unlikely to win re-election. But he is setting the stage for a contentious campaign and a period of political uncertainty is likely to run through the year and follow into 2023 as opposing sides refuse to accept the legitimacy of whatever outcome arises.

In some ways, Mr Bolsonaro seems to be following the strategy that former US president Donald Trump used ahead of the 2020 US election, by trying to undermine the legitimacy of the process, and so preparing his supporters to reject the results. We anticipate that the president will make increasingly vocal and inflammatory allegations of fraud and rigging against the electoral commission in the coming months. Violence by some of his more-extreme supporters is a probable outcome throughout and beyond this electoral period.

Although he has not formally announced his candidacy, we forecast that former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva will probably run and win the presidential election in Brazil. Mr Bolsonaro’s handling of the pandemic has damaged his public standing. Alongside the impact of potentially inflammatory narratives from Bolsonaro’s campaign, and the social division that his presidency has exacerbated over the past three years, we anticipate that a win for the leftist candidate Mr Lula would prompt a brief period of violent protests in Q4. Resulting political uncertainty as Mr Bolsonaro challenges the legality of the results is also likely to act as a drag on Brazil’s economic recovery going into 2023.

The democratic and constitutional institutions of Brazil are probably strong enough to withstand such an electoral crisis. But there is likely to be significant pressure on the electoral commission and judiciary to stand up to challenges against the result. Indeed, such pressure on the integrity of Brazil’s institutions may prove an important measure of how lasting the impacts of Mr Bolsonaro’s populist authoritarianism are going to be on Brazilian democracy.

We anticipate acts of vandalism and propaganda campaigns against these institutions in a bid to influence and undermine them to suit partisan agendas. Perceived left-leaning politicians and media outlets will also potentially be subject to harassment and threats of violence. This is both in the lead-up to the election as well as after, particularly around the announcement of results and any subsequent legal challenge from Mr Bolsonaro.